Kate Waldron, Jo Neville and Rowan Frame

Thank you for joining us for the second blog post sharing our experiences of a study trip to Italy in July 2019! Following the format of our itinerary in Rome, this part of the trip involved visits to further renowned schools and institutions of conservation in the city of Florence, meeting yet more lovely and inspiring people who were pleased to share their work with us – and finding windows of extra time to pop into a beautiful church or two. Without further ado we will pick up where we left off, arriving in Florence for a busy, exciting and incredibly hot two days…

Thursday, 18th July 2019

Visit to the Studio Arts College International (SACI) – Jo

On the morning of our third day, we paid a visit to the Studio Arts College International (SACI). SACI is housed in a Renaissance palazzo in the centre of Florence. Stepping into the building, we could hear voices of chattering students echoing through arched hallways. In many ways, this visit offered interesting comparisons to our own department. SACI was founded a year after the Hamilton Kerr Institute, and also offers a diploma course in the conservation of paintings.

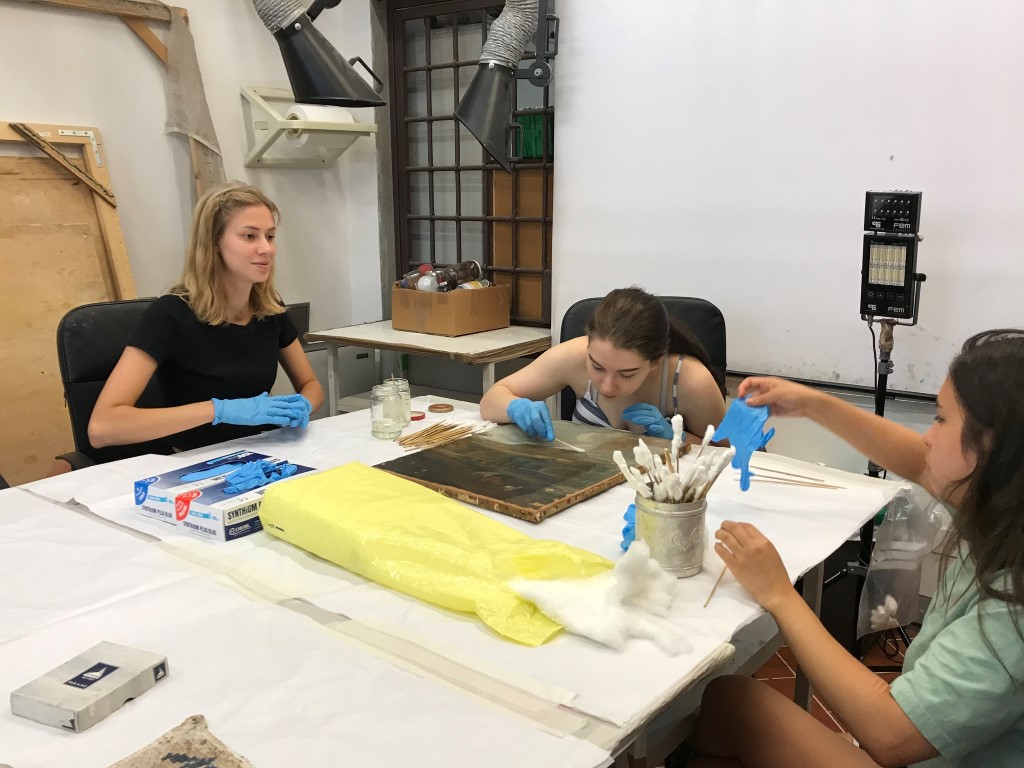

Over coffee, we were able to talk to current conservation students, and had lively discussions about their training and projects. It was clear that the SACI diploma course has an international reach, with many students having come from the U.S. We learned that in situ work is a very central aspect of their training, with an impressive range of projects undertaken both in Florentine churches as well as further afield.

