William Thackeray’s hand in The Human Touch exhibition contains tantalising clues to the trade secrets of master Victorian plaster-cast maker Domenico Brucciani.

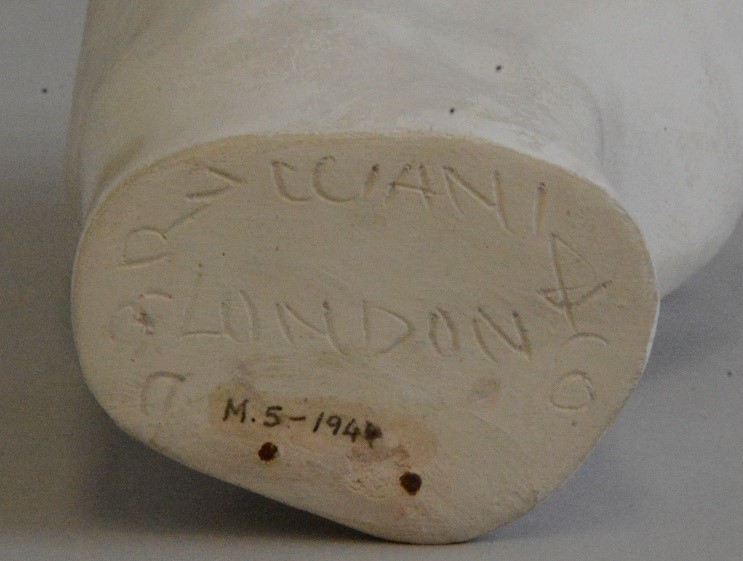

I will admit it up front: I have been making casts of hands and faces from myself and family members on and off since I was a young teenager; so I was particularly intrigued by the cast of William Makepeace Thackeray’s hand (Museum number M.5-1944) which I recently conserved for the exhibition ‘The Human Touch: making art, leaving traces’ (open from 18th May to 1st August 2021).

