This blog post is about the reconstruction of a painting by the Italian artist Pinturicchio, which depicts the Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. The painting dates to c. 1495 and is currently in the Fitzwilliam Museum Collection in Cambridge.

Bernardino di Betto di Biagio, who went by the name Pinturicchio, is considered one of the more traditional Italian painters of the early Renaissance and is best known for his frescoes rather than his easel paintings. This is in part because of a crushing condemnation of his work by Giorgio Vasari in the 16th century: “Often Fortune ignores the worthy and helps the unworthy, because it flatters her that by her favours there should be exalted those who would never reach distinction on their own.”(Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 25, No. 1/2 (Jan. – Jun., 1962), pp. 35-55)

I chose this painting because it came from a different period of early Italian art to the painting that was reconstructed by my co-student, Anna Don. I felt it would be good to be able to compare the two different styles of painting through first-hand experience of their preparation and technique. The lush green landscape and miniature figures in the background also appealed to me.

For first-year reconstructions at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, we have the fantastic opportunity of having the paintings we are replicating in the studio with us. This is a huge advantage when trying to reconstruct artists’ processes, as we can constantly refer to the original. Kari Rayner, 1st year intern, treated the painting in preparation for the “Madonnas and Miracles” exhibition.

Having now spent the better part of a few months with Pinturicchio’s Madonna and Child, trying to recreate how it would have originally been painted, I have been led to disagree with Vasari’s assessment of Pinturicchio’s work, and I wholly encourage you to go and admire the painting at the Fitzwilliam Museum where it is part of the new “Madonnas and Miracles” exhibition.

Support

Unlike most panels made in Italy from this period, Pinturicchio’s painting was not executed on a poplar panel. Poplar was used more out of lack of options than a preference for the wood itself and artists would use other available woods such as walnut if they could. Adopting this view of accessible materials, the reconstructions were made on pine wood, which warped during the making of the reconstructions.

I primed two panels, one with canvas beneath the gesso ground and one without. Canvas on panels became less popular during the 15th century. However, the theory behind its use was to help cover knots and cracks in the wood and to provide a uniform surface for the gesso. The second panel was used as a test panel, which was invaluable throughout the reconstruction process.

Ground

The ground itself is made up of two parts. The first layer is Gesso Grosso, a form of calcium sulphate (for our reconstructions I used hemihydrate, better known as Plaster of Paris), mulled with warm rabbit skin glue which provides the bulk of the ground.

The gesso grosso was applied with a spatula. Taking some advice from a plasterer, I found it easiest to use a large spatula and apply the layers quickly. For my panel primed with canvas, I had problems with air bubbles in the gesso disrupting the surface. They were such an issue that after several applications I decided to wash the gesso off entirely and apply with a cloth and start again. The second time I applied the first few layers with my fingers to ensure that the canvas was fully saturated with gesso and this worked quite well.

The second part of the ground is Gesso Sottile, slaked calcium sulphate mulled with warm rabbit skin glue, that forms a silky smooth surface for the paint layer. To be more historically accurate, the sottile would have been scraped down until smooth and then rubbed smoother with the plant Mare’s Tail. However, as achieving this level of historical accuracy would also have required, according to Cennino Cennini’s Il Libro dell’Arte, several years of apprenticeship to perfect, I opted for fine sandpaper.