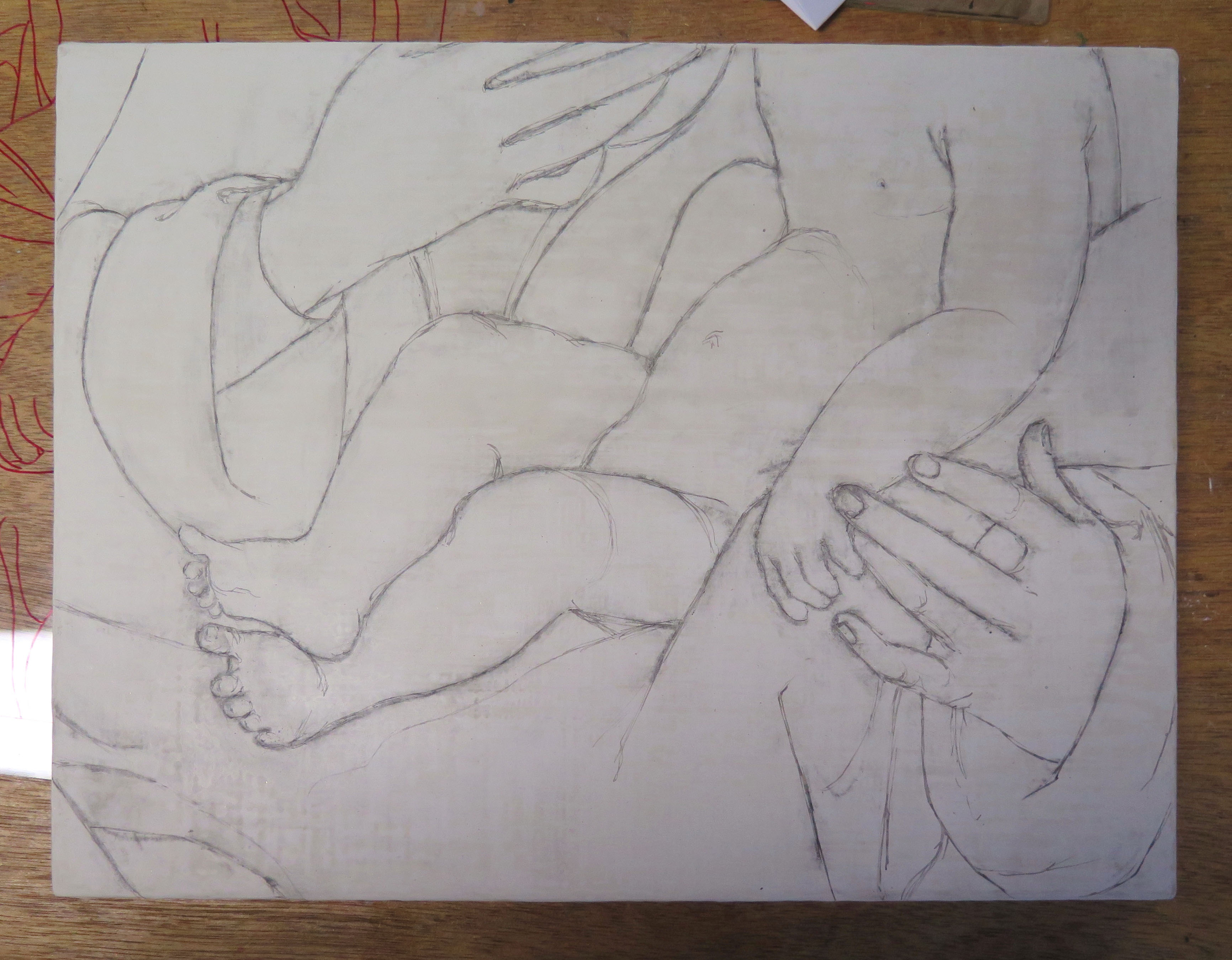

We were then given an extensive tour of the studios by the head of department, Dr. Roberta Lapucci. We saw paintings that presented a wide variety of conservation challenges, and discussed similarities and differences to the conservation practices commonly employed at our own studio. For retouching, we noted the diverse shades of brown on retouching palettes, leading to a fascinating comparison of Italian and British approaches to the question of patina on paintings. There were also many familiar sights: Rowan and I were pleased to see the reconstructions made by SACI conservation students, which looked very similar to those that we had completed earlier in the year.

