For more stories from other conservation departments at the Fitzwilliam Museum, visit the Conservation and Collections Care blog!

This post was written last year by Alexandra Zappa, a former objects conservation intern in the Department of Antiquities. Alex graduated from UCL with an MSc in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums in 2012 and is currently working as a conservator in the United States.

One of the projects I was involved with since the beginning of my internship is the technical examination of a group of Ancient Egyptian inlaid eyes. The Ancient Egyptians used inlaid eyes in a variety of objects including statues, coffin masks, anthropoid coffins, in rectangular coffins and inlaid into the eyes of mummies.

The styles of inlaid eyes can range from appearing incredibly life-like to simply being a basic representation of an eye with a pupil. These differences could be a result of styles changing over time as well as the different uses to which inlaid eyes were being put. The Ancient Egyptians used a range of different materials to get their desired effect. Materials that have been identified in the inlaid eyes in the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collections include limestone, quartz, rock crystal, obsidian, bone and ivory, copper alloys, resin, plaster, animal glue and pigments.

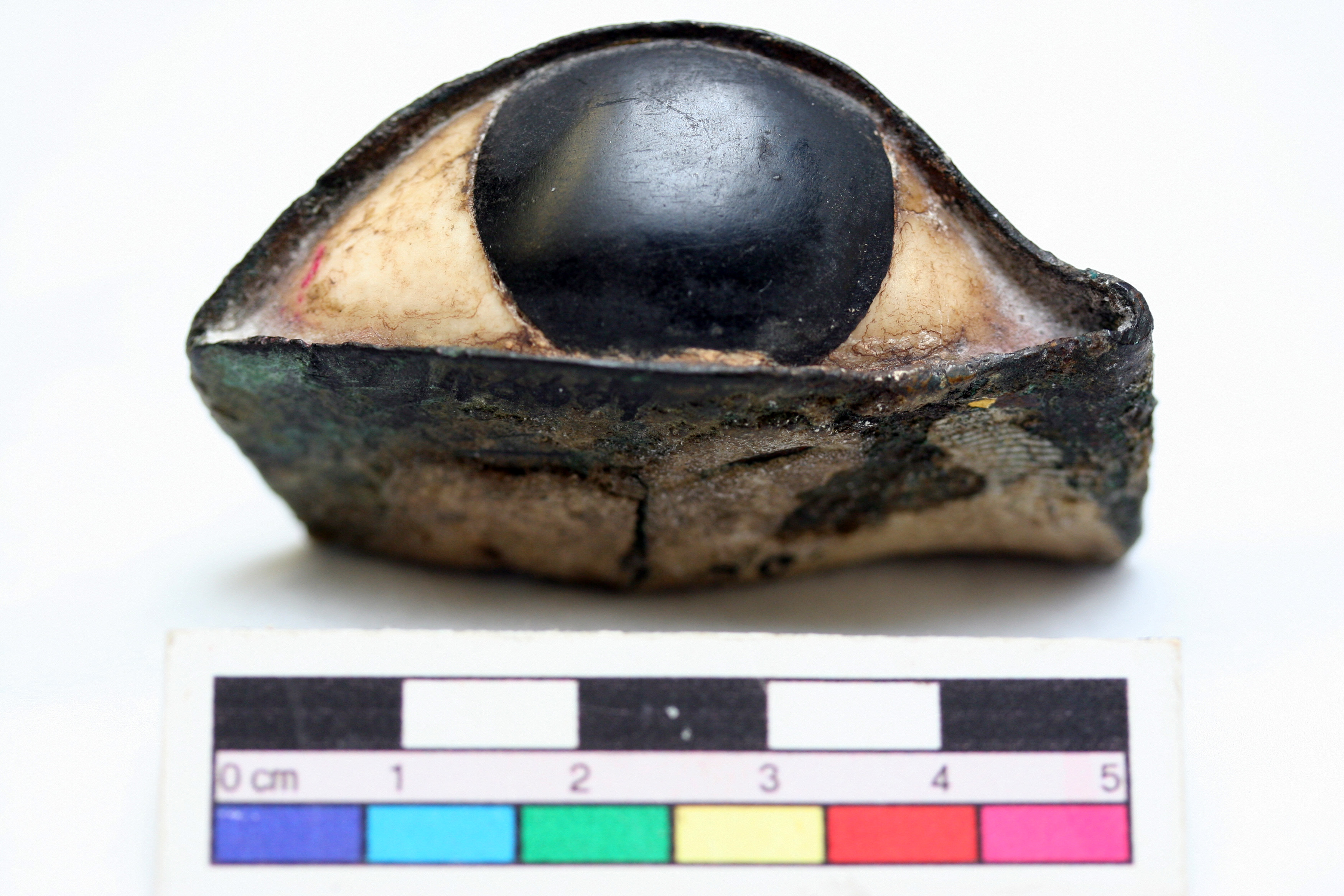

E.GA.4001.1943

One eye (E.GA.4001.1943) has been fascinating to examine as radiography has revealed some hidden details.

The eye came into the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1943 as part of a collection of over 7500 Ancient Egyptian antiquities that were presented to the museum by (Major) Robert Grenville Gayer-Anderson. A number of the inlaid eyes I have been examining are part of this collection and it’s been interesting to think about how Gayer-Anderson might have obtained these individual eyes during his time in Egypt.

This particular inlaid eye is made from a copper alloy frame, a quartz ‘white’ and a basalt pupil with plaster in the reverse of the frame behind the eye. When examining it initially under a microscope it was evident that the pupil had been inlaid into a hole carved, or drilled, in the front of the white and these two pieces had then had a copper alloy frame wrapped around them. The frame was made from a single sheet of copper alloy, which had been folded at the inner corner of the eye and bent to its current shape around the white. Plaster on the outside of the frame seems to indicate that this is what was used to anchor the inlaid eye into its socket.

There are also traces of gold leaf on the frame and near the pupil, which suggests that the eye once belonged in a gilded face.

