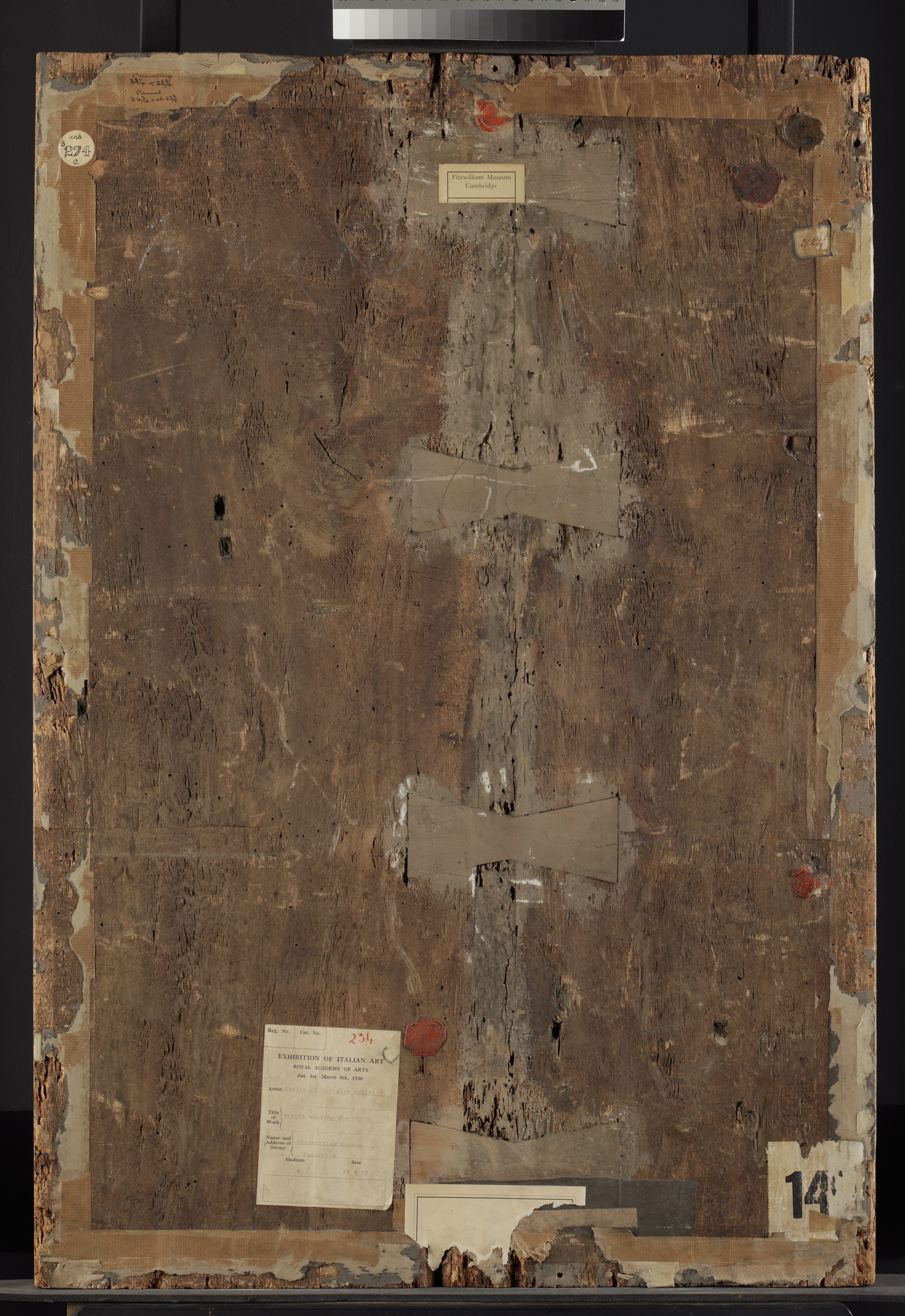

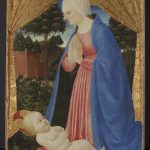

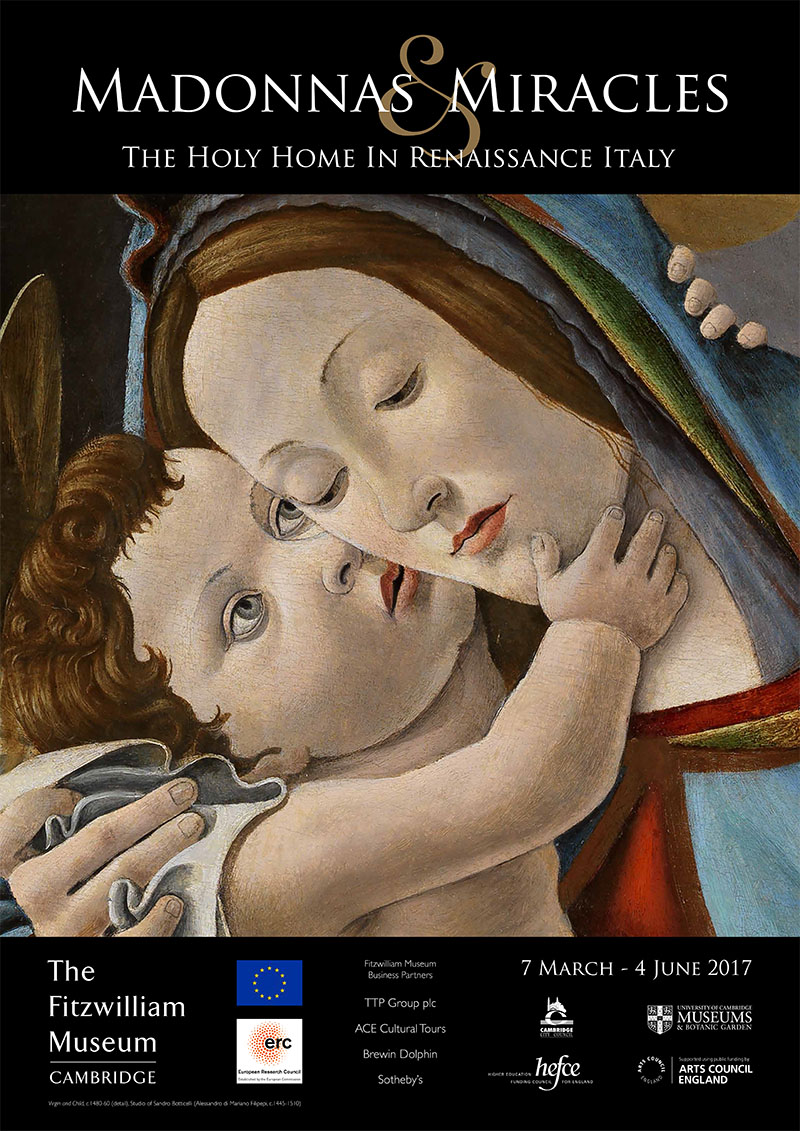

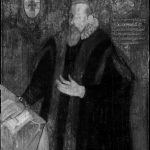

This oil painting on oak panel representing Elisabeth de Valois is a copy of the famous portrait originally painted by Anthonis Mor (c. 1517-1577), a Netherlandish portrait painter active mid-16th century (Fig. 1). The painting belongs to the Fitzwilliam Museum, and came to the Institute for assessment before the exhibition: Degas: A Passion for Perfection (3 October 2017 – 14 January 2018).

Elisabeth de Valois (1545-1568) was the eldest daughter of Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici and married Philip II of Spain as his third wife when she turned 14. The original portrait was painted by Mor in 1565, when she was 20. Elisabeth died at 23, after miscarrying for the second time in 1568.

The Fitzwilliam portrait, although not by Anthonis Mor, is a faithful copy in a style extremely close to that of Mor. The original portrait has been copied many times by different artists with varying degrees of accuracy. The copies highlight her importance and maybe her popularity, and were likely made to be sent around Europe to the various Royal Courts. The copies of the original portrait (Fig. 2) show her in this exact costume, but the formats vary: portraits only, full length, half length… you name it! The Fitzwilliam version was acquired in 1909, along with a full length portrait of her husband on canvas.

Dendrochronology

