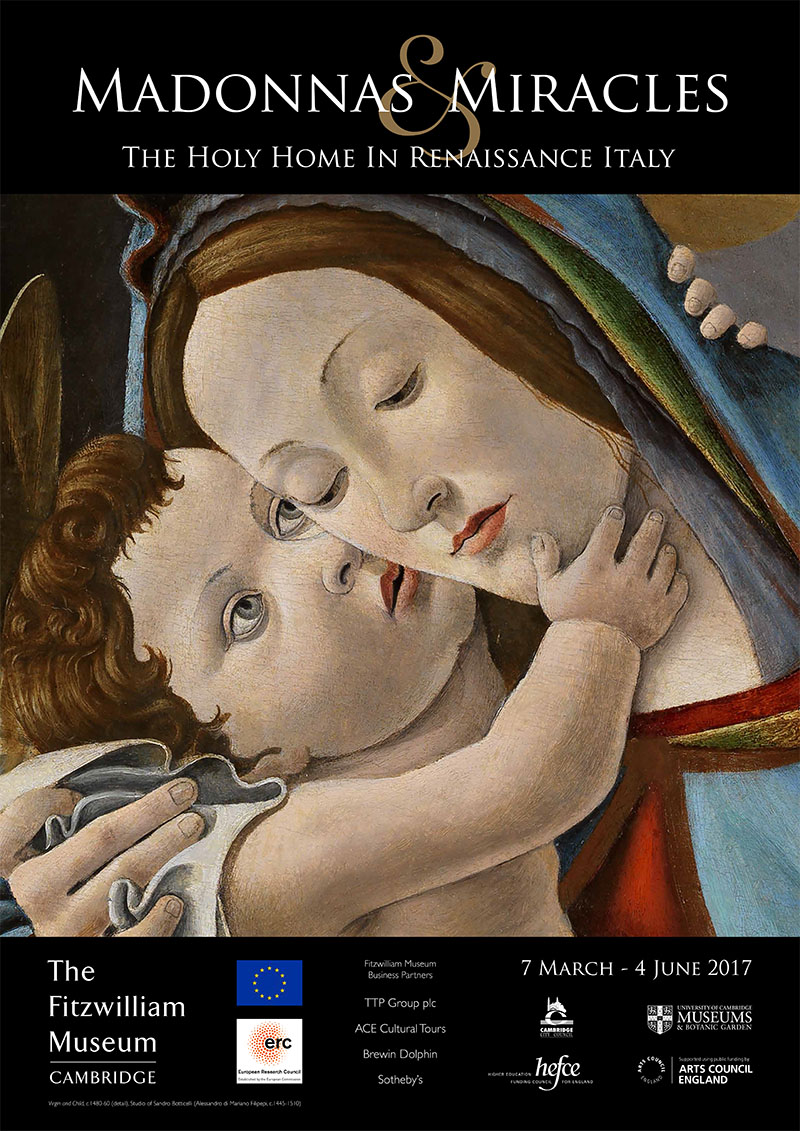

In preparation for the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition Madonnas and Miracles: Private Devotion in Renaissance Italy paintings from the Fitzwilliam Museum collection came to the Hamilton Kerr Institute to be restored, including this beautiful and colourful panel of the Madonna and Child by the Master of the Castello Nativity . When the painting arrived at the studio, the two main issues were a discoloured varnish layer and a very visible and irregular retouching covering the joint in the centre of the panel from top to bottom. This was my last project at the HKI; I left before I was able to finish it so Mary Kempski, Senior Paintings Conservator at the Institute, carried out the filling and retouching, bringing the treatment to completion.

Titmus)

Titmus)The artist

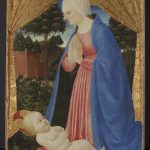

Little is known about The Master of the Castello Nativity. He was an Italian painter, active in Florence and Prato in the mid-15th century, as well as a follower and possible pupil or collaborator of Filippo Lippi (c. 1406-69). He was nicknamed after another of his paintings of the Virgin adoring the Christ Child which originally came from Castello and is now kept in Florence [1] Around 30 paintings have been ascribed to him, a few of them show the same composition, as can be seen in the versions in the Uffizi, Florence and in the Huntington Library, California. All three versions have similar features: the kneeling Virgin praying with the Child in front, the star on the Virgin’s shoulder (probably Stella Maris), the veils covering the head and the hands of the Virgin, the gold decoration of the robes, the vegetation and the golden rays around the baby. The three paintings are of a considerable size and the one from the Fitzwilliam is the smallest.

