This oil on panel portrait belongs to the City of Lincoln and depicts the founder of the Charterhouse, London, Thomas Sutton (1532–1611). The painting has been lent to the Charterhouse since the 1970s and was recently sent to the Hamilton Kerr Institute for technical analysis and study, in the hope of clarifying long-standing questions about its origin.

THE PAINTING

The painting is attributed to an unknown English artist, but the date of the painting has been contested with two different theories as to the origin of the portrait. The date of c.1590 was suggested by Sir Roy Strong in the 1970s, and is based on the sitter’s age (Sutton would have been 58 in 1590) assuming that the portrait was painted from life. It was also postulated that the illustration of a cannon in the book, on which Sutton rests his hand, suggests that the sitter was at the time Master of the Ordnance (an office which Sutton held until 1594).

However, it has subsequently been suggested by the art historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, that the painting could have been a posthumous portrait of Sutton. Painting styles and portrait compositions do not change much between the late 16th century and early 17th century, making it difficult to judge on these aesthetic distinctions the date of a painting of this type. It was hoped that through technical examination, evidence of the painting’s making might come to light that could decide the long-standing question of whether this painting was a portrait from life or not.

During the examination of the painting, both under the microscope and using the other imaging techniques such as infra-red reflectography (IRR) and X-radiography, it became apparent that the painting has been severely damaged in its long history. These damages are old and hidden under several layers of restoration. It is common for paintings of this age to have suffered over time, but this painting is remarkable in the extent of the restorations currently present.

THE MAN BEHIND THE MYTH

Thomas Sutton was an enigmatic and shrewd Elizabethan financier who amassed a great fortune during his life and became something of a myth after his death. He was known to his contemporaries as ‘Croesus’ or ‘Riche Sutton’,[1] and had the reputation of being the richest commoner in England when he died in 1611 at the age of 79. Originating from Lincolnshire, Sutton was a talented civil servant and made money from wise investments and purchasing favourable leases. However, it was really through his somewhat disreputable practices as a money-lender that Sutton accumulated and expanded his fortune.[2] Usury, while legalised in 1570, was not considered wholly respectable and criticised as a way of extorting money.

Sutton bought the Charterhouse in 1611 for the grand sum of £13,000 but died later that year, leaving an astonishing sum of money (some £50,000) for the establishment of the hospital and school in his will. This was not popular with Sutton’s heir-at-law, his nephew Simon Baxter, who, displeased with his inheritance of £300, tried to storm the Charterhouse by force.[3] After his death, Sutton’s will was published, and the astonishing gesture of donating almost his entire fortune to a charitable cause transformed the careful and private businessman into a Protestant saint of charity, hailed by the clergy as a ‘hero’, a ‘saint’ and even ‘the right Phoenix of charity’.

This fame prompted an interest in his life, and since the career of Sutton as a reclusive ‘usurer’ was not palatable to his fans, more exciting tales of Sutton were spread. He was even portrayed as a valiant soldier/merchant prince, who, through his thirty agents abroad and his privateering exploits at sea, contributed to victory in the great patriotic wars against Spain. While these myths have been eroded over time, Sutton’s final gesture of charity in the founding of the Charterhouse has certainly given this sombre character a place in the history of London.

THE INSCRIPTIONS

The painting prominently displays two painted inscriptions and two coats of arms, all of which have been overpainted and are somewhat illegible in places. The two different coats of arms can be identified as Thomas Sutton’s personal coat of arms on the right-hand side, which was assigned to him after his death, and the Lincoln coat of arms on the left.