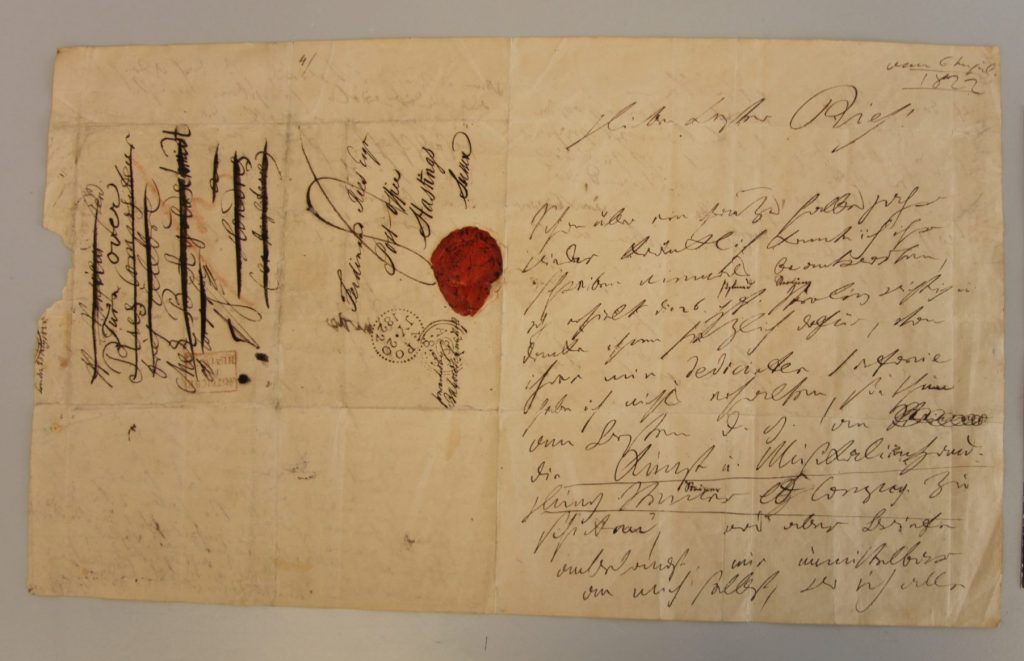

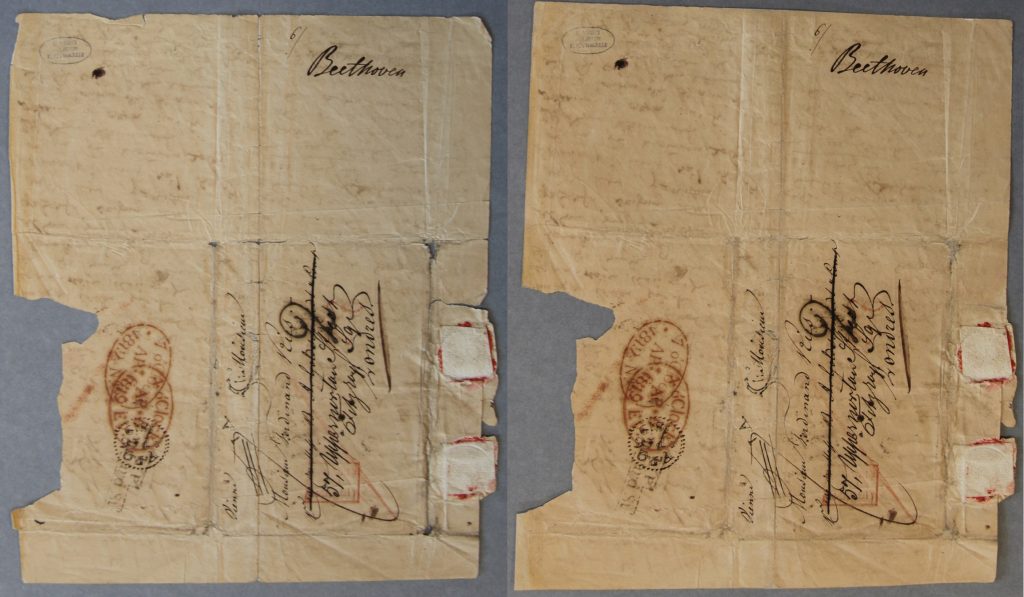

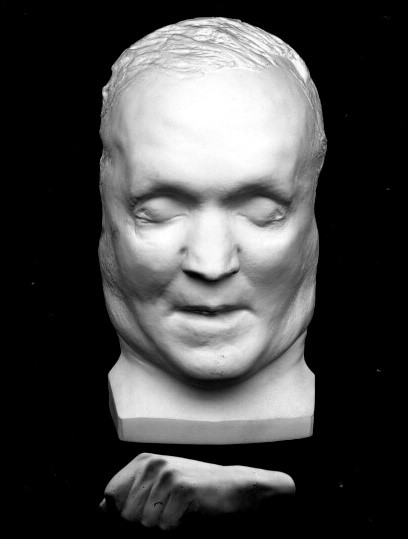

The mould for Thackeray’s hand was made on Christmas Day 1863. Thackeray had died suddenly the day before, aged just 52. His doctor and friend Sir Henry Thompson was called to confirm the death, and it was he who also sent for the famous and highly respected cast-maker, Domenico Brucciani, to make casts of Thackeray’s face and right hand. The National Portrait Gallery has copies of both.

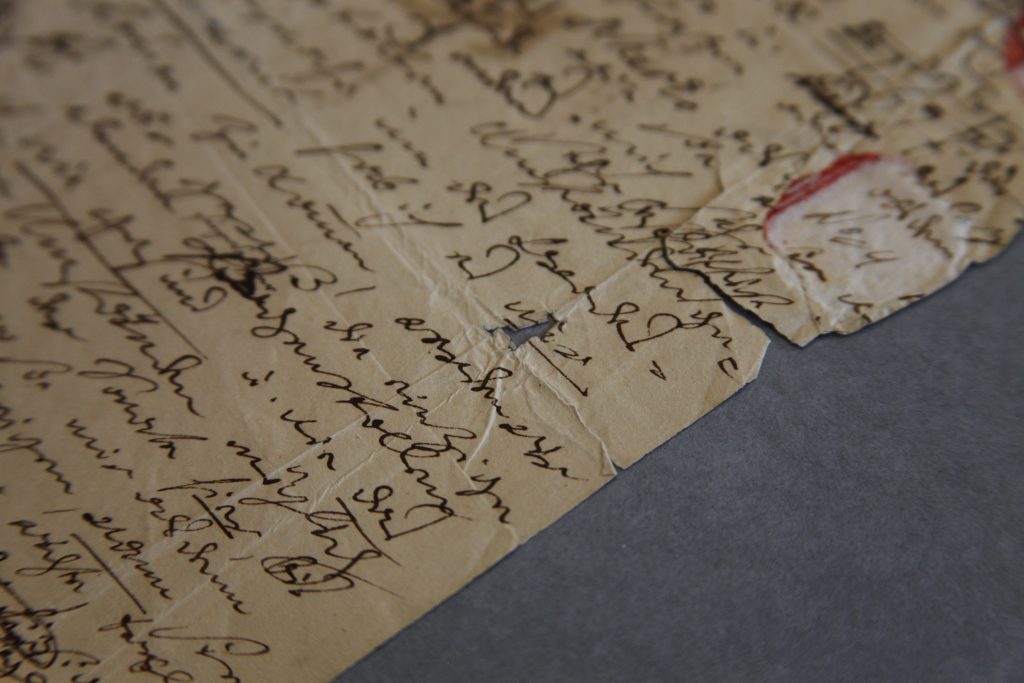

The only other known copy of the hand is the one in the Fitzwilliam Museum, which was given to us in 1944 by Henry Thompson’s son, Herbert. It came with a note written by Henry, which says ‘It is characteristic, recalling for me the original with its long and delicate fingers, the form of the nails &c, very forcibly’.

The cast hand has its own special red leather case, similar to a jewellery case but somewhat resembling a very small coffin.