To round off the visit, we were given a tour of the archaeological conservation studio with Dr Nora Marosi, and introduced to some of the current projects. This included a very interesting discussion about the central role of the soprintendenza (the Ministry of Arts and Cultural Heritage) for conservation decisions concerning all objects that belong to the Italian State, and about some of the regional differences in choice of materials and techniques for certain conservation treatments. We were also shown some amazing 3D-printed replicas of objects for display (pictured).

Visit to the Opificio delle Pietre Dure – Rowan and Kate

In the afternoon, we reconvened at the Opificio delle Pietre Dure e Laboratori di Restauro (OPD). We were greeted by Marco Ciatti, director of the laboratory and of the higher education school of training for conservator-restorers at the Institute, where he is teacher of the history and theory of conservation on the 5-year programme (established in 1978). Marco gave us an engaging introduction to the Institute and its part in the history of conservation in Florence, from the time of Vasari to the catastrophic flood of 1966. It was at the time of the flood that the Opificio relocated from the Uffizi to its present location in a striking building that used to be a military fortress. When the Italian government formed a Ministry of Cultural Heritage in 1975, the restoration laboratory of the soprintendenza was merged with the OPD under the directorship of Umberto Baldini, to form a National Institute of Conservation, and today the Institute receives artworks from all over Italy including paintings, sculpture, textiles, works on paper, mosaics, jewellery, and objects of terracotta and stone.