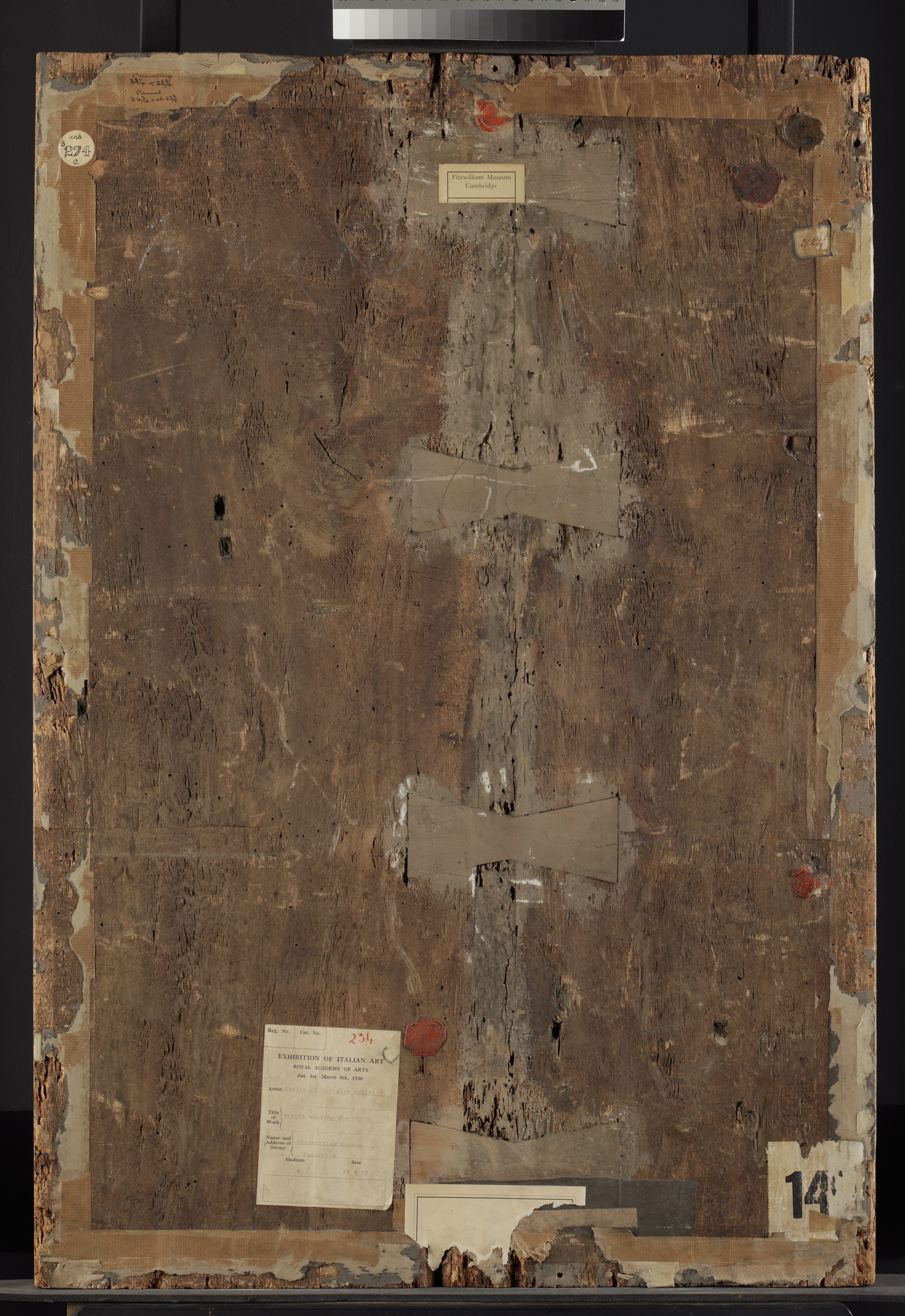

The panel

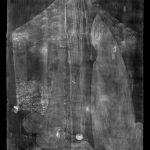

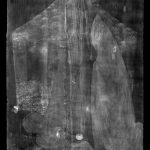

The wooden panel (86.7 cm x 59.4 cm x 3.4 cm), most likely poplar, consists of two boards with the grain running vertically. At the back, the surface is irregular and shows tool marks from the initial preparation of the panel. The woodworm damage in the central section is severe and may well have weakened the panel internally causing it to split, a damage now visible from the front. The visible open channels from the woodworm activity on the vertical edges of the panel indicate that the edges have been cut off and the general size reduced at some point. The presence of six rectangular holes on the back could be related to a previous use of the panel, although their function is currently unknown.

