The Thornham Parva Retable was made circa 1330-1340, and is one of a very small number of such objects known to survive in Britain. It is a remarkable and important extant medieval English religious painting and sits behind the altar at the east end of the chancel in the tiny church of St Mary, Thornham Parva, Suffolk. In February 2019 a team of staff, students and interns from the Hamilton Kerr Institute drove to the church to conduct an inspection of the Retable, a duty performed annually since its extensive conservation treatment at the Institute almost 20 years ago.¹ While we were in the area we paid visits to two other churches, Yaxley and Eye, to see their rood screens; a genre of late medieval decorative painted church furniture with over 500 survivals in East Anglia.

The Thornham Parva Retable

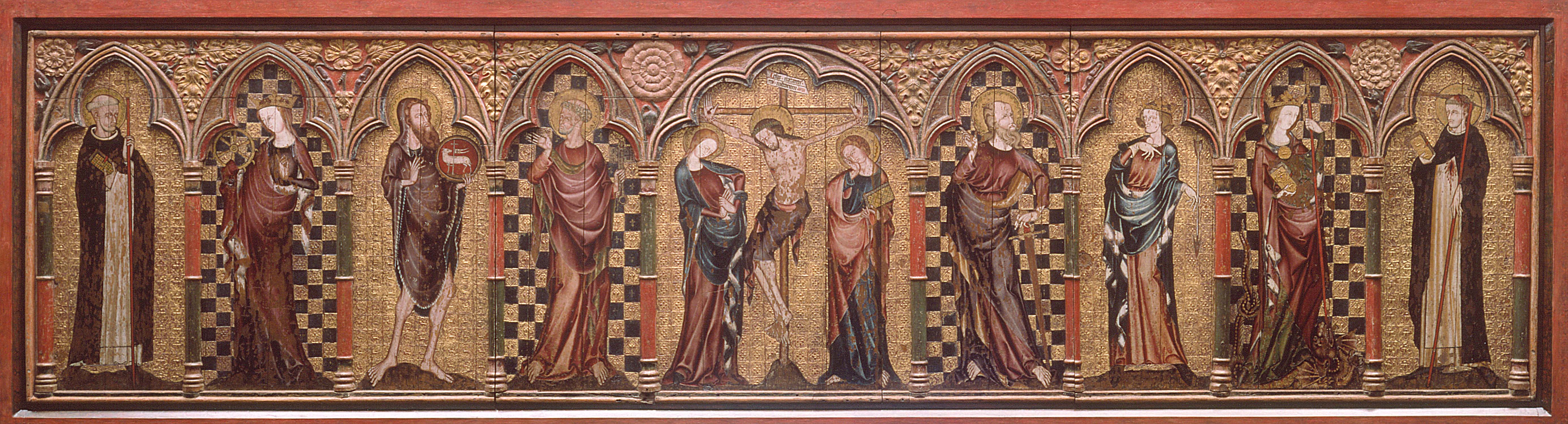

The Thornham Parva Retable is a horizontal panel some 3.9m long and 1.1m high, divided with columns into 9 sections which depict respectively, from left to right, Saints Dominic, Catherine, John the Baptist and Peter, the Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John the Evangelist, and Saints Paul, Edmund, Margaret and Peter Martyr. A Retable is an altarpiece; a panel decorated with devotional images that would have been positioned behind the altar and formed the backdrop to the liturgy. This Retable is thought to have been commissioned by the Dominican Priory at Thetford, Norfolk, and the depicted saints point to a Dominican patron. The Retable’s considerable size and quality are indicators of origins in a large and wealthy religious house. Stylistic similarities have been noted between the images on the Retable and designs on medieval glass fragments excavated from Thetford Priory ruins. The Cluny Frontal (Musée National du Moyen Age, Paris) has been identified as the companion piece, showing scenes from the life of the Virgin, which would have been positioned at the front of the altar table. The same craftsmen collaborated on both pieces.