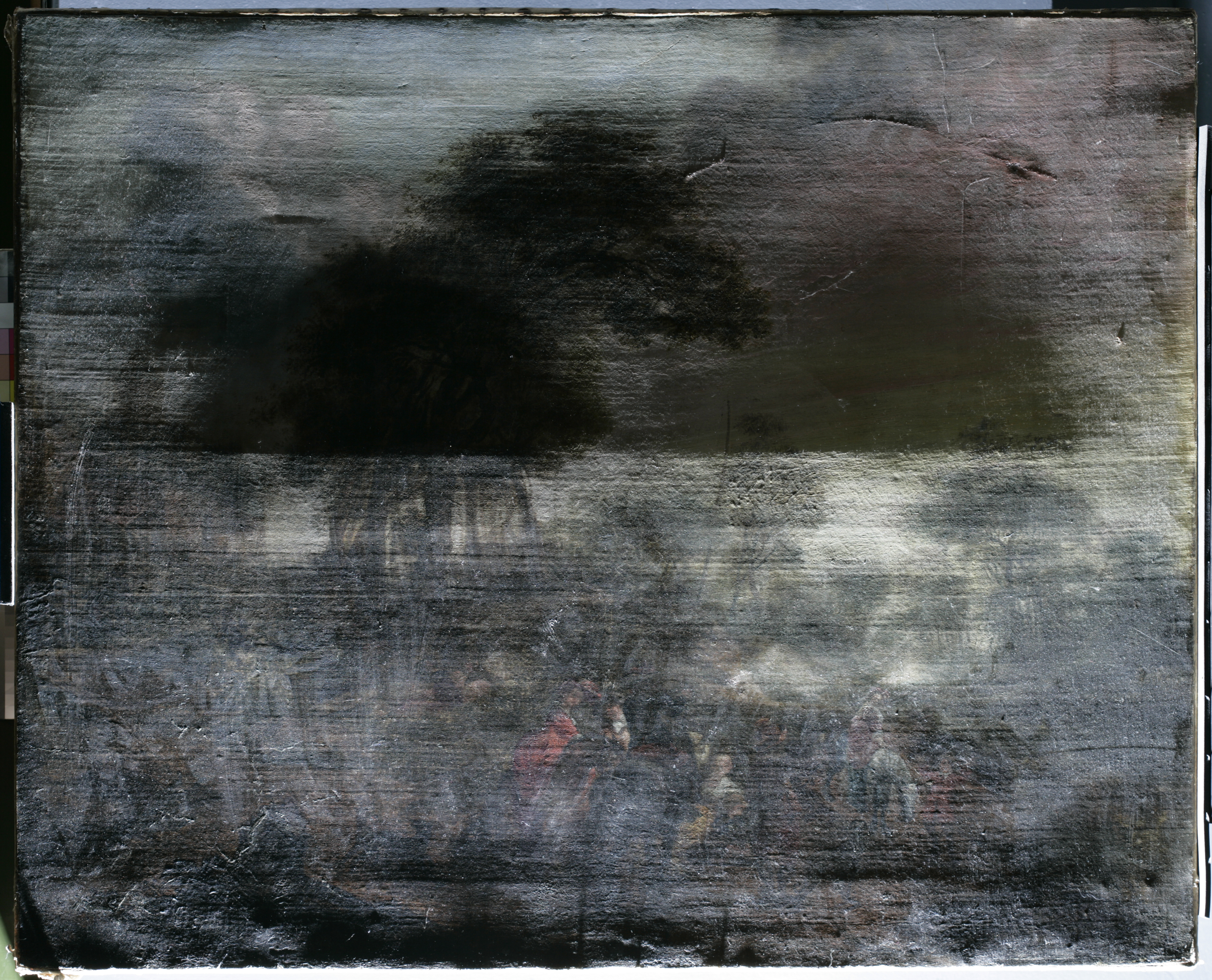

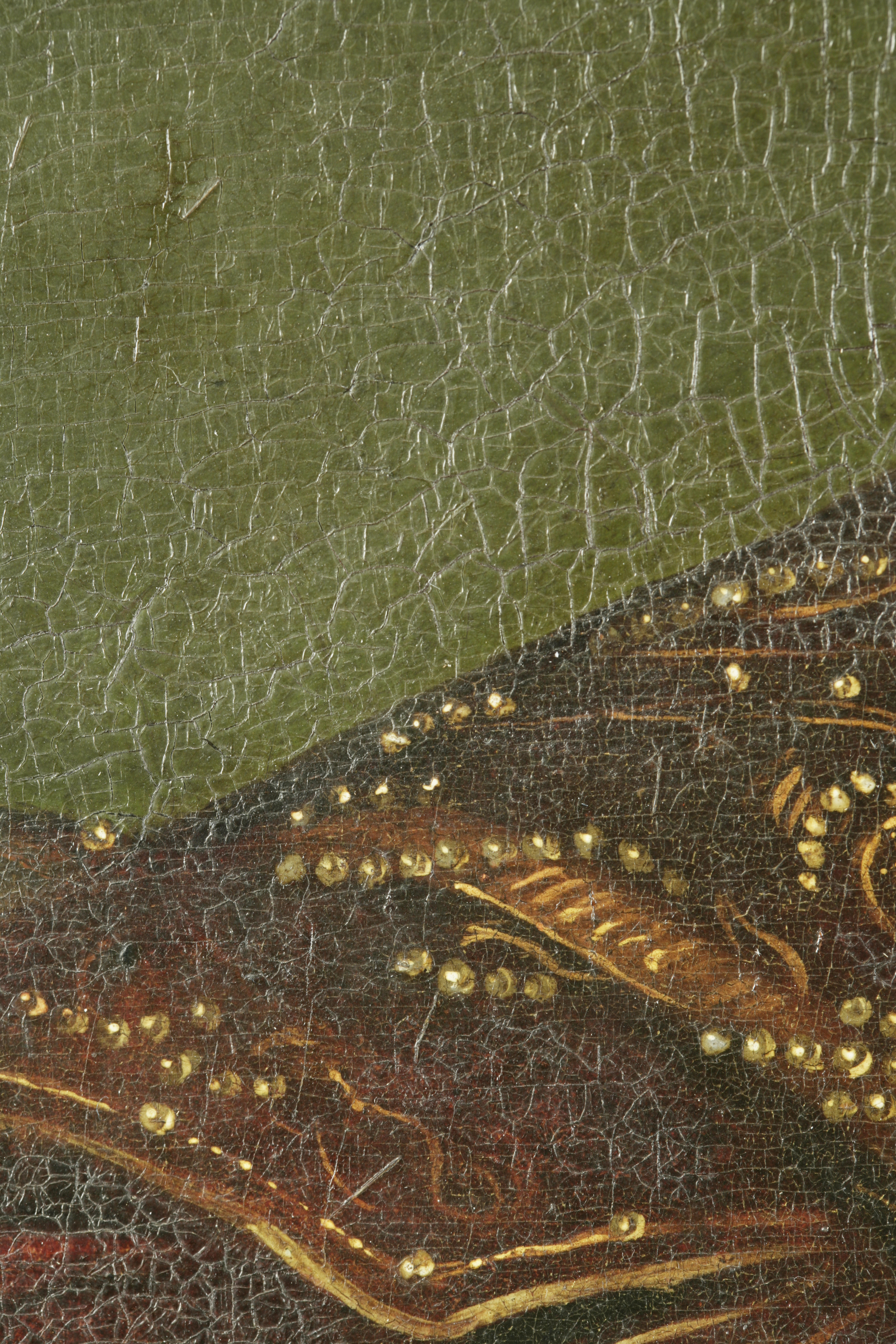

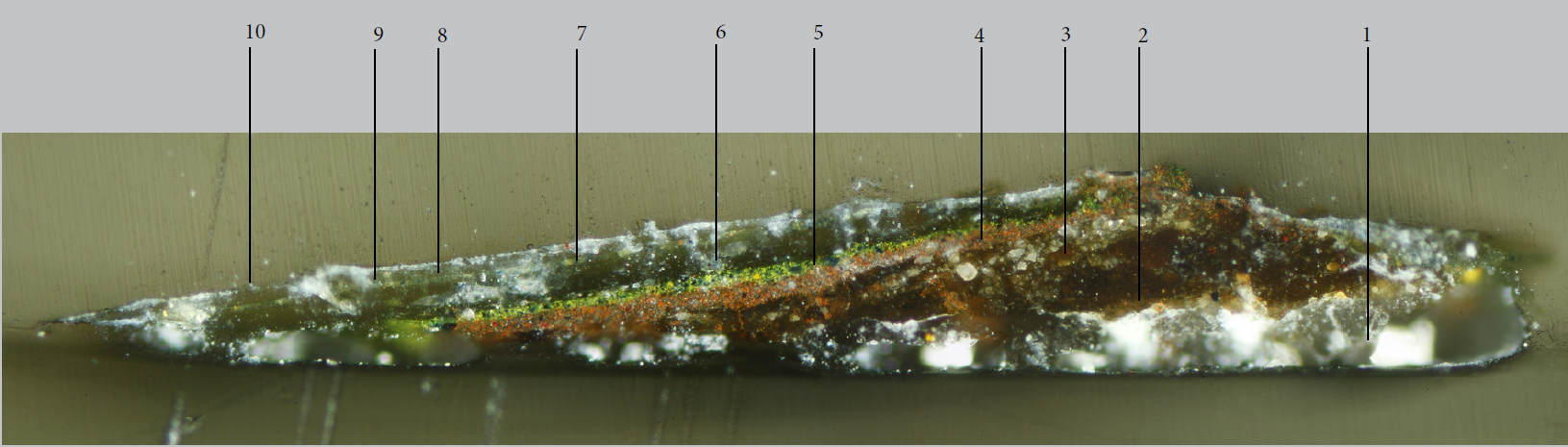

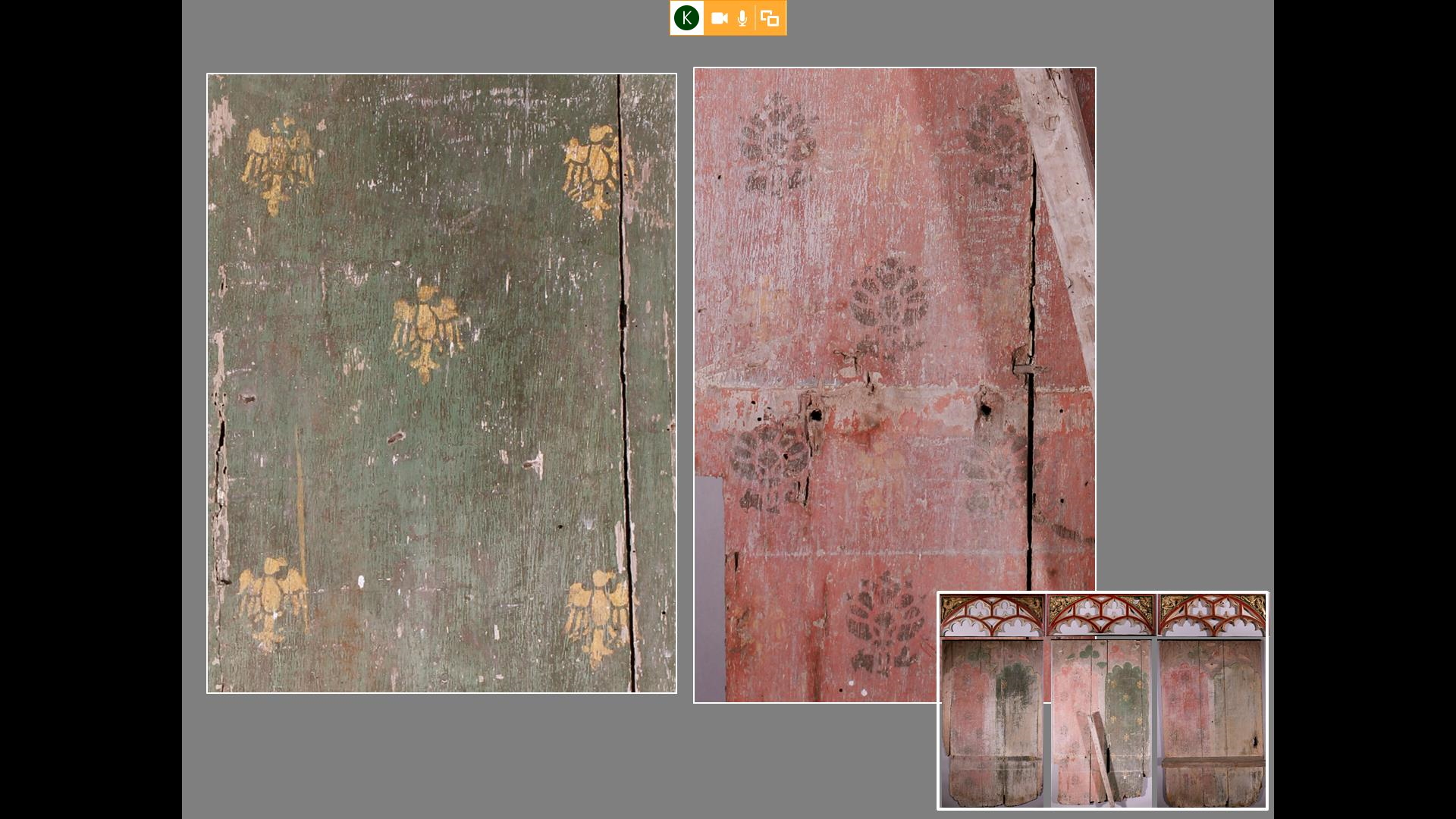

The Opificio prides itself on being a renowned centre of research as well as restoration and training, and there is a strong specialisation in the conservation of paintings on panel. The enormous building is divided into areas focusing on selected aspects of conservation treatment, with, for example, a whole room dedicated to working on the paint layers. We were given a tour of the institute and moved from painting to painting, in each case hearing from Marco about the analysis or treatment undertaken and enjoying the opportunity to admire the beautiful artwork and discuss the artists. Many of the paintings return to churches so it was interesting to hear about the questions and procedures involved for preparing them for those environments. Like the HKI, Marco emphasised that the OPD is open to researching new methods and technologies under development for conservation treatments and incorporating them into their practice.