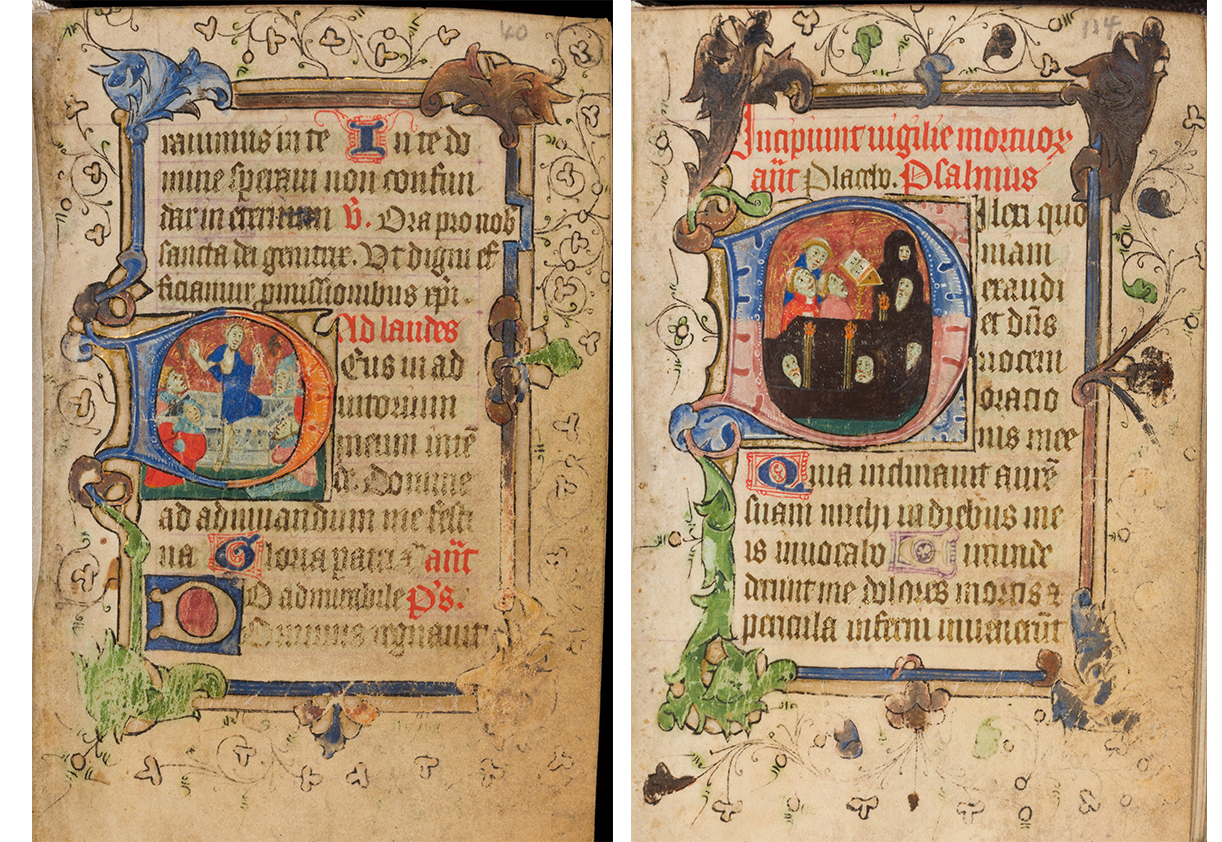

So why did Thompson commission casts of Thackeray’s head and hand? Although death-masks have been made for many centuries in different cultures, they were particularly popular in Victorian times. Before photography was widely available, they served as an affordable memento of a loved one who had died. They were also made fashionable by the pseudo-science of phrenology, which suggested that a person’s character was evident from the shape of their skull. This stimulated demand for copies of the cast heads of famous individuals, whether they were the great and good or heinous criminals. Thackeray was ranked second only to Dickens in his own time, and there would surely have been public interest in his death-mask. But his family very much opposed making the mask and hand widely available and insisted that Brucciani should not make any further copies of them, so in this case they were made purely as personal mementoes.

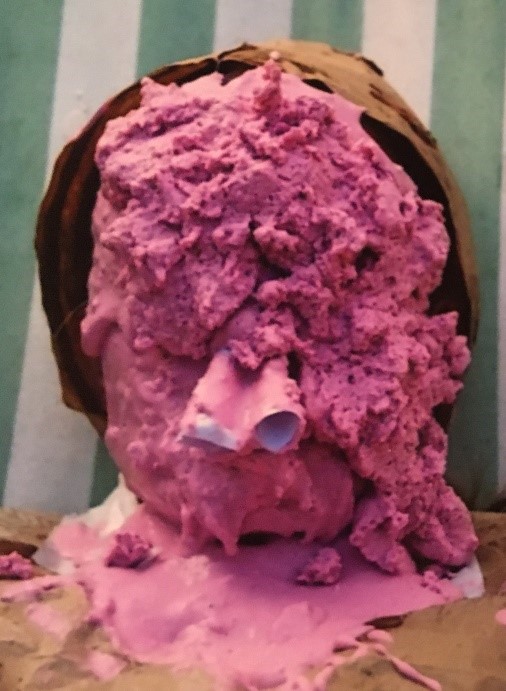

Taking a cast from a person’s head is quite an undertaking. A few years ago, my daughter very sportingly allowed her parents to cast her face. After generously applying Vaseline so that her eyelashes, eyebrows and downy hair would not be pulled out in the process, we made a mould using alginate powder, which is a rubbery casting compound:

The pink blobs are the alginate mixture and the two cones are paper tubes which my daughter inserted up her nostrils so she could breathe during the few minutes it took for the alginate to harden enough to be removed. This is the aspect of the process which sometimes makes people panic and pull off the mould before it solidifies: it can be pretty stressful to have to stay absolutely still and breathe only through straws up your nose while someone piles the moulding material onto your face!

Casting the head of a real person is clearly quite invasive, whether the subject is dead or alive, and not everyone was willing to submit their very recently deceased loved one to the process. Luigi Finili, who was at one time Brucciani’s chief moulder, said in an interview with the Pall Mall Gazette in 1892: ‘Many people prefer to have a model of their dead friend’s hand instead of the face. They do not care to let anyone touch the face, but they do not seem to mind so much about the hand.’ Even when a death mask was made, it was often disappointing. Jack C. Rich in his classic work, The Materials and Methods of Sculpture (1947) explained that ‘There is a tendency of the facial tissues to sag with gravitational pull when the subject is in a horizontal position. This phenomenon is particularly marked with older and more obese persons.’