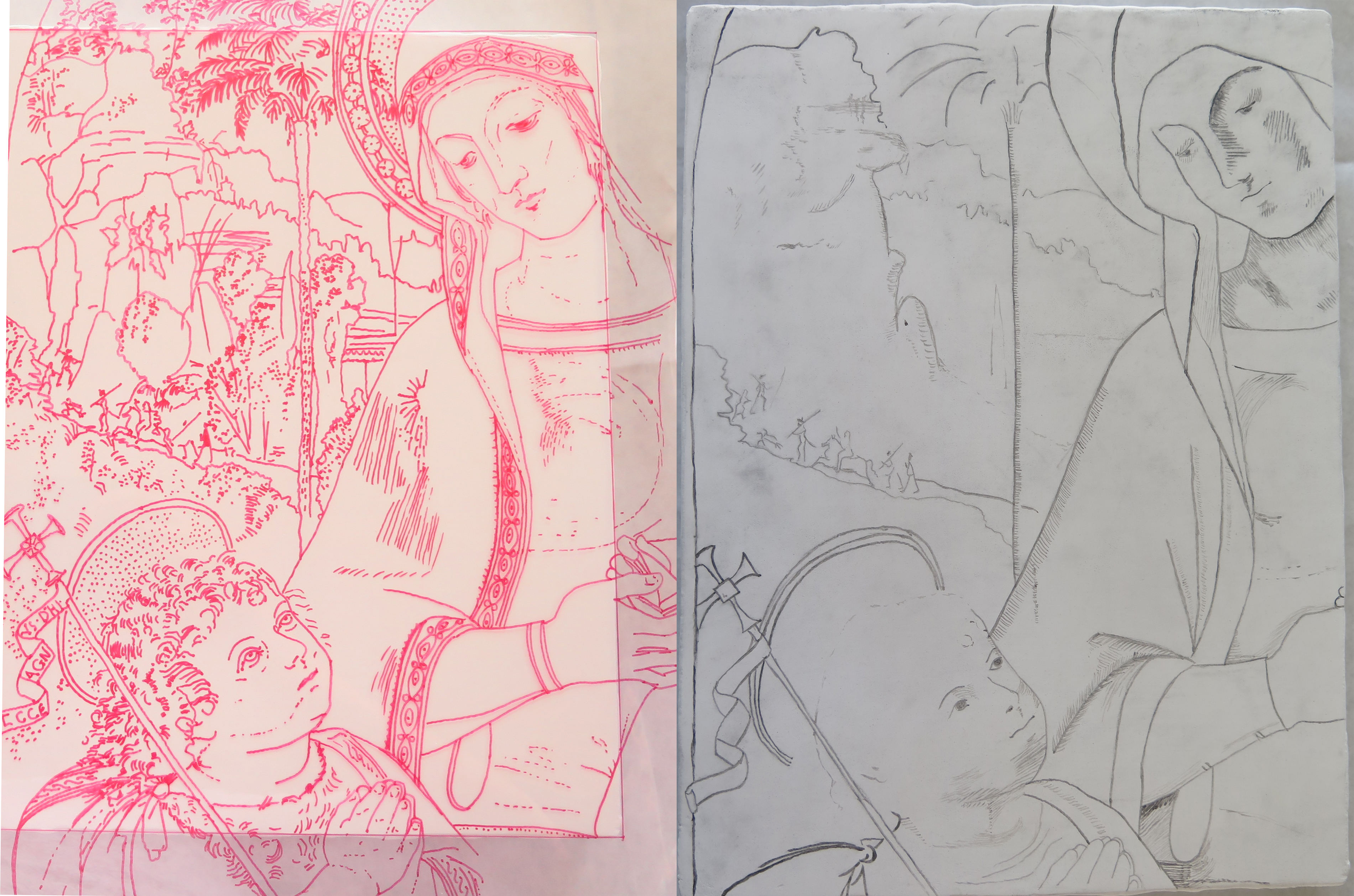

Underdrawing

The underdrawing was done by tracing the original painting onto a sheet of melinex (a process that is harmless for the painting but disconcerting for the tracer). Next, a sheet of paper covered in charcoal was placed charcoal down on the primed panel and the melinex tracing placed on top. The image could then be transferred by re-tracing the tracing with a sharpened point. I finally went over the charcoal transfer with ink and brushed away the excess charcoal. This part of the reconstruction process was easy enough to do, but I was surprised by how much my tracing of the painting could still be identified as mine. I had managed to lose something of the character of the original and replace it with something of my own. It was a very visual reminder for me that this process, though historically informed, was not entirely objective.

