On April 27th 2016, Carlos Gonzalez Juste (2nd year post-grad intern), Mary Kempski (supervisor and senior conservator) and myself travelled to Deene Park, between Corby and Stamford (Northamptonshire), to take care of 12 paintings that have suffered from mould and record their profiles in order to monitor changes to their panel support curvatures.

Deene House is a sixteenth century property incorporating a medieval manor and has been occupied by the Brudenell family since 1514 up until this day. The house has a grand style, with many paintings of ancestors as well as family heirlooms. As this house is lived in and not a museum, no photos of its interior will be published, only details of the paintings and the work done on them.

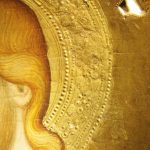

The twelve paintings are family portraits dating back from the seventeenth century. They are painted on oak panels by a British artist/studio and represent children and women at various ages. It is not known who they are but it seems likely they were members of the Brudenell family.

The paintings had suffered from humidity and had developed mould on the reverse of the panels. Not all panels were affected: some of them had been restored in 1966, and the reverse had been impregnated with a mixture of wax and resin, which acted as a barrier. The restored panels were thus protected from mould. However, this wax mixture also acted as moisture barrier, and these panels were less affected by the recent lowering of relative humidity in the house, which caused the more sensitive panels to warp and adopt a more pronounced curvature.

This in-situ had three objectives: remove the mould, take the curvature of the panels for monitoring and future comparison, and reframe the paintings to a conservation standard.

The paintings were first taken off the walls. All 12 could not be taken off at once since the space was restricted, which meant we could only work on 4 to 5 paintings at the same. As soon as one was done, it was put back on the wall and another one was brought in.

The mould was first removed using swabs and alcohol (click on photos to enlarge).

This enabled us to then unframe the paintings. A few of them had been restored by the Hamilton Kerr Institute several years before and already had proper framing. The rest were improperly framed, with nails holding the panels in their frames which were restricting their movements and could cause internal stresses. Luckily, no splits had developed or joints opened.

Once the paintings were out of their frames, the curvature profiles were taken on a piece of cardboard, and the current relative humidity and temperature of the room were written down. This will allow us to compare the curvatures at our next visit and understand the sensitivity of the wood to environmental conditions. Charlotte Brudenell (wife of the present owner of Deene Park) is very committed to giving the paintings the best possible conditions in their setting and is hoping to improve the climate control for the panels and all the paintings in the house.

The frames that had not been recently restored had their rebates lined with acid-free paper and cork spacers to accommodate the panels. Once the paintings were laid down in their frames, they were kept in place with brass strips at the middle of the top and bottom edges, so as to enable the panels to still move across the grain according to the relative humidity fluctuations. The paintings were then hung back on the wall.

This in-situ was a very good learning experience, as treating 12 paintings in a day was a great challenge, even with three people. It is interesting to see how one improves as the day wears on and how organisation evolves in order to be as economical as possible. Doing repetitive tasks, such as lining rebates and framing, greatly improves one’s skills and efficiency. The size of the artworks, as well as their location in the rooms and proximity to furniture, also required constant teamwork in order to move and re-hang them safely. The Hamilton Kerr Institute will soon return to Deene Park to continue the monitoring and preventive conservation of its artefacts.

Camille Polkownik – 1st year Post-Graduate Intern at the Hamilton Kerr Institute (2015-2017)

About the Author

Ms Camille Polkownik graduated with a Master Degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Paintings in 2014, from the École nationale supérieure des arts visuels de La Cambre in Brussels . She also has a Bachelor degree in the Conservation and Restoration of Painted Works (2011) from the Superior School of Fine Arts, in Avignon, France. She has interned in the Royal Institute for Culture Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Belgium), the Museum of Fine Arts in Nice (France), in private studios and at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia).

To contact Camille Polkownik: camille.polkownik@gmail.com