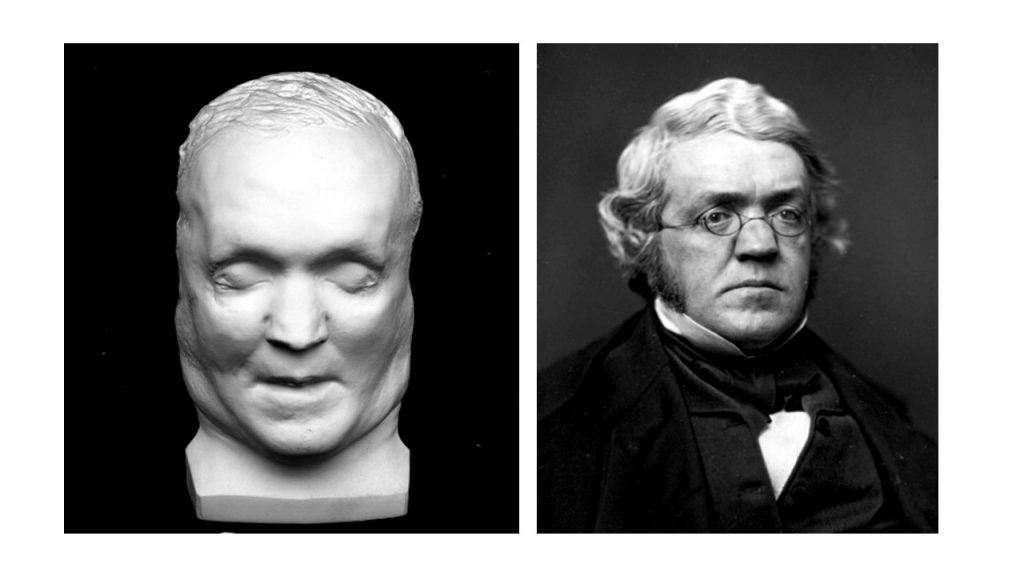

Even when a cast is made from an upright model this can still be a problem – the mask we made from my young daughter was also quite distorted by the pressure of the moulding material on her face. A cast from life may also fail to resemble the subject because it lacks colour and expression, while features like hair and spectacles which contribute strongly to many people’s appearance are hard to reproduce in a plaster cast. Comparing the death- mask of Thackeray with even a very static-looking photograph of him from 1855 gives an idea of the problem.

‘By some mischance the [face] was not agreeable, [with] none of the charm of expression so attractive in life & it was rejected. But the hand is a portrait and recalls to me very strongly the character of the original.’