Dendrochronology analysis was done to find out an approximate date of usage for the panel. Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is the dating technique that utilises the pattern of rings widths within a timber to determine the calendar period during which the tree grew. This is then matched to an existing database. The date of a tree-ring sequence must not be confused with the date of usage of a tree, as sapwood (which has the latest growth rings) is usually removed by panel markers. The analysis provides either a felling date range (when sapwood is present) or a terminus post-quem (when the sapwood is not present). Between the felling of the tree and the start of a painting, a fair amount of time can go by, as the wood travels and is often seasoned. The results of the analysis indicates a usage date for the wood after 1552 [1].

Condition of the painting

Although the portrait had a number of areas where the paint was flaking and vulnerable (Fig. 3), which were consolidated with sturgeon’s glue, it was in good overall condition.

The varnish that covered the surface had slightly yellowed, dulling the colours and flattening the fabulous dress full of jewellery worn by the sitter (Fig. 4).

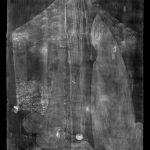

However, one thing really drew the eye: the lime green background . One could see the background looked dubious and was likely to have been overpainted (Fig. 5). Some fake cracks had also been painted in the background around the face, to try and integrate the area better, and the overall surface was cracked, reminding crocodile skin. It was decided with the curators to do some testing and find out if it was possible to remove the overpaint, what was underneath and what condition it was in.