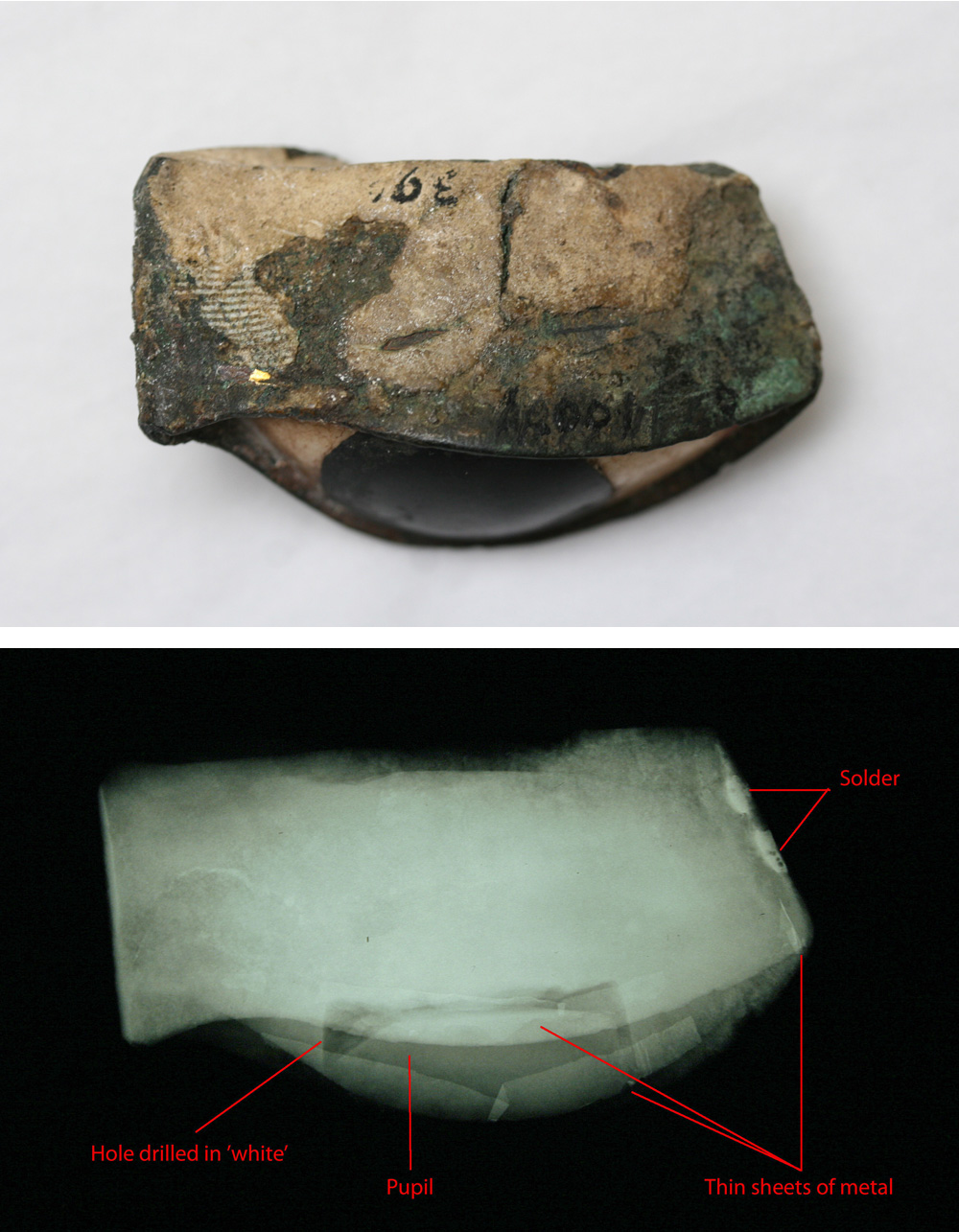

Radiography

Further details about how the eye was constructed were revealed when the eye was x-rayed.

You can see in the right side of the x-ray image above that the two ends of the copper alloy frame are held together with a solder, or two drops of metal, on the inside edge of the frame. This was something that was not apparent from the outside.

There are also two thin sheets of metal in between the frame and the top and bottom of the eye as well as a possible third small piece of thin metal on the outer corner of the frame. This metal is again not visible on the outside of the frame and it’s possible this was inserted to try to fill a gap between the eye and the frame to make the white fit more securely.

From the x-ray you can also see the shape of the basalt pupil and the hole in the white that was made to receive it. The hole is relatively uniform, with straight sides and flat base which could indicate that the hole was drilled. The basalt pupil, on the other hand, is uneven in profile and does not fill out the hole made for it.

While it can’t be said for certain what type of face the eye would have originally been inlaid into (whether it was in an anthropoid coffin or a mask, for example) some interesting details of its construction have been revealed as a result of further examination.

Conservation

This eye is in good condition overall. It won’t require any conservation treatment but it will likely be stored in the Museum’s Bronze Reserve. The Bronze Reserve is an environmentally-controlled store for objects that can benefit from being stored at a lower relative humidity. Metals like copper alloys can corrode in the presence of moisture and by storing the inlaid eye in the Bronze Reserve, this is a way to help prevent deterioration of the metal.

The examination of this object has been just one example of the exciting work I have been involved with and I’m looking forward to working on many more projects as my internship continues.

– Alex

I found this article very interesting and have made reference to it on my website as an amateur enthusiast and reader of ancient history and technology. An interest that evolved unexpectedly in recent years. I was reading up on the use of quartz in ancient history, on this occasion the eyes used in statues and found your article and blog on a Google search. I hope you won’t mind that I have referred to it and have taken the liberty of reproducing some of the photos. If you’d like me to remove them, I will upon request.

You’ll find my article here at the moment of writing though it is not finished and its title/page may change when ready – http://www.quantumgaze.com/ancient-technology/eyes-early-egyptian-statues/

Many thanks, Ian