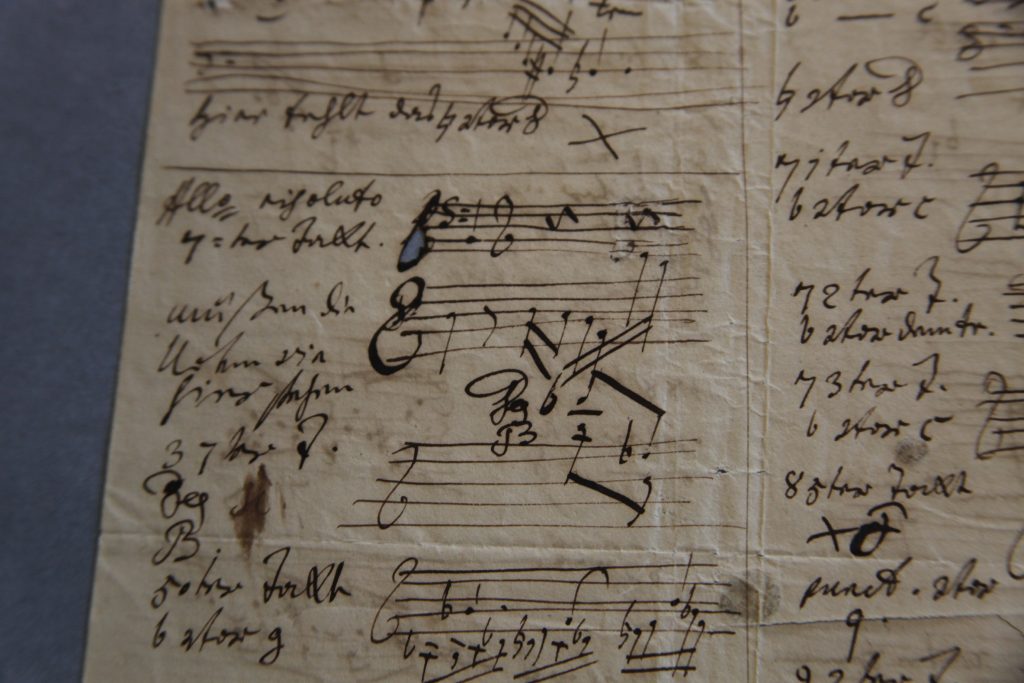

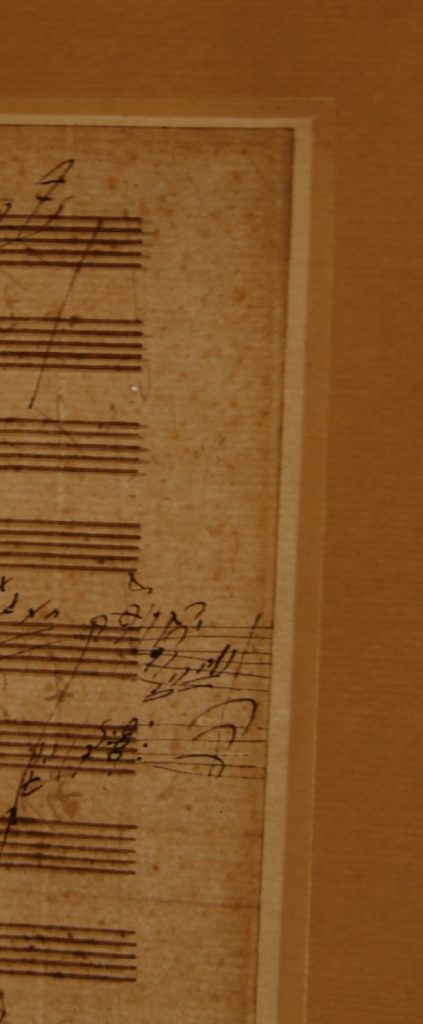

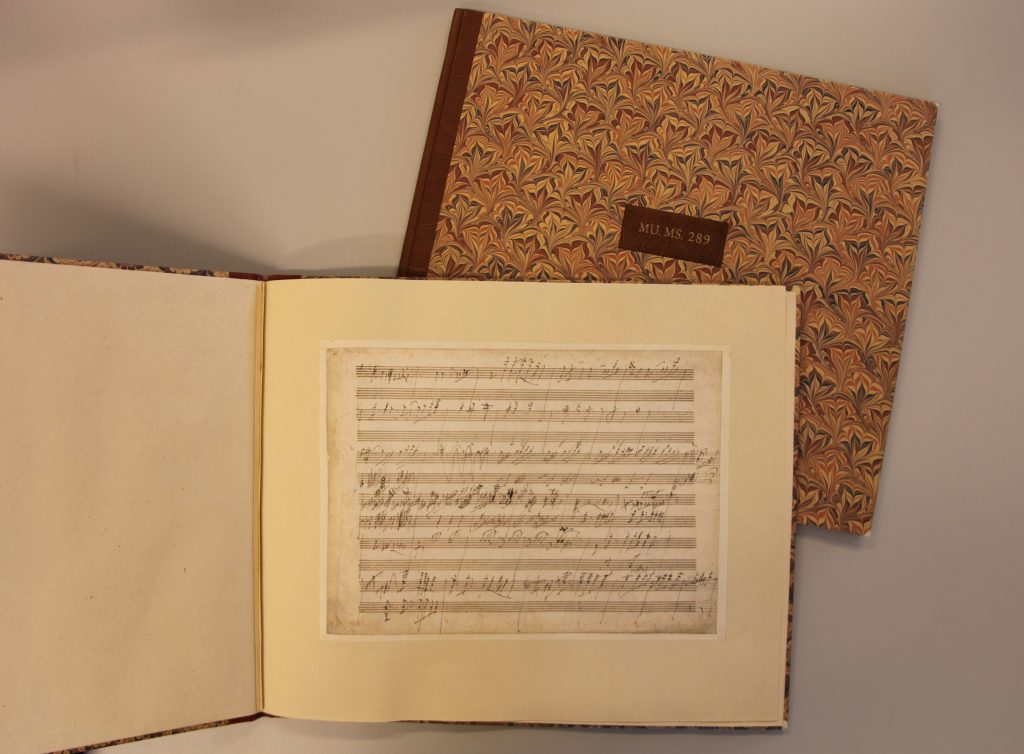

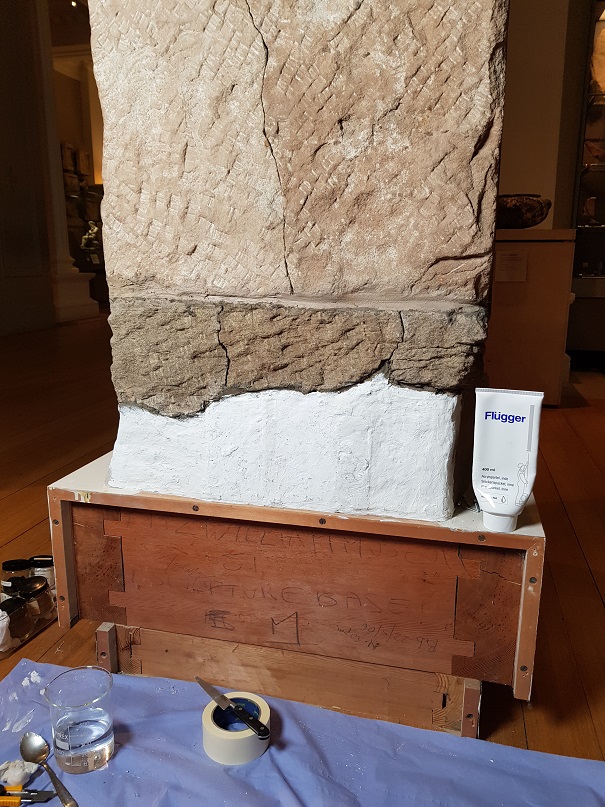

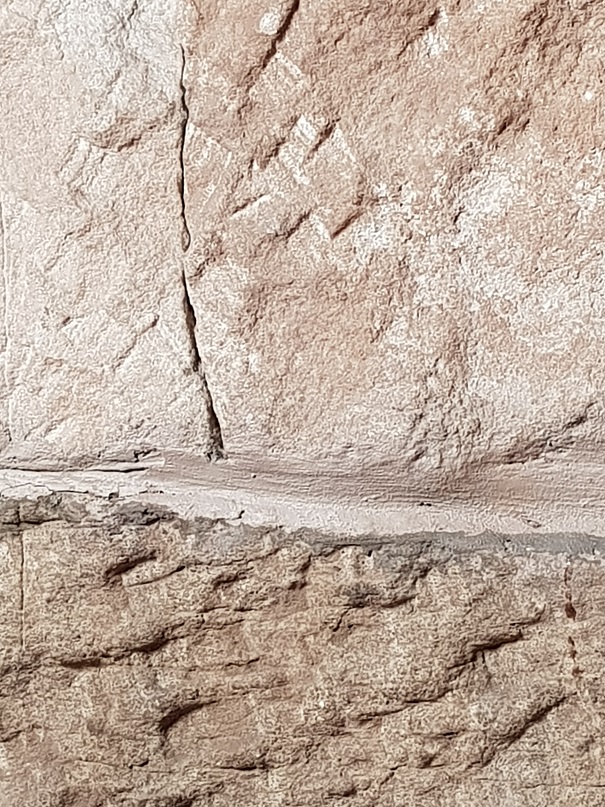

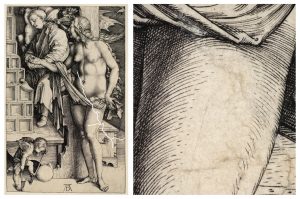

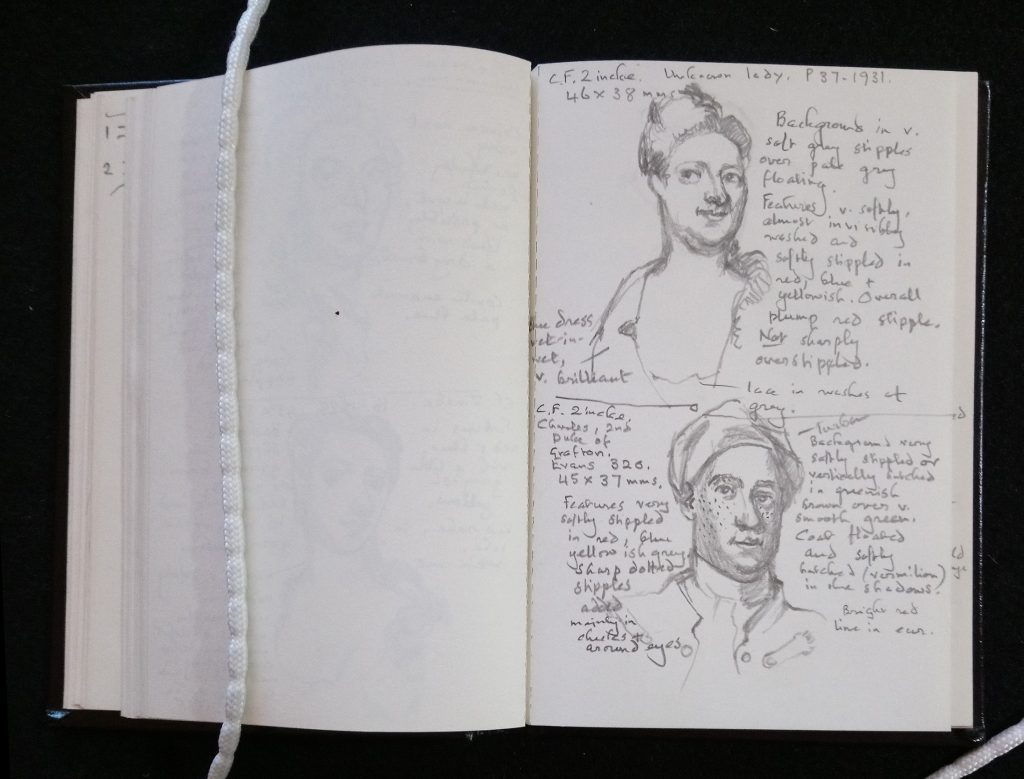

When looking in detail at the cast of the hand, it is clear that it was made by a very skilled craftsman. The plaster is fine and there are no air bubbles visible at all. This can be very hard for an amateur like me to achieve. The detail on the surface is very clear, with the grain of the skin visible in places when the hand is viewed under the microscope. Small losses from the surface reveal more about the technique Brucciani used to achieve this fine detail. He seems to have poured a very fine plaster mix into the mould first to get a thin ‘skin’ layer, allowing this to set partially and then filling the rest of the mould with a coarser plaster mix.