The Retable is constructed from oak, and its straight grain indicates that it was imported from the Baltic, which is common in panel paintings in England from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern period. It also had a frame originally that would have been affixed to the support prior to painting and decoration. The original frame on the Cluny Frontal gives some indication of what its appearance might have been here. The panel is has a ground of chalk bound in animal glue, and analysis has suggested that the chalk may well have geological origins near Thetford. The design for the painting is drawn out onto the chalk layer, and some of this drawing was executed in the bright red pigment vermilion, which is unusual. Next, a layer of lead white in oil was applied. The sumptuous background decoration, comprising squares of gilded ‘tin-relief’ designs, would have been applied before the figures were painted. The name ‘tin-relief’ derives from the technique for this form of decoration. The reliefs are made of putty containing a mixture of pigments in resin and oil, which was pressed into a mould lined with tin-foil as a release layer. A variety of moulds were used here. This decorative technique is particularly interesting because it was to feature prominently in the later medieval rood screens of East Anglian churches. The figures are painted in a bright array of pigments including lead white, blue azurite, red and yellow earth pigments and copper-based greens. These were also mixed and blended to give other colours and tones. A greater range of colours and effects was created by glazing over the top with transparent pigments like red lake and the copper green pigment verdigris.

Rediscovered in 1927 in Thornham Hall, where it existed in three sections, the Retable was installed in St Mary’s and throughout the 20th century was transferred to several places in the country at various times, escaping war, travelling to an exhibition in France, and receiving intermittent conservation treatments to secure the paint and re-gild the background. It came to the HKI between 1996 and 2001, where, with funding support from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, English Heritage, World Monuments Fund and Samuel H Kress Foundation, it received full conservation, including consolidation (re-adhesion of flaking paint and ground), cleaning and removal of multiple and thick layers of overpaint, discoloured resin varnishes and previous wax-resin adhesives. Extensive research and technical analysis were carried out, including dendrochronology, X-ray and pigment analysis, and reconstructions to further explore certain aspects of the technique. As a result of the treatment, the majority of the paint represents the original medieval scheme and, despite the areas of damage and paint loss incurred from iconoclasm and neglect, the painting is in exceptional condition for its age. The conservation also involved monitoring and improvement of the environmental conditions within the church and provision of a protective enclosure for the Retable, and the work continues in the form of an annual inspection. These are all examples of what is known as preventive conservation.

Preventive conservation and the Thornham Parva Retable

Preventive conservation is a branch of conservation and preservation that involves creating and implementing policies to passively ensure the longevity of cultural heritage. The Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) has identified ten “Agents of Deterioration” that act as an outline for what might harm cultural heritage.² Therefore, preventive conservation is concerned with environmental monitoring, documentation, integrated pest management, proper handling policies, implementation of security measures, and protection from fire, water, pollution, and too much light. Some of the actions a conservator might take to mitigate the potential harm include periodic condition assessment of objects and their environment to keep a record of changes, and to be alert of any changes that might be a detriment to the preservation of a work so they may be mitigated. All of this work ensures the long-term protection of works of art, including pieces like the Thornham Parva Retable.