One of the most exciting things was to hear about the expert, complex structural treatments carried out on a number of panel paintings in the studio, with techniques that were developed there and are the subject of continuing research and refinement: the OPD remains a centre of excellence globally for the development of solutions for structural conservation and support for paintings on panel.

It was an incredibly hot day, so after our visit we went as a group to enjoy some more gelato! The treat was kindly paid for by the members of Cambridge Arts Society, as a thank you after a visit they paid to the HKI earlier in the year.

Not forgetting Rupert, Vicky and Adèle!

Friday, 19th July 2019

Visit to the studio of Stefano Scarpelli – Kate

On our final day, we visited the private conservation studio of Stefano Scarpelli. Along a corridor lined with cabinets full of brightly-coloured pigments, we met Stefano and his son in their main studio space, and glimpsed other rooms beyond with forests of frames and paintings. Stefano studied conservation at the OPD and later taught the relining course there. Before that, he trained as a conservator under Professor Edo Masini, the former technical director of the paintings conservation lab at the OPD and a prominent Florentine conservator. Stefano later went on to collaborate with Masini and has worked for major galleries in Florence and elsewhere, and on high profile works of art by artists including Giotto, Masaccio and Caravaggio.

Mostly, Stefano mostly works for private collections and galleries, but the studio has worked for the Uffizi and other public collections. Although they are familiar with contemporary developments in conservation methods and materials, they always start with traditional methods and this is their preference, as they are familiar with the materials and how they age. Stefano and his studio undertake all of their own structural work and lining of paintings, and also the work on frames. It was fascinating to hear about Stefano’s experiences of lining paintings, especially in the context of changing attitudes and approaches to lining in Florence and Italy over the years. We were introduced to several paintings which will be lined in the studio, including a painting that was severely damaged by flooding in the church to which it belongs. We also learned of Stefano’s procedures for retouching: for paintings owned by the Italian State, trateggio (see previous blog post) is the only retouching technique that is accepted. For other works, imitative retouching is done instead, as we are accustomed to doing in the UK.

Some reflections…

We had such an enlightening tour of conservation studios in Italy, augmented by visits to the breathtaking art in some of Italy’s best galleries and churches. At the institutions we visited, I was particularly struck watching students retouching using the trateggio technique. We learn about this in our own training, but I have not ever used the technique myself and I had never seen it in action before. It was much more complex than I could have imagined and I was in awe of the speed and precision with which the students worked. We were also conscious of the differences in material choices between conservators at different institutions, some remaining attached to historical or traditional materials and others being more open to new technologies and methods. However, the constant and resounding message we received from the conservators we met is that it is the skill of application that is perceived as key.

