Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist (Fig. 1a-1b) was brought to the Hamilton Kerr Institute for treatment in the spring of 2016 prior to the painting’s display in the Madonnas and Miracles exhibition. While the painting’s condition was stable when it arrived, the varnish was dull and slightly greyish, and it was decided that varnish removal would provide an aesthetic improvement. Although the treatment was not particularly complex, I found studying the materials and techniques Pinturicchio used in this work and researching the painting’s treatment history to be a rewarding and edifying experience.

Virgin and Child dates to 1490-1495 and was acquired by the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1880. This work is only one of numerous paintings by Pinturicchio of this subject, with two of the most closely related versions in the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Variations in the paint handling and quality of these works may be attributed to the involvement of workshop assistants.

Materials and Technique

Pinturicchio painted the Fitzwilliam’s Virgin and Child primarily in egg tempera, enriched with oil glazes and gilding. As was traditional in Italian paintings of this period, the flesh tones are underpainted with a greenish layer termed verdaccio. Additionally, dispersed pigment samples were taken from the Virgin’s robe, and the pigment was identified as high quality coarse azurite using polarized light microscopy. Unfortunately, the robe appears much darker and less three-dimensional than it would have been when first painted. As often occurs with azurite, the paint has discoulored from aged medium and varnish, and the paint layer has suffered abrasion from past restoration treatments. When initially painted, the robe would have been a bright blue and would have appeared to drape more realistically: examination of the painting using infrared reflectography (Fig. 2) revealed extensive underdrawing in a liquid medium, and folds in the robe were both underdrawn and possibly outlined with carbon-containing black paint.

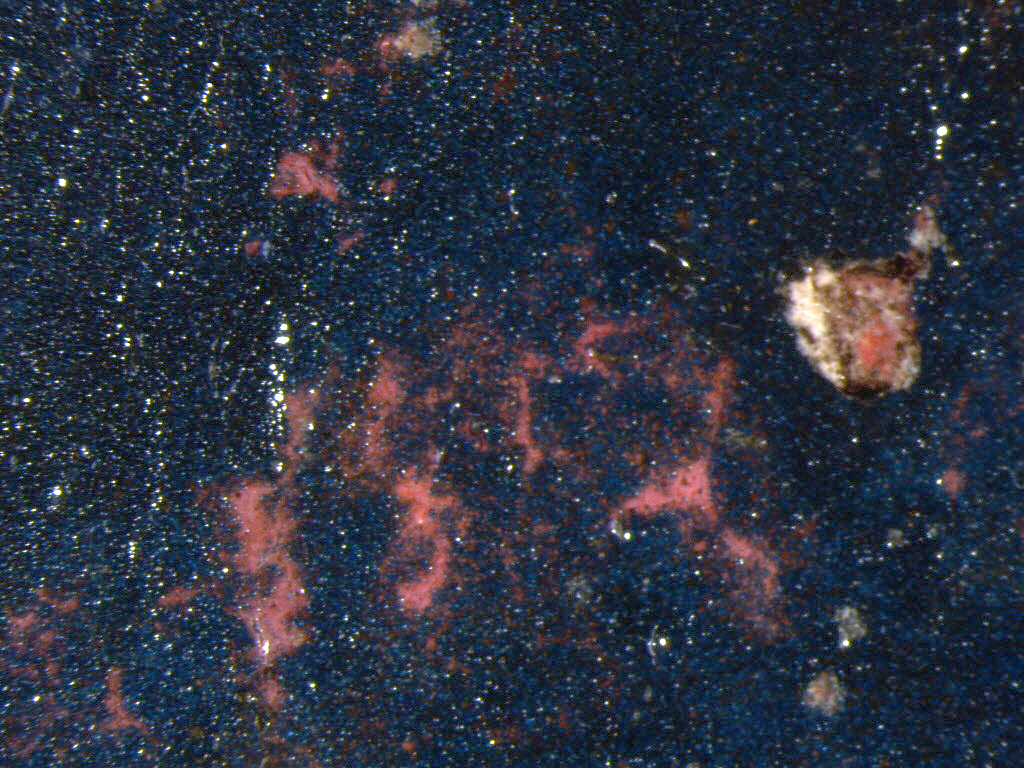

Perhaps the aspect of Pinturicchio’s technique I found most intriguing, however, was his method of underpainting. Microscopic (Fig. 3) and cross-sectional analysis of the paint layers in the Virgin’s robe revealed a locally-applied pink underlayer. John Brealey, the paintings conservator who treated the painting previously, estimated this layer to contain madder – a red lake – although analysis was not undertaken to confirm this identification. This underlayer does not seem to have been modelled to any significant extent, since the radio-opacity in the X-radiograph is quite even.

The purpose of a pink or red underlayer in the mantle would have been to warm the resulting hue once the blue paint had been applied, as azurite can sometimes appear greenish. As Christine Kimbriel and Youjin Noh explore in “Sebastiano del Piombo’s Adoration of the Shepherds: On the Pursuit of Colouristic Splendour in a ‘Lost’ Painting,” it was not uncommon to find blue over pink or red underlayers in fifteenth-century and early sixteenth-century Venetian painting.1 Kimbriel and Noh cite examples of paintings by Giovanni Bellini, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Giorgione with this type of layering.