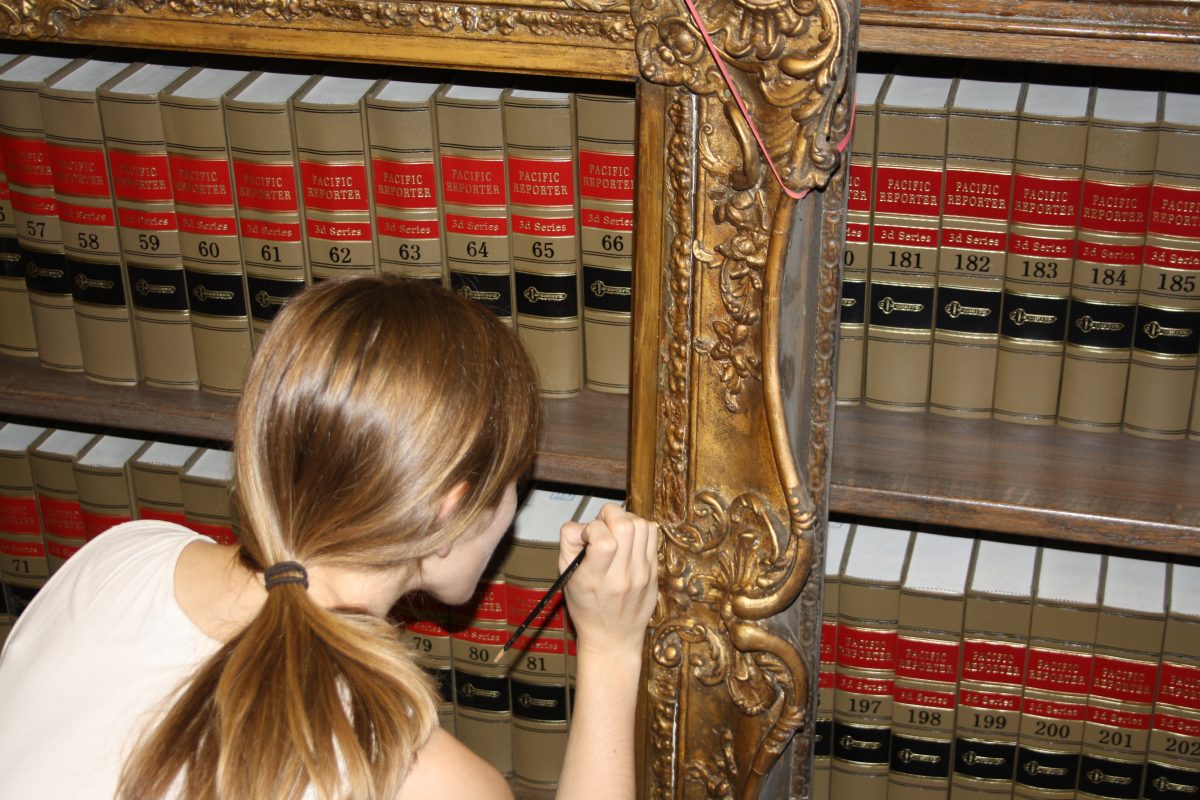

With this in mind, students and interns led by Dr Lucy Wrapson, all from the HKI, set out to Thornham Parva to do a yearly condition check of the Retable and lightly clean its surrounds. The Retable is set on the altar in a specially-made case, which protects the piece primarily from dust, changes in temperature and relative humidity, and possible theft or vandalism. The case was integrated into the structure of the nave so it was as unobtrusive as possible and still allowed the congregation to us it as it was intended. As part of our inspection, we were able to lower the glass in front of the Retable and get a close look using flashlights and head loupes. This way, we were able to look for any flaking or other damage that might have occurred over the course of the last year. Fortunately, there was no change in the paint and ground layers, except a bit of dust build up, which we very gently removed with a soft brush. Cobwebs around the case were also vacuumed up, as well as some salt efflorescence that perennially emerges between the floor and the wood panelling at the bottom of the case on the north side. While the source of this salt is not clear, it is important it is monitored and documented, as a change in the pattern can be an indication of something amiss with the building envelope. We also cleaned the inner and outer faces of the glass of dust and smears, so that the colours and details of the paintings can be fully appreciated.

The stable condition of the painted Retable speaks to what passive measures can do for the preservation of cultural heritage. For example, the red lake pigments are still very bright in the painting, which is very rare for an object of this age. These bright colours possibly suggest that the Retable was protected from bright light, which would have faded this fugitive pigment. Similarly, the wooden panels have been largely spared from damage by wood-boring insects, so they are still structurally sound. This special object was clearly valued by the community that had it made, and its stewards over many hundreds of years, including the current Thornham Parva community. The conservators at the HKI, in conjunction with the current church community, are able to use the principles of modern preventive conservation to continue to maintain the Retable for future generations.