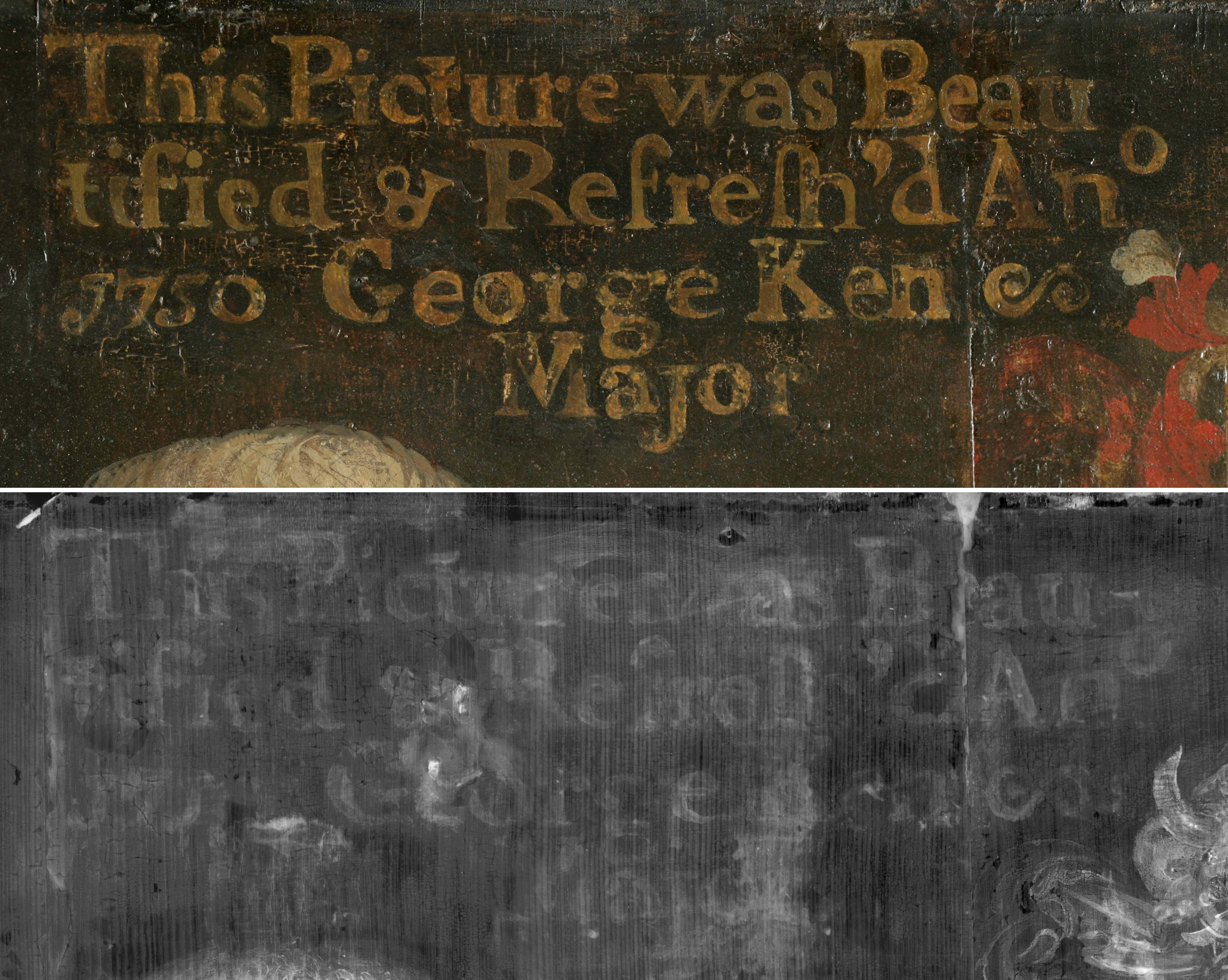

The inscription at the top, above Sutton’s head, is an unusual addition to a painting and refers to the restoration of the painting in the 18th century by the mayor of Lincoln. The inscription reads, “This Picture was Beau/tified & Refresh’d Ano/1750 George Ken/Major”.