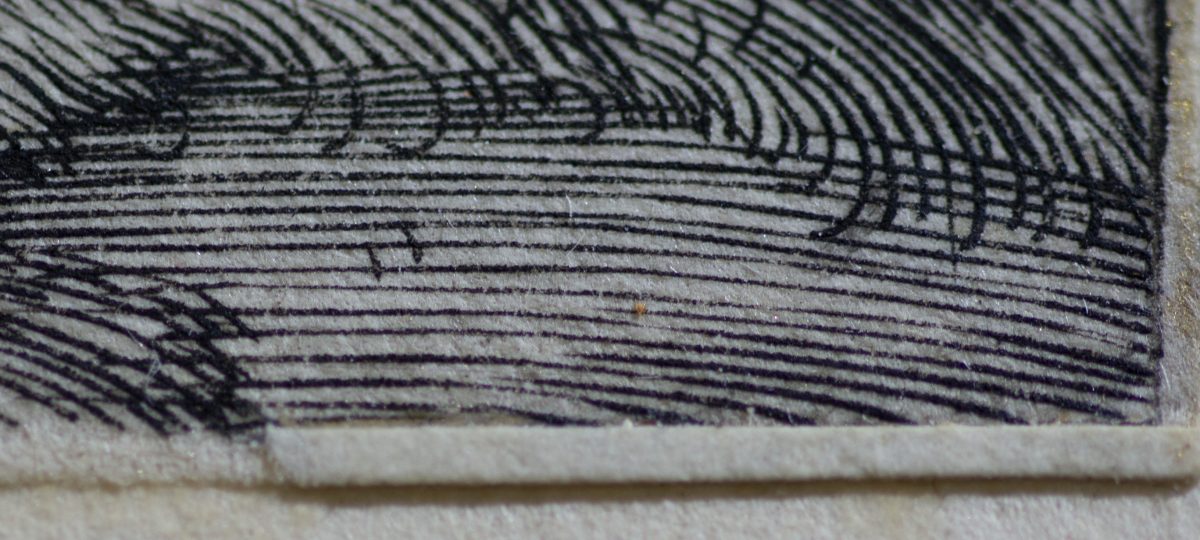

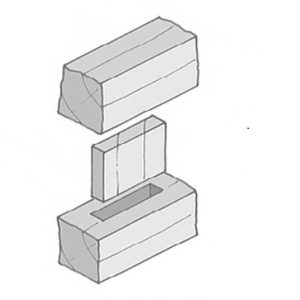

Brucciani’s skill at finishing the cast also makes it hard to tell if the mould was made in sections or cast in a soft mould. A clenched human hand has a number of ‘undercuts’ which would make it impossible to remove from a hard plaster mould made in a single piece – it would need to be made in sections. The traditional method of doing this involves using a fine wire or waxed thread to split the mould around the hand. This technique is tricky to master because it relies on expert timing. Threads are laid on the surface of the hand in the places where splits in the mould are needed. They are then pulled out at exactly the right moment while the plaster is setting, to split the mould so it can be removed in sections. If the thread is pulled too soon the soft plaster flows around the place where it was and re-joins the sections of the mould; if it is left too late, the thread may break when it is pulled or even be unable to split the hardened plaster.

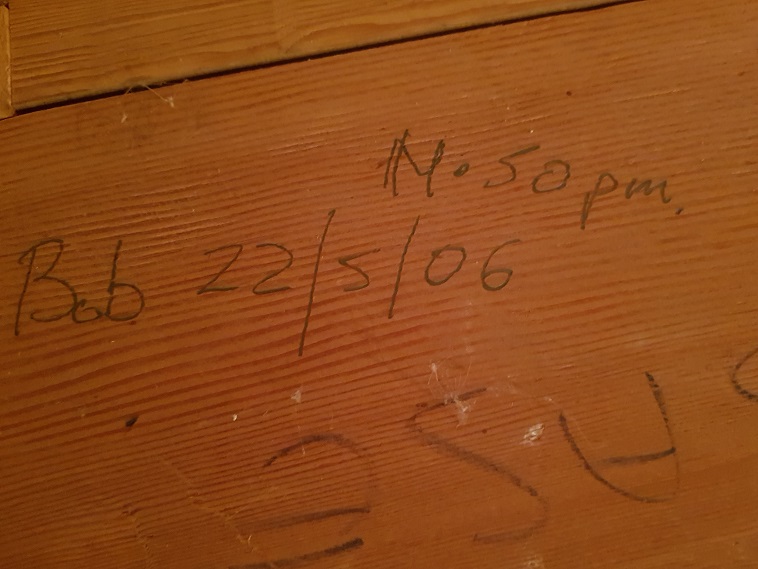

The alternative to this hard plaster mould method is to use a soft moulding technique, similar to the alginate we used for my daughter’s face mould. Alginate was not available in 1863, but soft moulds made from gelatine had recently been invented. It is sometimes said that this technique was invented around 1865, when it was used by another well-known cast-maker, Giovanni Franchi, to cast Pisano’s 14th-century marble pulpit in Pisa Cathedral for the famous V&A cast collection. But Brucciani was already using the technique in 1861, when he got into trouble with the British Museum for allegedly staining a Classical mausoleum while casting it using gelatine. He was actually banned from using the process at the British Museum again without express permission from the Museum’s Trustees – but of course he was still free to use it in projects for other clients.

