Virgin and Child by Jos van Cleve is an oil painting on a wood panel that belongs to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. The work was recently restored in preparation for the upcoming exhibition Madonnas and Miracles. The painting was in excellent condition prior to the conservation treatment, apart from a discoloured varnish that obscured the surface and dulled the vibrant colours used by the artist.

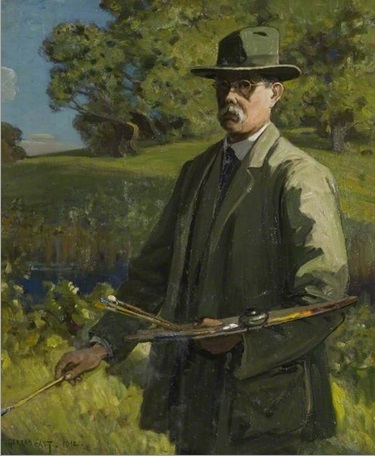

The Artist

Joos van Cleve (1464-1540) was a German-born painter active in Antwerp during the first half of the 16th century. His style can be described as a mixture of traditional Flemish and Italian Renaissance techniques. This particular painting, created between 1525-1529, is a good example of his hybrid style, as the traditional Flemish paint build-up and landscape contrasts with the Virgin’s sfumato shadows copied from paintings by Leonardo da Vinci. The subject of the Virgin and Child was very popular during this period and numerous versions of this composition exist by Joos van Cleve and his studio. The Fitzwilliam version has a peculiar detail, namely that the Virgin is smiling and her teeth are visible between her lips; a feature not usually seen in other representations of the subject.

(click to enlarge photos)

The painting: construction and layers

The wooden support consists of two oak boards, quarter sawn and butt-joined using animal glue. The boards have not separated since the panel’s creation, demonstrating the high quality of the wood and the expertise of the panel makers. We know that the panel had an original engaged frame, since a raised edge or ‘barb’ can be seen along the edge of the white chalk ground. This indicates that the panel was inserted into a frame immediately after its construction. Following this, the ground layer would have been added to the panel and the front of the frame simultaneously, leaving a build-up of ground along the inside of the frame.

A Flemish panel painting of this period would typically have been sized with a layer of animal glue on both sides, in order to limit the hygroscopic response of the wood. Following this, a ground layer would have been applied to the front of the panel in 1-2 layers and sanded to obtain a smooth finish. Northern grounds from the 15th-16th centuries are characterised by their use of animal glue and chalk (calcium carbonate), in contrast to the gypsum (calcium sulphate) grounds used by Italian artists during this period. The preparation of the ground was most likely carried out by professional panel makers, as opposed to the artist’s own workshop. Upon receiving the prepared panel, the artist would start by isolating the ground with a layer of oil (usually linseed or walnut). An initial design of the composition would then be drawn on top of the ground using a dry medium such as charcoal, pencil or chalk. In other cases wet media such as ink or diluted paint were used.

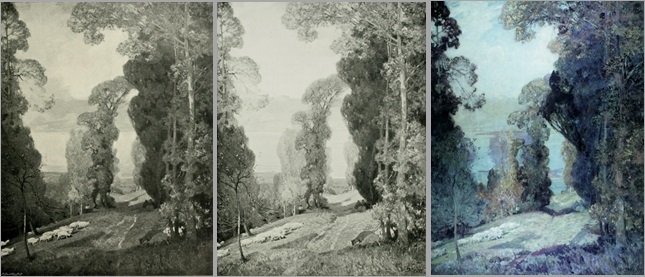

These preparatory designs or ‘underdrawings’ are often obscured entirely by subsequent applications of paint and are therefore invisible to the naked eye. However, the carbon content of traditional underdrawing media ensures that they can be seen using infrared reflectography; an imaging technique that makes use of the longer wavelengths of infrared radiation to penetrate the upper paint layers and reveal the drawing below (Fig.). This method was used to uncover the detailed underdrawing used for the Fitzwilliam painting. Through scrutinising the intricate draughtsmanship that provided the basis for the composition Joos van Cleve’s mastery is fully revealed. A variety of lines were used to create an initial sketch for the composition, ranging from the curved outlines of the infant Christ’s flesh to the more angular and hatched marks used to indicate the folds of the Virgin’s robe. In contrast to the detailed design reserved for the figures and drapery, there appears to be no underdrawing present for the landscape. It is possible Joos van Cleve had an apprentice in his workshop who filled in this part of the composition without the use of a preparatory design, as it was common to have students and trainees specialise in painting various parts of the painting.