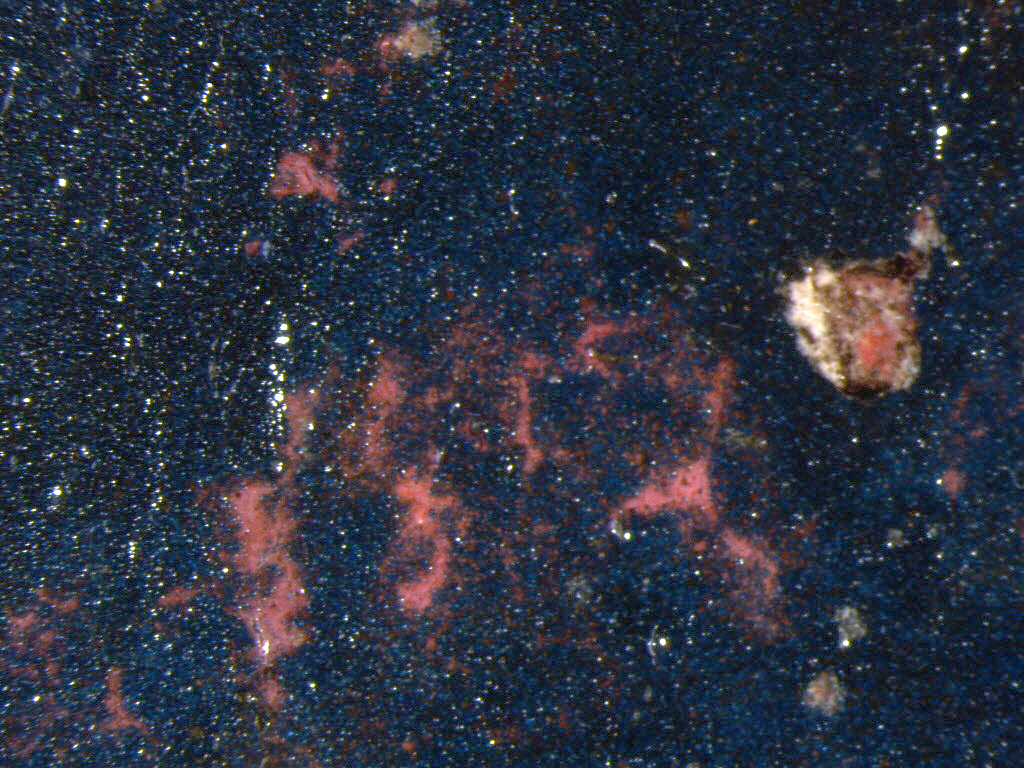

After close observation under the microscope, we came to the conclusion that most of the surface was covered by overpaint (Fig. 6).

Cross-section

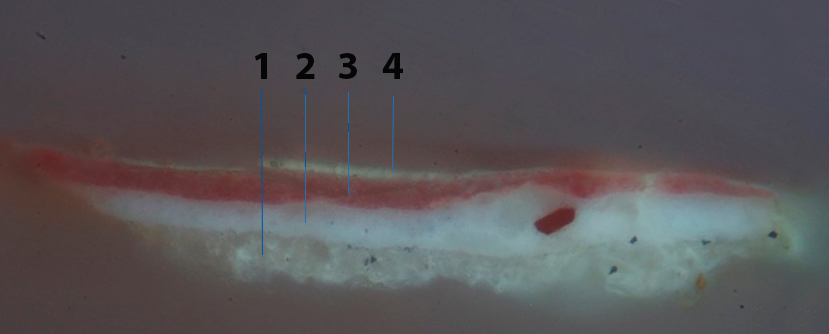

A paint sample was taken and set in resin (cross-section). The sample showed the original paint layer (2-3) was covered with two thick layers of overpaint (4-5) and non-original varnishes, tinted (6-7) and untinted (8-9) (Fig. 7).

Conservation Treatment

During testing, it was revealed that the overpaint could easily be removed. Three areas were tested; two showed an original paint layer underneath that appeared in good condition, and one test showed an abraded area. It is a difficult decision to remove such a large area of overpaint based on the three small test patches. But as the cleaning progressed (Fig. 8), it became clear that we were right to do this: the background was in good condition, apart from a small abraded area in the background close to the back of the head of the sitter. It seems astonishing that such a small damage warranted the overpainting of the whole background.

The original background is a dark green/brown, showing variations in opacity and in brush handling. It looks vibrant and lively, and complements the sitter’s red dress and pale rosy carnation.

After the removal, the painting was varnished (Fig. 9), the losses filled (Fig. 10) and retouched (Fig. 11) with reversible materials, and the abraded areas in the background were lightly dotted in. Treating this painting stabilised the materials (through the consolidation of flaking paint) and brought it a step closer to its original 16th-century style.

Camille Polkownik, 2nd year Post-Graduate Intern (2015-2017)

About the Author:

Ms Camille Polkownik graduated with a Master’s Degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Paintings in 2014, from the École nationale supérieure des arts visuels de La Cambre in Brussels (Belgium). She also has a Bachelor degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Painted Works (2011) from the Superior School of Fine Arts, in Avignon (France). She has interned at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Belgium), the Royal Museums of Fine Art of Brussels (Belgium), the Museum of Fine Arts in Nice (France), the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia) and in private studios.

Her current research projects include the study of extenders added to Prussian Blue; the quality variations in lead white and how they affect paint properties; and the characterisation of Prismatic Lead White, an unusual form of lead white, through X-ray Diffraction analysis and Polarised Light Microscopy.

To contact Camille: camille.polkownik@gmail.com

[1] Tyers, Ian, Dendrochronological Consultancy Report 907, pp. 1-4.

Titmus)

Titmus)