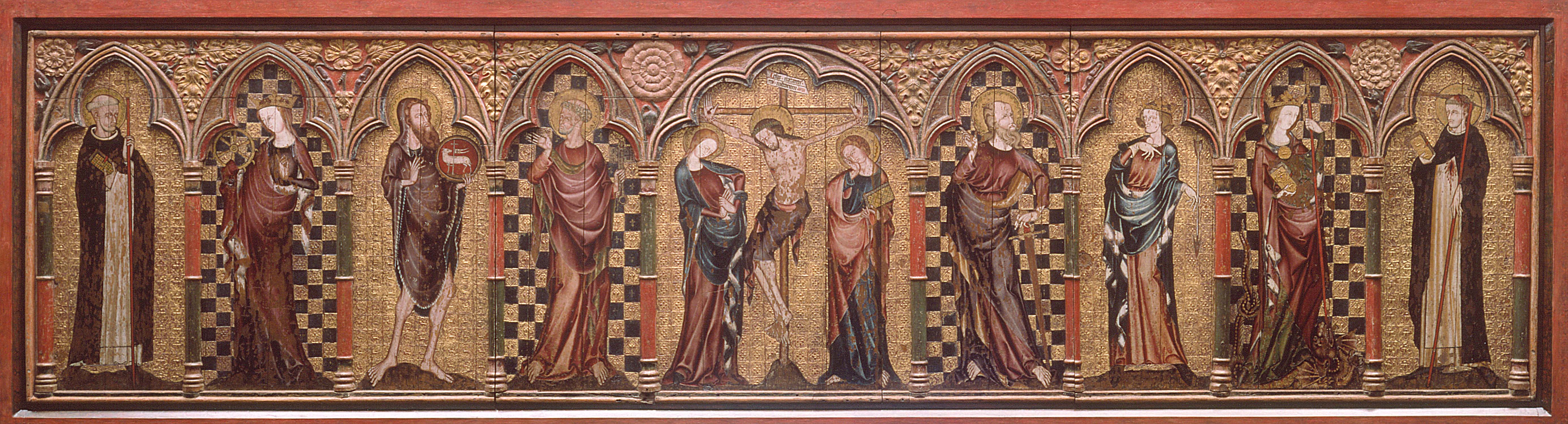

I want to end with a few thoughts from the final excursion of our time in Florence, on the afternoon of our last day before we returned home to the (rainy and cold) UK. We were treated to our very own private tour of the magnificent church of Santa Maria Novella, the main Dominican church in Florence, by Roberta Lapucci. It was my first visit to the church, yet it contains so many artworks that were central to my undergraduate art history studies and imprinted themselves in my memory. Roberta began with Masaccio’s groundbreaking Holy Trinity fresco, and told us about the process by which it was physically transferred from its unknown original location to its present position on the north wall of the nave, as well as other aspects of its conservation history. It was especially wonderful to hear about the technical art history of Giotto’s monumental crucifix, with emphasis on the skill of the carpentry and construction. I was particularly struck by the discoveries about the underdrawing: while the main composition is drawn freehand, the outline for the cross is known to have been provided by the church, and the faces of John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary are scored out according to ‘mask’-like models, called patroni, that would also have been imposed by the church. As we continued our tour of the church and cloisters, we also learned about some of the complex and devastating ways in which some of the frescoes have decayed over time or been damaged by ill-informed methods of cleaning in the past.

The visit to Santa Maria Novella served as a reminder to be thankful for every opportunity we have in our lives to experience direct close encounters with works of art. As events this year have shown, one can never know how long it might be before the next opportunity will arise – even if you work with art every day.

This two-day interdisciplinary conference, hosted by the Hamilton Kerr Institute and held at the Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, featured talks that explored how artists, conservators and their materials, ideas and techniques have crossed borders from antiquity to the modern day (click

This two-day interdisciplinary conference, hosted by the Hamilton Kerr Institute and held at the Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge, featured talks that explored how artists, conservators and their materials, ideas and techniques have crossed borders from antiquity to the modern day (click