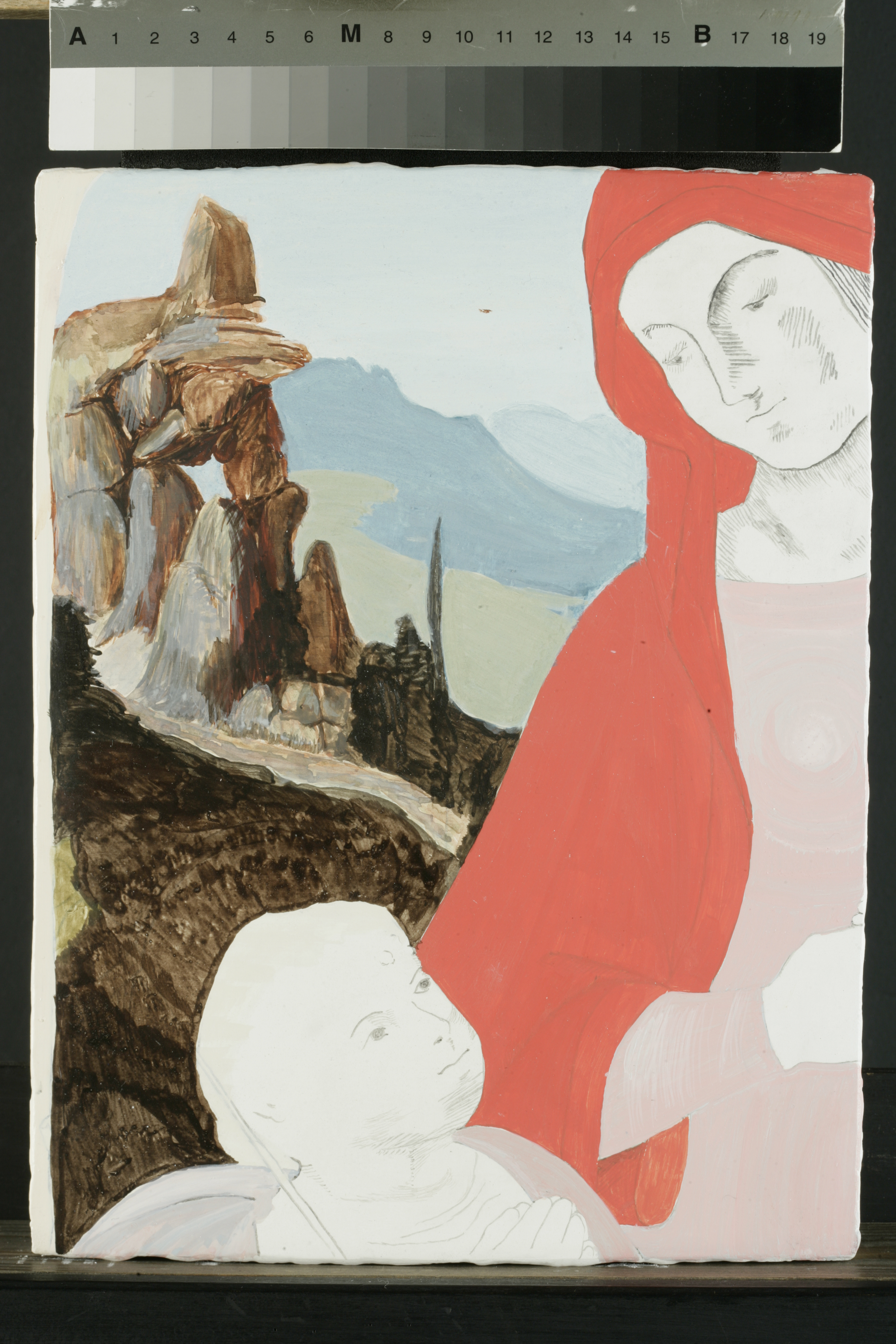

Painting

Egg tempera, consisting of egg yolk and water, is a painting method that is often associated exclusively with early Italian work. It is incredibly quick drying, thus the diverse palette that Pinturicchio appears to have used for his Virgin and Child meant that a frustrating amount of time was spent grinding pigments into new paints.

The pigment that presented the most challenges to mix was lead white. Initially , it was suggested that lead white be avoided because of the associated health risks. However, I found that the titanium white I had substituted dulled down the colours and did not provide adequate coverage, which made me try out lead white under controlled conditions. I found that the flake white I was using was not mixing well with my egg yolk medium. This was resolved by adding a few drops of alcohol which acted as a wetting agent before mulling it with the egg yolk. Alcohol is not a part of any historic recipe I could find, but it is possible that the modern pigment particles that I was using were too small, causing bad dispersion behaviour. The lead white certainly acted like cocoa powder that stubbornly refuses to wet into the milk no matter how much you mash it with a spoon. The preparation of lead white was well worth the trouble as it was one of the nicest pigments to handle.

For the painting proper, I followed the advice of Cennini and began with a vermilion, white and ochre underpainting for the Virgin’s blue robe. This underpainting was visible as a discoloured red through some previous losses in the blue azurite of the robe. The purpose of this layer was to create a warm underlayer for the coarse azurite and prevent it from appearing greenish.

I then started on the background, the next step suggested by Cennini, and the area that had first attracted me to the painting. On other early Italian paintings, there appears to be a very formulaic approach to applying colours, but no matter how much I looked at the landscape in Pinturicchio’s painting, I could not work out any order to his colour application. I concluded in the end that Pinturicchio was possibly a bit more experimental and might have reworked passages, overlaying different hues.

