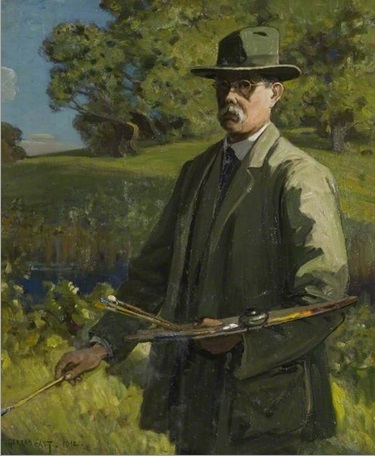

It is without a doubt that the artist Sir Alfred East (1844-1913), who was inspired by the Barbizon School, enjoyed the interest of the 19th century public.[1] The Times, for instance, referred to him on more than 500 occasions, and printed 11 bulletins describing his fluctuating condition in the month before he died.[2] Amongst various honours on a national and international scale bestowed on him, he was elected president of the Royal Society of British Artists (a post he held from 1906 until his death), received the status of Royal Academician (1913) and was awarded a knighthood by Edward VII (1910), but has since regrettably fallen into obscurity. Despite a slow start to his career, he was commissioned by the Fine Arts Society, to record the landscape of Japan over the course of a year. Subsequent travels he embarked on throughout his career to Europe and America yielded a vast collection of drawings, etchings and paintings in oil and watercolour. Before his death in 1913 East initiated the construction of the Alfred East Art Gallery in Kettering, Northamptonshire, that received a generous amount of his works.

It is from this gallery that two of his paintings, namely Midland Meadows and Lake Bourget from Mont Revard, France, arrived to the Hamilton Kerr Institute for conservation treatment. The discoloured and disfiguring varnish layer on both paintings, was identified as the main reason for the conservation treatment, although structurally sound, standing as a testament to his sound painting technique. Before the treatment of any painting, it is useful to conduct research about the artist and his painting technique, since it can often give an indication of the materials used by the artist. Nineteenth-century paintings in particular, frequently exhibit experimentation with media and layering that might give an unexpected and inconsistent response to the commonly used solvents for cleaning. Fortunately, in this case, the artist himself was rather keen on sharing his skill of landscape painting and how ‘to get the spirit of’ nature captured in a picture. [3] East wrote and published The Art of Landscape Painting in Oil Colour, his own guide to landscape painting, in 1906.[4] This manual explains his painting technique, and even mentions the pigments found on his palette, including the exact tube sizes. Thus it unsurprisingly formed an invaluable source for the treatment of the paintings.

From his writings it appears that he adopted a well established three-stage-technique that makes use of an under-painting, another layer concerned with the correction of values, and a final stage for the addition of details; all painted with lean oil paint. During this process he practically repainted the entire canvas after the first layer and then proceeded to pick out isolated sections that required further reworking and detail. In doing so, some parts of the second layer that were not reworked in the last stage, and are now part of what is visible in the version we see today. An example of such an area is the fold over edge of Midland Meadows that shows trees reaching higher in the previous layer.

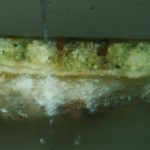

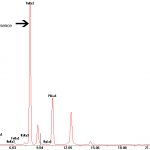

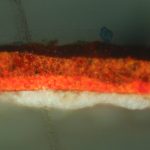

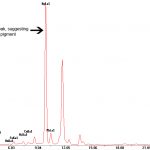

Between the individual layers, East added medium (or binder) to saturate his lean oil paint layers – a process also known as ‘oiling out’. [5] Favoured particularly in the 19th century, this method used a cloth dipped in a medium of choice (- poppy seed oil for East), and rubbed into the dried paint, before the next paint layer followed. Some cross sections of the painting appear to show a layer that might be identified as such, with a characteristic absence of pigment and ultraviolet light quenching that is to be expected (not pictured in this article).

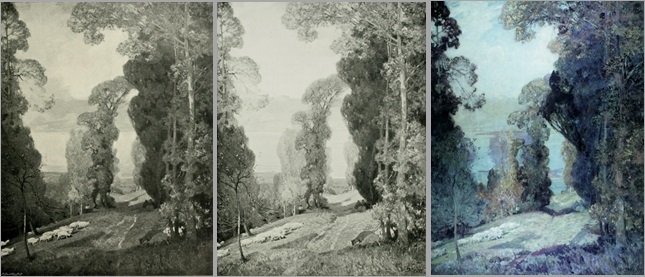

Not only is it possible to see proof of East’s described painting technique in his paintings, but Lake Bourget also reveals a significant compositional change by the artist that must have happened more than six years after it was first exhibited in 1900. Since the painting did not sell during the Royal Academy Exhibition, East may have been inclined to rethink his composition after a critic of his painting found that ‘his trees have had so much of the reality abstracted out of them that they cease to be interesting.’[6] An image of the same painting published in his manual in 1906 shows no changes. The first instance of alterations was registered by the Alfred East Art Gallery in Kettering who received the painting directly from the artist for their opening exhibition in 1913. There is little doubt that East’s reworkings happened before the painting arrived to the Gallery. In ultraviolet light it is also possible to ascertain some of the less visible passages he revisited, since they lie above the oiling out layer and therefore appear darker.