Two Suffolk medieval rood screens

While we were in the area we had the opportunity to visit the rood screens in the churches of the nearby village of Yaxley, and the town of Eye. ‘Rood screen’ is the generic term that refers to the composite divisional structure that separated the chancel from the nave in a medieval church, and East Anglia contains the densest concentration of this type of object Europe-wide. Most screens that survive were constructed between the early 14th and mid-16th centuries, and they were known by the names rood loft, candlebeam, perke, and a host of other interchangeable terms. They were composite structures generally consisting of the dado (the lower part, bearing images of saints – this is usually the only part that survives in the church) and an upper traceried part, surmounted by a beam bearing the rood group (a wooden cross and figures of the Virgin and St John the Evangelist). The saints and angels depicted on screens acted as intercessors through whom the prayers of the local communities reached God. Screens were the work of multiple workshops that included carpenters, painters and sculptors, some of whom engaged in multiple crafts. They also would often have been fabricated piecemeal, with multiple donations, usually in the form of will bequests, for the construction or decoration of separate parts of the structure – for example, an individual or a local guild might dedicate a sum in their will towards the painting of their name saints. Many screens have been lost or severely defaced in bouts of iconoclasm following the Protestant Reformation and during the English Civil War. Of those that do survive, the work of certain craftsmen or workshops has been identified on a number of screens, which was a focus of Dr Lucy Wrapson’s PhD.³ Click here to view the blog post about the conservation of the rood screen in St Matthew’s church, Ipswich, in 2016.

St Mary’s church in Yaxley is a mainly 15th-century structure with a magnificent porch featuring flint flushwork, and a roof with carved angels and other figures. There is also a doom painting above the chancel arch. There is beautiful gilded tin relief to be seen on this screen, including a charming little face with a sticking-out tongue, and the saints’ garments are decorated with intricate brocade patterns. We looked closely at the carving and carpentry, which features intricate designs and is the output of the same group of craftsmen who worked on the screen at nearby Eye.

As Eye was a wealthy wool town in medieval times, the church here was notably large and grand. In this screen, the dado is medieval and most of the rood loft and beam with rood group is the early 20th-century work of Ninian Comper. The painted saints on this screen are very different in style to those on the Yaxley screen, being much more generic and less refined (but still charming). Here the saints were generally arranged male-female alternately, whereas those on the Yaxley screen were mostly female. The tin relief designs in the background here are much simpler than at Eye. Lucy highlighted the similarities of the carving and tracery designs on the spandrels and in the lower dado with the Yaxley screen and pointed to the remains of a dedicatory inscription on the loft.

Preventive conservation measures are important for the protection of rood screens, although sadly many exist in churches with uncontrollable humidity, temperature and light levels and are deteriorating as a result and suffer damage from insects such as deathwatch beetle. The visits we made today were an insight into the treasures that survive hidden in East Anglia’s churches, and the story of the Thornham Parva Retable exemplifies what is possible with the enthusiasm, support and collaboration of people with diverse interests, knowledge and professional skills, and what might be achieved for rood screens in the future.

Katharine Waldron and Ellen Nigro, 1st year Post-Graduate Interns (2018-2020)

NOTES

1. Massing, A., ed., The Thornham Parva Retable. Technique, Conservation and Context of an English Medieval Painting (Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge and Harvey Miller Publishers, 2003).

2. Canadian Conservation Institute, ‘Agents of Deterioration’. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/agents-deterioration.html, February 2019.

3. Wrapson, L., ‘Patterns of Production: a technical art historical study of East Anglia’s late medieval screens’ (PhD this, University of Cambridge, 2013).

About the Authors:

Ellen Nigro graduated from the University of Delaware in 2013 with a B.A. in Art Conservation and Art History. After gaining internship experience through projects at the Freer and Sackler Galleries, Shelburne Museum, Villanova University, and the Chrysler Museum, she entered the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC). Her projects in the program included developing a consolidation strategy for a matte, underbound, 19th-century Thai panel painting, and completing a technical study on it. She earned her M.S. from WUDPAC in 2018 after her third-year internship at the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis as the Fulbright-American Friends of the Mauritshuis Intern.

To contact Ellen: emn37@cam.ac.uk

After completing a BA in History of Art at the University of Warwick, Katharine graduated from The Courtauld Institute of Art in 2018 with a Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings. One of her projects involved the conservation and technical research of a modified 17th-century harpsichord lid, which led to her third-year dissertation project on historical copper green glazes. She has worked for Katherine Ara Ltd. and as an intern with the National Trust, the House of Lords, the National Maritime Museum, the V&A, and the RCE in the Netherlands as a Zibby Garnett scholar. Among her current projects at the HKI, Katharine is involved with research into the pigments and techniques of church polychromy in East Anglia.

To contact Katharine: kjw74@cam.ac.uk