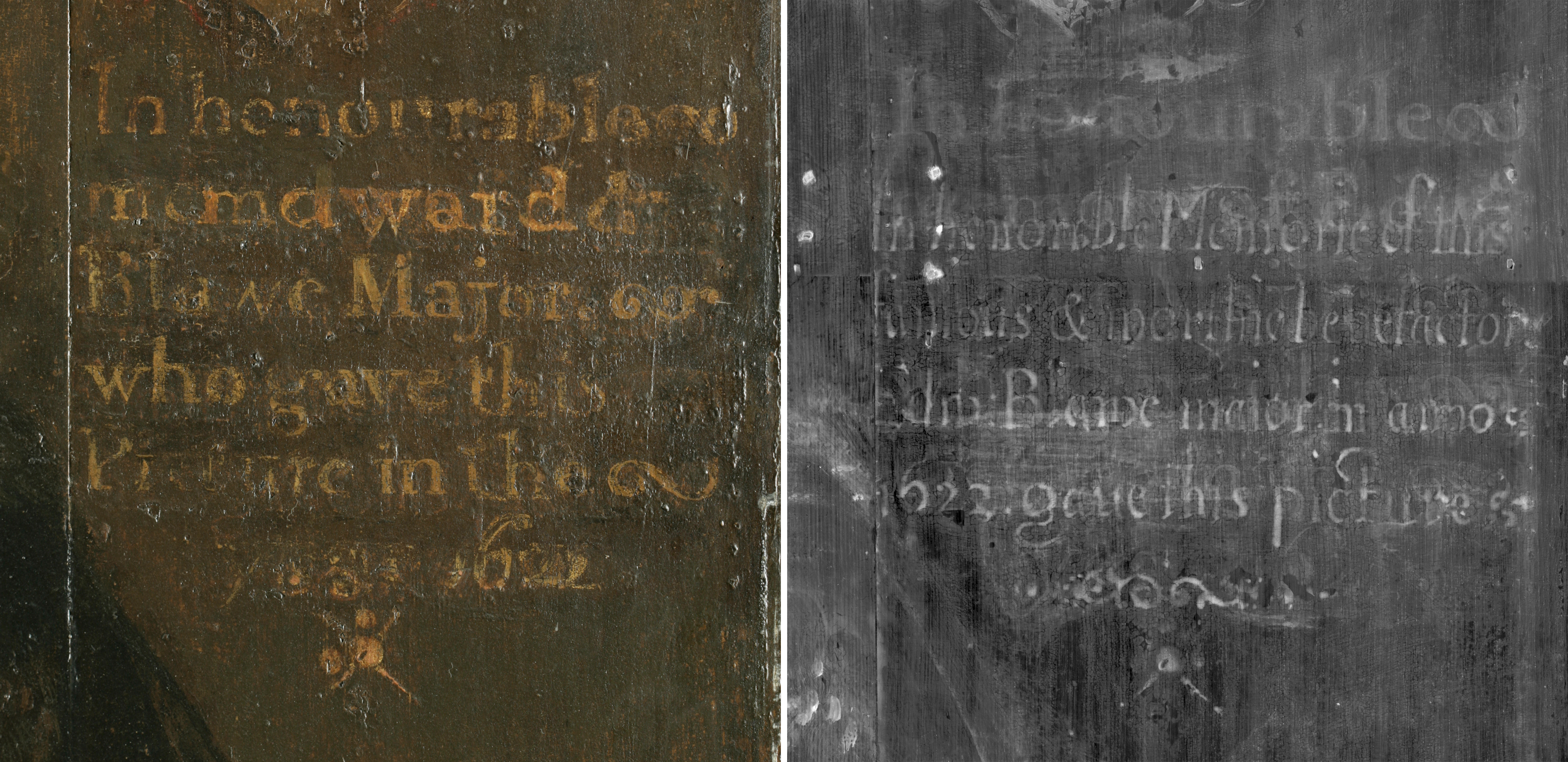

The other inscription is harder to read as it has been damaged and badly overpainted in the past. X-radiography is a technique by which we can see ‘through’ the paint layers, or more precisely, we see the density of the painting mapped out. In this case, the x-radiograph of the painting shows the original inscriptions underneath the overpaint (see figures. 2 and 3). In the x-radiograph, the older donation inscription is quite clear and reads, “In honorable Memorie of this/famous & mor— benefactor/Edm. Blawe major in anno/1622. gave this picture”.