Titmus)

Titmus)The X-ray examination revealed the presence of an original piece of canvas covering the joint top to bottom and located under the ground and paint layers. It was common practice at this period to cover the defects and joints of the support with canvas soaked in glue before applying the ground layer. This would help level the surface and strengthen the weakest areas. Curiously, the canvas is missing just at the very bottom of the painting, but the reason for this is so far unknown.

Titmus)

Titmus)The painting technique

The paint was in good condition, apart from extensive retouching along the split, as well as in the bottom corners. Based on the appearance and handling of the paint, the figures are most likely painted with tempera, while the landscape appears to be done in oil. The detailed areas of vegetation display very thick impasto. Upon ageing, the oil layers have become more transparent, allowing the previous layers of oil underneath to be seen, as is the case in the roses and the trees.

The gold, probably water-gilded, has been re-gilded in some areas. To recreate the volume of the curtain of the pavilion, dark glazes have been applied to the gold drapery, and some engraved marks (scoring and punching) were applied to give the gold different textural reflections.

The treatment

The work started with a full optical examination. Ultraviolet light revealed a discoloured varnish layer (probably a natural resin as it fluoresces in UV light, although not strongly) and a discoloured and irregular retouching covering the joint.

González Juste)

González Juste)The painting was surface cleaned and the varnish removed. After removal of the top varnish layer, it was evident that there was still another varnish on the surface, in particular on the blue of the robe and the greens of the background. A stronger solution was used in order to remove the last remnants of the varnish. The removal of the varnish layer also involved the removal of the majority of the overpaint, although there were remnants on the joint of the boards in the bottom right corner, and some across the red robe. These remnants were tough and probably older than the rest, possibly in a different medium.

The removal of old fills from the central join revealed at least three campaigns of filling and retouching, covering areas of the original, which had caused bulkiness across the join. The removal of the fills recovered hidden areas of original paint, which were in good condition.

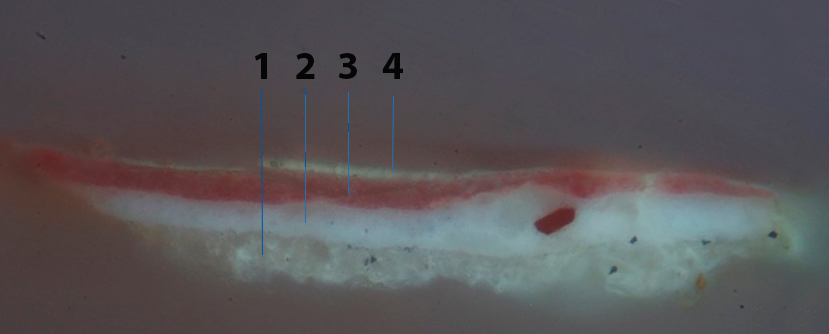

Due to the uneven and dull quality of the flesh tones and the blue and red robes after varnish removal, these areas were examined more closely and samples were taken to try and identify the nature of this top grey layer. The study of the cross-sections suggests that the grey layer mainly consisted of an aged natural resin, too oxidised to lift off with free solvents.

The sample shows that the remaining varnish layer extended into a crack in the underlying original glaze, confirming that it was not original. The cross-section displayed below is a sample from the red robe after initial varnish removal. It shows the ground layer, probably gypsum with some black particles (1), a white pinkish imprimatura with a big red particle (2), a red glaze (3), and the varnish layer (4).

González Juste)

González Juste)After several tests, it was decided that the painting could be greatly improved by removing this layer. As a result, this revealed brighter colours, such as the astonishing ultramarine blue robe and the delicacy of the veil covering the hands of the Virgin.

González Juste)

González Juste)

González Juste)

González Juste)The painting was brush-varnished and the losses were filled and retouched, and the area of damaged gilding in the halo was re-gilded.

Titmus)

Titmus)Carlos González Juste, 2nd year intern (2014-2016)

About the author

Carlos González Juste has a B.A. in History from the Complutense University in Madrid and a Degree in Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage from the Escuela Superior de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales in Madrid. He has been an intern in the Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid), other Spanish institutions and the Hamilton Kerr Institute, Cambridge. He has participated in some traditional pigment making projects (“Cuttings: Mindful Hands. Masterpieces of Illumination” by Factum Arte among other projects). He is currently completing his Masters degree in the Escuela Superior de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales in Madrid and working as a private conservator.

To contact Carlos González Juste: cgjuste@gmail.com