Once in a while, an artwork is not only aesthetically or structurally improved during treatment – it is completely transformed. This is the case with a privately owned painting treated during 2015 (Fig. 1).

Formerly attributed to Leonardo Coccorante (1680-1750), the ostensible subject of the painting corresponds with the eighteenth-century fashion for scenes of Roman ruins. The work depicts a pastoral landscape featuring crumbling ancient columns, with the skyline of a city in the distance highlighted by the setting sun.

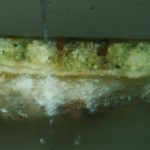

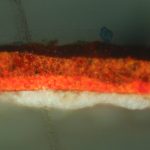

When the work arrived at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, an incredibly thick, discolored varnish and heavy layer of grime obscured the scene. Examination with ultraviolet light did not reveal the extent of previous restoration. During cleaning, it started to become astonishingly clear that the entire sky and city in the distance had been overpainted. Many of the buildings in the distance had been completely invented, as was the sunset. Removing the previous restoration uncovered red and yellow shooting flames in the background – in fact, the entire city was ablaze. Additionally, the figures in the foreground had been altered. The blue-robed figure was not a shepherd, but rather an angel: the staff the figure carried was a later addition, and the figure’s large, white wings had been hidden by overpaint.

These discoveries led to the reassessment of the painting’s subject matter after treatment (Fig. 2). The most plausible identification of the narrative, given the newly manifest iconography, was that of the biblical account of Lot. The Book of Genesis describes how angels warned Lot of God’s imminent destruction of the cities of Sodom. This allowed Lot, his wife, and two of his four daughters to escape. However, the other two daughters and their husbands refused to flee and thus perished. In grief, Lot’s wife looked back towards the burning city and turned into a pillar of salt. Accordingly, in the painting, there is a small white figure in the background. The scene depicted in the painting follows this narrative remarkably closely, except that it pictures four young women (instead of only two daughters) at the far left. One possible explanation is that two of the women are Lot’s daughters, and two are angels leading them to safety; however, the worn condition of all four figures makes it difficult to distinguish any wings or otherwise characteristic features.

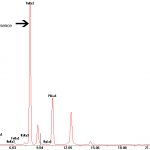

The attribution to Leonardo Coccorante was also called into question because of the painting’s drastic alteration. While famous for his dramatic scenes of ruins, Coccorante is not known to have depicted biblical subjects. It was hoped that technical analysis would clarify the painting’s dating or region of origin. The work was analysed using X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy to detect the elements present within the paint and, therefore, infer the presence of various pigments. Dispersed pigment samples were also taken and examined with polarized light microscopy. The range of pigments identified unfortunately does not point to a specific geographic location or time period, but considering the painting’s other physical characteristics and stylistic attributes, the work most likely dates to the seventeenth or eighteenth century. This means that we cannot confirm or rule out Coccorante as the author and that other attributions should still be considered. François de Nomé (1593-1620) stands out as a particularly plausible alternative possibility: this French painter was based out of Rome and later Naples, and his dramatic scenes of ruins tend to deal with disastrous mythological or biblical narratives. In this sense, an attribution to this painter is perhaps more credible than that of Coccorante, though this text declines to make any definitive assignment.

Treating this painting was a rich experience and necessitated close consultation with the work’s owner. The treatment itself, the details of which are beyond the scope of this post, was challenging in that it required using various approaches to overpaint removal. Additionally, the heavily abraded state of the painting (which likely factored into the reason for overpainting in the first place) as well as a large loss in the lower right corner, necessitated difficult decisions regarding the appropriate extent of retouching. The transformation of the painting during treatment leaves lingering questions as to the work’s circumstances of creation and the identity of the painter.

One day, perhaps, these mysteries will be solved.

Kari Rayner – 1st year Post Graduate Intern at the Hamilton Kerr Institute

Ms Kari Rayner graduated with a Master of Arts in Art History and gained an Advanced Certificate in Art Conservation from New York University, USA. She also has a Bachelor of Arts in Art History, Art Theory and Practice from Northwestern University, USA. During her graduate studies, Kari interned at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne and worked at Modern Art Conservation in New York, NY. Her final-year internship was undertaken at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and she will be returning to the NGA in fall 2016 to begin an Advanced Fellowship in Paintings Conservation.

To contact Kari Rayner: rayner.kari.s@gmail.com