In contextualizing Pinturicchio’s use of this type of layering, it became clear that there are extant examples of works containing underpainting of lead white and red lake underneath blue robes or sky from as early as the fourteenth and fifteenth century, including paintings by Giotto.2 Raphael, who came to prominence only a generation after Pinturicchio, is perhaps the best-known example of a central Italian artist using this method.3

Additionally, this type of layering was a common technique in the painting of frescoes. For example, a layer of red ochre underlies azurite pigment in Perugino’s The Circumcision of the Son of Moses in the Sistine Chapel.4

While the presence of this pink layer in Pinturicchio’s Virgin and Child was initially surprising, it became apparent through research that the artist’s technique follows a tradition of employing pink and red underlayers under blue for optical purposes.

Elisabeth Petrina, 1st year student, used the information and reconstructed this painting with historically-accurate materials.

Treatment History

It is not often that documents recording the historic treatment of paintings exist, but when they do, they can afford the opportunity to reflect upon past conservation practices and study how specific restoration materials have aged. This was found to be the case with Virgin and Child, which was previously treated by John Brealey (1925-2002) in 1964. Brealey was a prominent figure in the history of paintings conservation, and his ideas and philosophies have had long-lasting significance for the field. He was a member of the advisory council of the Hamilton Kerr Institute at the time he treated this painting, and he left London in 1975 to become the chairman of paintings conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The treatment report and photographs of Virgin and Child indicate that a good deal of previous restoration was removed by Brealey, but some old retouching and gilding was left. In Brealey’s words, “The gold hatching indicating the highlights is bogus, but has been left on because there must have been something similar on originally.” The thinking described in the treatment report is in line with Brealey’s well-known philosophy of selective cleaning. Ultraviolet examination of the painting (Fig. 4) confirmed that retouching from at least two campaigns of restoration were still present: Brealey’s and at least one previous restoration.

Significantly, the report also specifies that the painting was revarnished with MS2A®, MS2B®, and wax. Both of the MS2® varnishes are ketone resins, with MS2B® having a slightly different solubility and higher viscosity.5 The identification of these coatings accorded with their appearance, since synthetic varnishes can have a tendency to grey and dull rather than yellow like natural resin varnishes (Fig. 5). Knowing the materials used to varnish the painting allowed testing of the theory that the coatings should remain easily reversible over time. While they were certainly still soluble, organic solvents of a surprisingly high polarity were required in order to remove the conservation varnish.

Treatment

In spite of the unexpected polarity of the synthetic coating, varnish removal was relatively straightforward except for within the Virgin’s blue robe. The coarse azurite in this area was found to be under-bound. This means there was a higher ratio of pigment to oil, not sufficient to fully coat the particles and bind them into the polymerised oil network. Contrary to the rest of the painting, the robe was cleaned using a quickly evaporating solvent on cotton swabs, lightly rolled over the surface, in order to solubilize and reduce the varnish without excess mechanical action.

Significant amounts of overpaint and chalk fill material had been left covering original paint, so treatment also involved reducing these foreign materials under the microscope (Fig. 6). Additionally, discolored brown material within the halo was reduced using aqueous solutions and gels.

Unfortunately, I was unable to complete the treatment prior to finishing my post-graduate internship in the summer of 2016. The filling, retouching, and revarnishing were carried out by the Hamilton Kerr Institute’s Director, Rupert Featherstone (Fig. 7).

Although I would like to have seen this treatment from start to finish, I learned a great deal from the opportunity to study this artwork. I hope this text provides some insights into the creation and history of the work, and that you will visit the Fitzwilliam Museum to see Virgin and Child for yourself!

Kari Rayner, 2nd year Post-Graduate Intern (2015-2016)

About the Author:

Ms Kari Rayner holds a Master of Arts in Art History and an Advanced Certificate in Art Conservation from New York University, USA. She also graduated with her Bachelor of Arts in Art History, Art Theory and Practice from Northwestern University, USA. During her graduate studies, Kari interned at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne and worked at Modern Art Conservation in New York, NY. Her final-year internship was undertaken at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and she completed a year-long post-graduate internship at the Hamilton Kerr Institute from 2015-2016. Kari returned to the NGA in the fall of 2016 as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Paintings Conservation.

To contact Kari: rayner.kari.s@gmail.com

Notes

1 Kimbriel, Christine and Youjin Noh. “Sebastiano del Piombo’s Adoration of the Shepherds: On the Pursuit of Colouristic Splendour in a ‘Lost’ Painting.” In Artists’ Footsteps: The Reconstruction of Pigments and Paintings: Studies in Honour of Renate Woudhuysen-Keller. S.l.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2013.

2 Sincere thanks to Elizabeth Walmsley of the National Gallery of Art, who shared her expertise in Italian painting and directed me to the following resources on the topic of pink/red underlayers. Borgia, Ilaria, Diego Cauzzi, Bruno Radicati, and Claudio Seccaroni. “Raphael’s Saint Cecelia in Bologna: New Data about its Genesis and Materials.” Raphael’s Painting Technique: Working Practices Before Rome. Proceedings of the Eu-ARTECH workshop. Eds. Ashok Roy and Marika Spring. Page 95

3 Ibid, page 95

4 Santamaria, Ulderico and Fabio Morresi. “Perugino’s technique in the Sistine Chapel: scientific investigations.” The Painting Technique of Pietro Vannucci, called Perugino: Proceedings of the LabS TECH Workshop. Eds. Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti, Claudio Seccaroni, and Antonio Sgamellotti. Pages 99-100

5 “Low Molecular Weight Varnishes.” Ed. Wendy Samet. Paintings Specialty Group Wiki, 1997. Web. Accessed June 4, 2017. http://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/IV._Low_Molecular_Weight_Varnishes