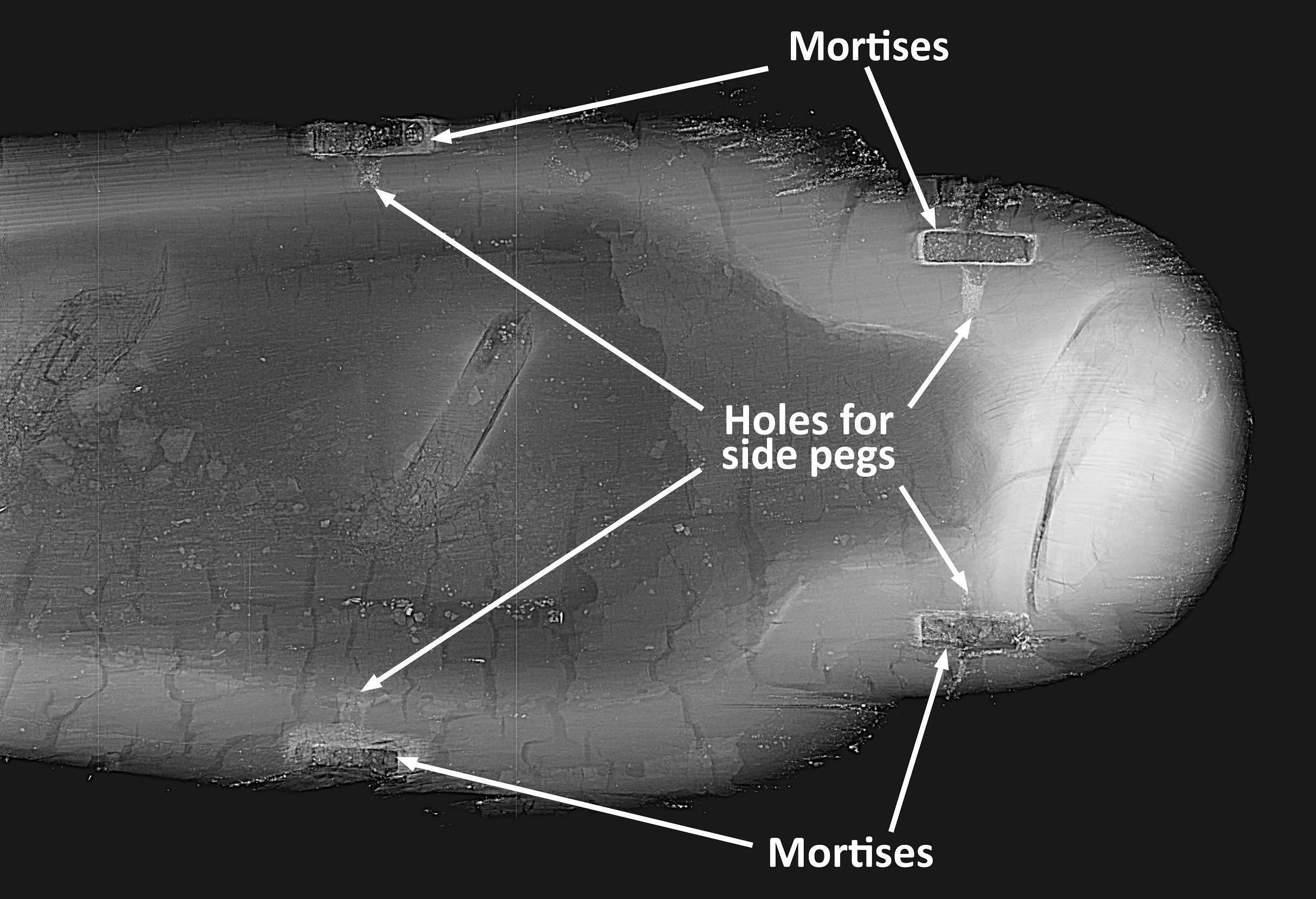

Gelatine moulds were suitable for making both small and large casts and had the advantage that the final result would not have the seam lines that you get when casting from hard moulds made in sections. Brucciani’s skill was such that it is not easy to tell whether there were seams on Thackeray’s hand that have been removed; but the stumps of two iron pins in the wrist may provide a clue.

Plaster heats up quite a lot as it sets. When using a gelatine mould it is important to remove the cast as soon as the plaster is firm enough so that this heat doesn’t melt the gelatine, or the mould cannot be reused. The iron pins may be the remains of a hook used to help pull the cast out of the soft mould quickly. Once the cast was removed, the hook could be snipped off as it would no longer be needed.

Spending time with the cast of Thackeray’s hand has made me wonder about the maker, Domenico Brucciani. He came to England from Italy around 1829, when he was just 15, and joined his uncle’s plaster-cast business in Covent Garden. He stayed in England until his death in 1880. Unlike most Italian itinerant ‘image-sellers’ at the time, he built a very successful business known for quality, riding a wave of democratization of art, both for people’s homes but also for the great museums and art schools of his day. He headed a large firm which was responsible for many casts in the V&A, British Museum and Royal Academy, and exhibited his work at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the International Exhibition of 1862.

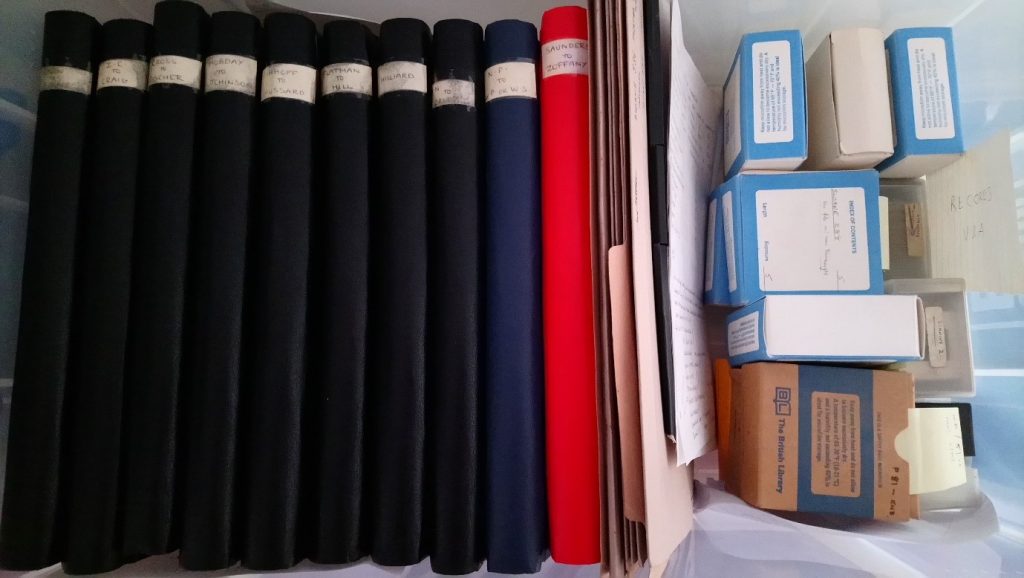

A fascinating recent book by Rebecca Wade, Domenico Brucciani and the formatori of 19th Century Britain (2018) discusses his career and the plaster-casting industry in depth, and yet, despite his renown, Brucciani remains a rather shadowy figure. A short obituary published in The Builder in April 1880 said ‘although chiefly a plasterman in calling, he was an artist at heart’. The beautifully made death-hand of Thackeray bears witness not only to the famous writer, but also to the craftsman who made it.

‘The Human Touch: making art, leaving traces’ is open from 18th May to 1st August 2021, and tickets are available to book online.