These areas also directly correspond to the passages that exhibited solvent sensitivity during cleaning. East’s described use of lean oil paint suggests that his mixtures were under-bound, meaning the pigment particles were not sufficiently coated with binding medium and therefore friable. Consequently the varnish covering sensitive areas was merely reduced and a thin layer was left in place.

After surface cleaning the decision to remove the discoloured varnish layer was supported by the fact that it reached into ageing cracks and losses, which means it is less likely that it was applied by the artist. Visually this layer also distracted from the composition with its drip marks in the sky. In order to remove the varnish, small test areas in different coloured passages, were opened up to establish the best mixture of solvents for cleaning without affecting the paint layers. Usually the sensitivity of a paint layer corresponds to a specific colour or medium used in a passage. However, this was not the case in East’s paintings since the solubility appeared to be caused by underbound final paint dabs of varying colour. After cleaning an isolating synthetic resin varnish was applied, which is less prone to yellowing in the future than its natural counterpart, and the few existing minor losses were filled and retouched. To protect the paintings from vibration and environmental influences a sailcloth stretcher-bar-lining was attached. Moving and lifting such a large scale object, required continuous help from everyone in the studio, and framing was no exception to this. The gilt frame was given a few alterations to house the painting more securely (see the Weston Park in-situ post for more information) before the painting and frame were wrapped and transported back to the Alfred East Art Gallery in Kettering.

During the research for this project it was also possible to catch a glimpse of East’s meticulous character from his artist supplier account with Charles Roberson & Co, a 19th century colourman whose archive is housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute. When he was sent a selection of brushes from Roberson, East rejected the majority; perhaps because they didn’t meet his standard.[7] He also appears to have repeatedly bought similar items from Roberson, suggesting that he may have had several specific colourman for different types of supplies.

Spending long hours in front of a painting the colours, lines and brushstrokes of the artist become very familiar. This direct contact with the painting was only furthered by the information that was gained about this artist and his technique, and made the treatment all the more interesting. Do visit the Alfred East Art Gallery in Kettering to see the actual paintings in their original exhibition space (due to their changing exhibitions it is best to inquire before a visit if the paintings are currently on display).

Michaela Straub, 3rd year Student

Bibliography

[1]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=05C02RhJZCkC&pg=PA360&lpg=PA360&dq=alfred+east+benezit&source=bl&ots=QKqmf09Oc5&sig=VU5GADli_TXiXvMjTq44kEfW0_A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZ9eCVx5vQAhWsB8AKHTUqDv0Q6AEIQTAK#v=onepage&q=alfred%20east%20benezit&f=false and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_East

[2]J Paul & M Kenneth, Alfred East Lyrical Landscape Painter, Bristol, 2009.

[3] J Paul & M Kenneth, p. 25.

[4] A East, The Art of Landscape Painting in Oil Colour, London, 1906. Further publications after his death include: E Bale & A East, Brush and Pencil Notes in Lanscape, London, 1914.; A East, H Cortazzi & Japan Society (London), A British Artist in Meiji Japan, Brighton, 1991.

[5] Oiling out is mentioned by several other artists such as George Frederic Watts in Watts, M. S. 1912. George Frederick Watts, London; Gilman Harold (a new way of working that doesn’t involve oiling out) http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/sarah-morgan-joyce-h-townsend-stephen-hackney-and-roy-perry-canvas-and-its-preparation-in-r1104353; Lord Leighton (in a letter to Prof. Church he writes about using rectified petroleum instead of the normal process of oiling out) and is mentioned Leighton’s Painting process forms from the Royal Academy noting that for Daphnephoria he used Roberson’s medium for ‘rubbing in’.

[6]The Spectator no. 3750, 12 MAY 1900, p. 18 http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/12th-may-1900/18/art

[7]Roberson Archive: MS 121-1993, p. 197; MS 313-1993, p. 88.

About the Author:

Currently in her third year studying easel painting conservation at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, Michaela Straub graduated from Aberystwyth University with a BA in Fine Art and Art History in 2012. She has undertaken internships in private studio’s, the Denkmalschutzamt in Germany and the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna.

To contact Michaela Straub: straubmich@aol.com