This inscription refers to the mayor of Lincoln in 1621, Edward Blow, but what is less certain is whether the date refers to the paintings making or whether it was added as the date the painting was donated to the City of Lincoln.

THE PAINTING IN LINCOLN

These inscriptions give an insight into the function and history of this painting as a publically owned painting. The portrait is in fact mentioned in a Historical Account of Thomas Sutton written by the historian Philip Bearcroft in 1737. He writes: “The Lea∫e of the Par∫onage of Glentham was bequeathed to the Poor of the City of Lincoln out of Regard to his Father(…) And in Gratitude for this Benefaction, there is now in the Publick Hall of the City of Lincoln a whole length Picture of Mr. Sutton, with this in∫cription, Effigies Illu∫t: Thomӕ Sutton Armigeri, given according to the In∫cription, in 1622 by Edward Blawe E∫q; at that Time Mayor, and beatified and refre∫hed in 1710, at the Expence of the Corporation, whole Poor continue to be Fed to this Day out of the Par∫onage of Glentham.”

Despite the reference to the portrait being a full-length, when there is no physical evidence of the painting being cut down, much of what is written by Bearcroft fits in with what has been deciphered of the inscriptions from the technical analysis. The incongruity between the dates for the restoration became clear when looking at the inscription in the x-radiograph, as the year originally read 1710 but has been copied incorrectly to 1750 (see figure 6). This fits with the name of the mayor, as George Kent was the mayor in 1710, rather than Edward Fowler, the mayor in 1750.[4]

Bearcroft thinks that the portrait was given as a response to Sutton’s bequest of the lease of the Glentham parsonage – i.e. as a gift received after his death. This implies that the 1622 date of the portrait’s donation also corresponds to that of its making. In addition, from what we know of Sutton’s life, it seems unlikely that a personal portrait of the man (he only became a public figure after his death) would have ended up in Lincoln, as Sutton had little connection to the city at that period of his life.

DATING USING DENDROCHRONOLOGY

In addition to the historical evidence for the painting being a posthumous commission by the mayor of Lincoln in 1622, the dating of the panel using dendrochronology provides compelling evidence for this theory. Dendrochronology (or tree-ring dating) is a dating technique that uses the pattern of ring widths within a sample of timber to determine the calendar period within which the tree grew. The results for this painting gave the earliest felling date of c.1605 for the panel. If time is added onto this date for seasoning and processing of the wood, it becomes highly unlikely that this painting could have been made within Sutton’s lifetime.

This date certainly contradicts the idea that the open book is an indication that this portrait was made to commemorate a specific event in his career (e.g. his leaving office in 1594), or that is was painted while he was still the Master of Ordnance. It seems more likely if we consider this portrait to be a grateful representation of a man expressing the virtues of Christian charity, that it eludes to his more exciting and respectable methods of making his fortune.

SUMMARY

Technical analysis has been used in this study to clarify certain aspects of the painting and give weight and further evidence to historical theories about the painting. The clarification of the old inscriptions and the dating of the panel support has given credence to the theory that this painting was made in 1622, after Sutton’s death and rise to fame, and commissioned as a public painting by the mayor of Lincoln to celebrate a Lincolnshire worthy.

Sarah Bayliss, 2nd year Post-Graduate Intern

[1] Neal R. Shipley, “Thomas Sutton: Tudor-Stuart Moneylender,” Business History Review, Vol. L, No. 4 (Winter, 1976): 456-476.

[2] Stephen Porter, The London Charterhouse: A History of Thomas Sutton’s Charity (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2009), 9.

[3] Hugh Trevor-Roper, Thomas Sutton, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, accessed 14/10/2016, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26806?docPos=3

[4] It’s All About Lincoln, accessed 18/10/2016, http://www.itsaboutlincoln.co.uk/1701-to-1900.html

About the Author

Ms Sarah Bayliss is a graduate of the Post-graduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings at The Courtauld Institute in London. She also has a Master of Chemistry from the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK.

To contact Sarah Bayliss: sarahebayliss@gmail.com