The faces followed the traditional approach to tempera painting, starting with a green earth layer and verdaccio that sits underneath the flesh tones of the faces and now, several hundred years later, is clearly visible through the upper layers of paint. This was followed by a build up of fine-hatched tempera. At first I found it very easy to overwork passages and on the face of the Virgin there are sections that have too many layers as I kept returning to tweak colours.

Glazes

Like many of the later Italian tempera painters, Pinturicchio also made use of oil glazes in his paintings. Red lake and copper resinate glazes were often used on red and green fabrics and draperies to create an illusion of richness and depth. It appears Pinturicchio used a copper resinate glaze in the background to create the lush, three-dimensional landscape, and red lake on the draperies to increase the illusion of depth. Despite having several shades of hand-made red lake, I found it was the most difficult pigment to match. It was too pale, leading me to believe I had done far too little modeling in the underlayers. I even tried to apply the madder in thicker layers to see if I could achieve a darker effect. However, this caused wrinkling of the glaze upon drying. I did eventually find a madder that was a much deeper colour and I managed to achieve something closer to the original intensity. The result was much better but proved that I could still have done more under modeling of the draperies.

Glazing the areas of foliage with copper resinate (verdigris dissolved in a oil and resin medium) was an exercise in working out how much modeling was needed in the tempera underlayers. My conclusion was that maximum modeling should be done in the tempera layers and minimal modeling in the glazes, which I applied in thin layers to try and achieve the textured, almost impasto effect of Pinturicchio’s surface.

Mordant Gilding

The mordant gilding presented a completely new set of challenges for this reconstruction. This was because the gilding had adhered over very coarse pigment, (high grade azurite) and/or over oil glazes. I noticed that in a small trial area, these painted layers had acted as a mordant in their own right and prevented the brushing off of excess gold leaf.

Several treatises recommend glare (an egg white-based temporary varnish) as an isolating layer between oil and mordant. I tried a recipe which included some sugar in the hope that it would be easier to remove, and was fairly successful but there were still issues with removing excess gold. Many treatises recommend that certain processes should be carried out at certain times of year to allow for favourable weather conditions. For example, the gesso application should not be done when it is too hot to prevent cracking. I suspect mordant gilding over the glaze during drier atmospheric conditions might make a difference.

The other issue I faced was entirely my fault and could have been prevented. When applying the mordant for John the Baptist’s halo, I realised that it was indistinguishable in colour from the green background, which resulted in a halo that was not as perfectly rounded as the original and gave John the Baptist’s halo the illusion of trying to turn itself into a wizard’s hat.

The final touch was shell gold added as a multitude of highlights to the landscape to create what Cennini refers to as, “a Garden of Eden”. It was unclear from the original how much of the gold was original and how much was from subsequent campaigns of restoration as some appeared very shiny. I therefore decided to add shell gold until a point I felt the image looked complete. This was influenced by working under the knowledge that the early Italians were rather fond of their bling.

It seems that in some ways, this reconstruction has been an exercise in exploring how Pintoricchio probably did not paint his Madonna and Child. This was one of the most useful outcomes of the reconstruction process, where discovering that a preconceived idea has not worked in practical terms, which allowed us to go back to the painting with fresh eyes.

The main result of this reconstruction for me was two-fold. Using (most of the time) historically accurate materials gave a practical framework to apply the theory we learn as part of the course. The other was less tangible but more profound. I gained a deep respect for Pinturicchio and other artists of the age. Throughout the process, the way I looked at the painting changed, and understanding a bit more about the framework within which early Italian artists worked only made me appreciate the achievements of their success more.

Now that you have seen the behind-the-layers of this artwork, aren’t you curious to see what it looks like on the wall? Come admire the painting at the (free) exhibition “Madonnas and Miracles” at the Fitzwilliam Museum!

Elisabeth Petrina, 1st year student at the Hamilton Kerr Institute

Elisabeth Petrina is the second of the new students. She received a fine art foundation diploma from Exeter College and BSc (Hons) in Chemistry from the University of Liverpool before disappearing to Croatia for several years to set up a forensic ornithology unit and grow vegetables. She has undertaken a project to establish a pigment garden at the Hamilton Kerr Institute that can be used as a research aid in future years.

To contact Elisabeth: ep497@cam.ac.uk