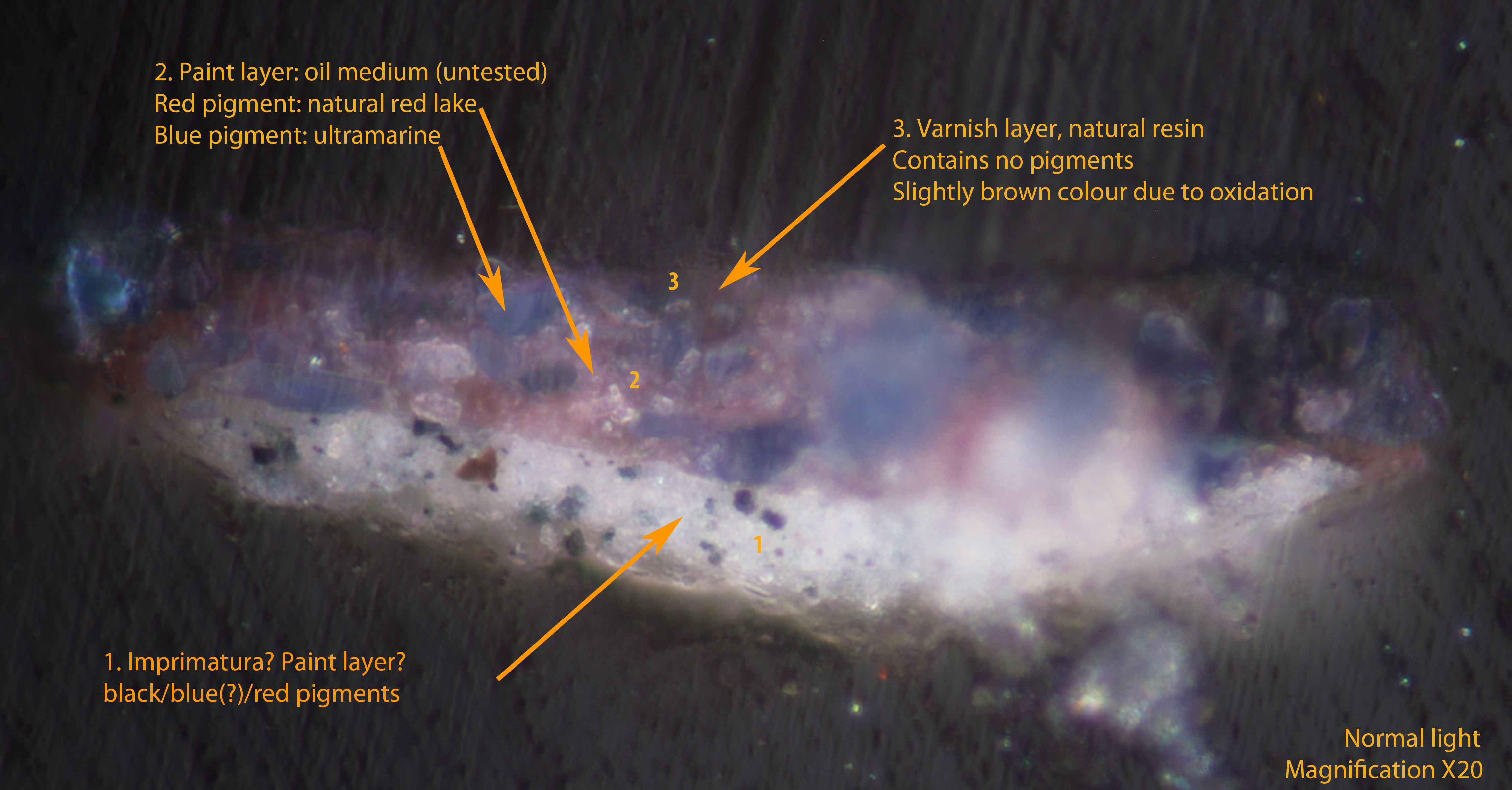

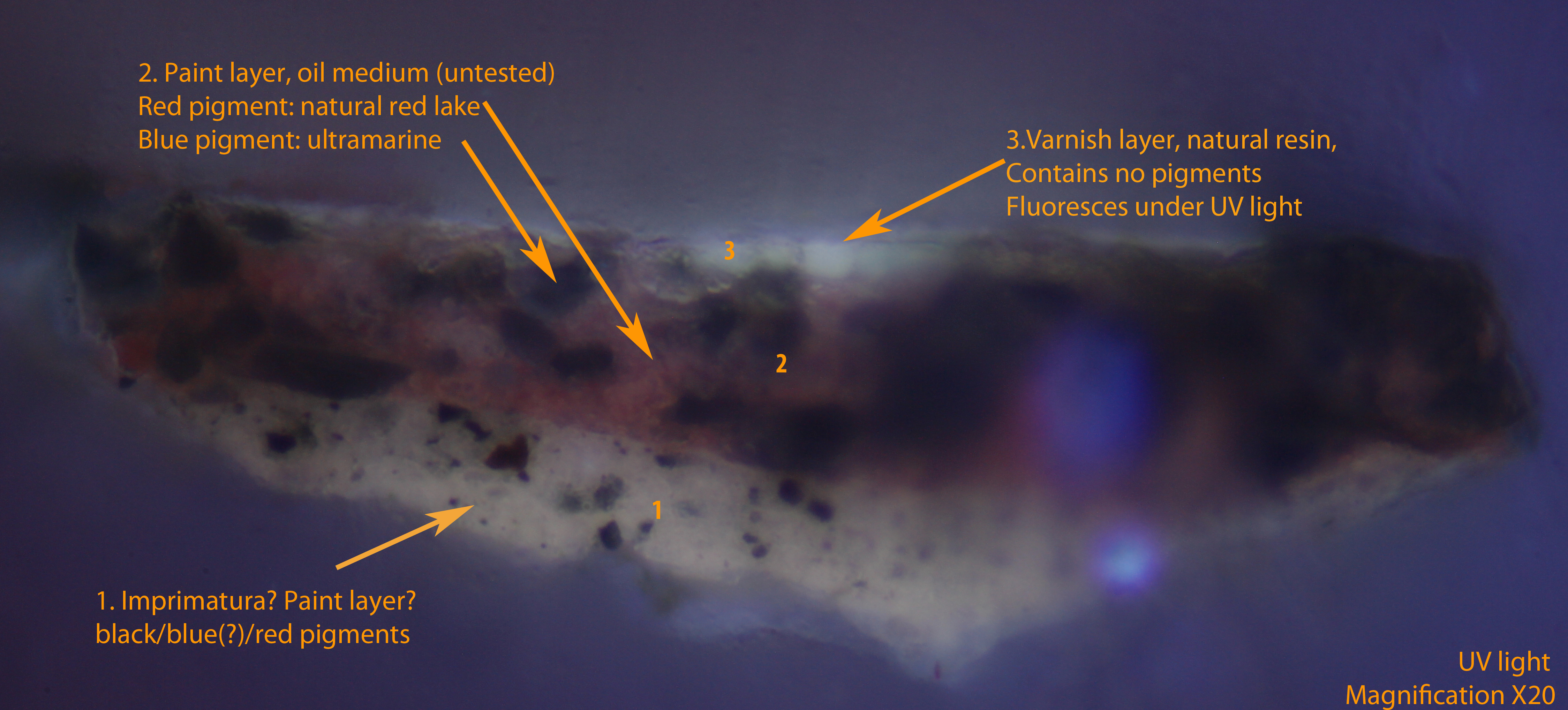

Once the underdrawing was complete the paint was applied using very thin layers. The darker passages of the painting consist of several transparent layers painted on top of each other to give depth, exemplified by the folds of the Virgin’s robe and the darker tones of the landscape. Finally, the painting would have been finished through the application of a varnish, which most likely consisted of a natural resin dissolved in spirit or cooked in oil. The purpose of a varnish is to saturate the colours within the painting, creating a sense of depth, whilst also harmonising the various tones throughout the composition.

Conservation treatment

The initial treatment step consisted of surface cleaning to remove the thin layer of dust and grime that had accumulated on the painting’s surface over time. The varnish was then removed using organic solvents, which were chosen based on previous cleaning tests. The yellowed appearance of the varnish had a flattening effect on the shapes within the composition, whilst also dulling the vibrancy of the colours. The removal of the varnish revealed a significant visual improvement for the painting. However, this was only the beginning. Underneath the varnish a grey layer of dirt continued to obscure the colours within the composition and its removal brought even more luminosity to the surface of the painting. In addition, a campaign of overpaint covered passages of old abrasions and losses, most notably in the red cloak of the Virgin and the tree on the right-hand side of the painting (these passages of overpaint are marked using red in the lower right photograph).

After the removal of the final dirt layer a very old, degraded layer of varnish remained on the cloth of honour behind the Virgin. It is possible that this localised coating was left by a previous restorer, perhaps due to the sensitivity of the paint in this area to organic solvents. The cloth, originally blue, had acquired a brownish-grey tint. Microscopic samples were taken from the painting to establish whether this layer was original or not. Examination of the samples in cross section indicated that the grey layer consisted of an old, oxidised varnish, as opposed to a pigment-containing glaze. The cross section samples further showed that the layer underneath contained blue and red pigment particles, creating an optical purple colour (see below). However, after cleaning the colour revealed showed a slightly more blue hue, most likely due to the photo-degradation and resultant fading of the organic red lake used for the optical mixture.

Polkownik)

Polkownik)

Polkownik)

Polkownik)Once it was clear that the uppermost degraded varnish layer was not pigmented, and therefore not considered original, we proceeded with the removal of this layer. The picture below shows the right side of the cloth after cleaning, revealing a vibrant purplish blue, while the left side is still covered by the discoloured varnish.

Polkownik)

Polkownik)After the cleaning was complete, the painting was re-varnished using a modern synthetic resin that will not yellow upon ageing. The losses were filled using a water-soluble putty consisting of gelatin and chalk, and the fills were retouched using synthetic resin and pigments. All of the phases of the restoration, including varnish, fills and retouching are designed to be completely reversible, to facilitate their easy removal in the future.

(Click to enlarge photos)

Although this painting came to the Hamilton Kerr Institute for minor restoration in preparation for an exhibition, the treatment served the purpose of uncovering the hidden brightness of the colours, whilst also bringing forth the previously flattened volumes and shapes within the composition, most notably in the delicate sfumato of the Virgin’s face. The opportunity to restore such a beautiful and exceptionally well preserved painting was extremely enjoyable, whilst observing the mastery of Joos van Cleve in such detail helped broaden my understanding of 15th century Flemish painting technique.

Camille Polkownik – 2nd year Post Graduate Intern (2015-2017)

The Madonnas and Miracles exhibition (video)

About the Author

Ms Camille Polkownik graduated with a Master’s Degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Paintings in 2014, from the École nationale supérieure des arts visuels de La Cambre in Brussels (Belgium). She also has a Bachelor degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Painted Works (2011) from the Superior School of Fine Arts, in Avignon (France). She has interned in the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Belgium), the Royal Museums of Fine Art of Brussels (Belgium), the Museum of Fine Arts in Nice (France), at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia) and in private studios.

Her current research projects include the study of extenders added to Prussian Blue from 18th to 20th century in Europe, while matching and comparing paint samples to historic sources, and the characterisation of an unusual form of lead white called “Prismatic Lead White”.

To contact Camille Polkownik: camille.polkownik@gmail.com