The BAPCR (British Association of Paintings Conservator-Restorers) conference on nineteenth-century painting practice and conservation took place at the Wallace Collection on the 7th of October, 2016.

The keynote speaker for the first session was Sally Woodcock (Hamilton Kerr Institute), who is currently undertaking doctoral research on the Charles Roberson archive and the supply of painting materials in Britain between 1820 and 1920. The archive is currently housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute. The findings shared by Ms Woodcock opened our eyes to the less familiar materials that nineteenth-century painters ordered and used. In some cases, these materials could easily be misinterpreted as later restoration campaigns, such as panel backed stretchers and double-lined canvases. In addition, it was also interesting to see documented evidence of the extent of the restoration services provided in Britain during this period, exemplified by procedures such as the enlargement of artworks during painting, which was surprisingly a regular request for colourmen at the time.

Jacob Simon (National Portrait Gallery) shared his recent research on the increased employment of conservators by the growing public collections in the nineteenth-century. Mr Simon provided case studies of major galleries in London at the time, which helped demonstrate the growing recognition of paintings conservators in the museum sector. The expanding interest and importance of environmental conditions in relation to the care of artworks was mentioned by Mr Simon and was later discussed in depth by Nicola Costaras.

Nicola Costaras (Victoria and Albert Museum) addressed a number of nineteenth-century documentary sources, which provide insight to the early views of museum curators and conservators regarding the environmental conditions at the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). During the nineteenth-century, the Head of Collections was observing and monitoring drying crack patterns in paintings in order to determine whether heat and light contributed to their development. The talk gave us an understanding of the various views and concerns that existed in relation to the premature formation of drying cracks in paintings. Furthermore, we were able form an appreciation of nineteenth-century conservators’ curiosity and desire to understand this phenomenon, as well as the most efficient ways to prevent it.

Dr. Leslie Carlyle (author of The Artist’s Assistant and Associate Professor at the New University of Lisbon) shed light on the importance of her new research, which could lead to changes in the ways we observe paintings. Dr. Carlyle presented the main findings of a thirty-year long research project, which were published as a part of the MOLART Fellowship project (1999), which draws upon evidence found in historical documents, painting case studies and historically accurate reconstructions.

Nineteenth-century paintings are notorious for the difficulties they present during varnish removal. Lidwien Speleers (Dordrecht Museum) shared her experience in treating a painting by Jacob Maris which displayed solvent sensitivity. Drawing upon documentary evidence and empirical testing, Ms Speleers was able to predict the solvent sensitive passages within the painting and achieve successful treatment.

Artists’ reworkings represent another difficulty when it comes to the treatment and interpretation of nineteenth-century paintings. Rosalind Whitehouse (private conservator) shared a series of observations she made during the treatment of a nineteenth-century equestrian group portrait. The painting showed complicated layer structure consisting of dirt layers between painting campaigns, indicating that the painting had been worked on over a long period of time. Roxane Sperber (Yale Center for British Art) discussed the treatment of a painting by the British artist John Linnell, with particular focus on the artist’s practice of ‘retouching’ his own paintings. Ms Sperber found documentary evidence recording Linnell’s practice of reworking his paintings in order to please his patrons. Such reworkings have previously been interpreted as restoration campaigns, signifying the importance of understanding the methods of artists when undertaking conservation treatments. Michaela Straub (Hamilton Kerr Institute) also shared her research and experience of treating two paintings by the Royal Academy artist Alfred East. Ms Straub was able to detect areas that had been reworked by the artist through a thorough technical study. The research was also aided by literary references in the form of a treatise written by East himself, as well as the artist’s account in the Roberson Archive.

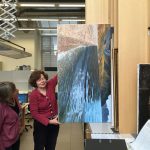

The volume of artists’ writings and contemporary documentary sources referred to throughout the conference served as a reminder of the Victorian painters’ desire to document their observations and thoughts on painting processes. For example, Adele Wright (Tate) gave us a close look at the writings of Eugène Delacroix and his immediate contemporaries in order to understand the innovative thoughts that lead to his specific painting technique. During her time as a student at the Hamilton Kerr Institute Ms Wright produced a reconstruction of Delacroix’s The Lion and the Snake, which provided insight into the artist’s technique and also helped inform the treatment of the painting.

The remaining speakers presented technical studies, which showed the varying painting techniques of the time. Nienke Woltman and Suzanne Veldink (Rijksmuseum) presented a technical survey of thirteen paintings by the nineteenth-century Dutch painter George Hendrick Breitner. The paintings form part of Breitner’s famous ‘kimono’ series, which was exhibited for the first time at the Rijksmuseum in 2016 (Breitner: Girl in a Kimono, Feb 20-May 22 2016). Fabio Frezzato (CSG Palladio s.r.l., Vicenza) and his colleagues presented the technical findings of a study involving forty-eight artworks by the Italian painter Giovanni Boldini, who was active in London and Paris during the mid-nineteenth century. In addition, Nele Bordt and Katy Sanders-Blessley (Royal Collection Trust) carried out research on the unique collection of portraits by the Austrian painter Rudolf Swoboda. Another talk focused on the research conducted by Gabriella Macaro et al. (The National Gallery), which involved revisiting existing technical research on paintings by the Barbizon School artists at the National Gallery, London. Ms Macaro’s research built upon previous findings by Ashok Roy, whilst also taking advantage of the more advanced analytical equipment now available at the National Gallery. Her talk was completed by Mrs Hayley Tomlinson, who spoke about the manuals on the practice of painting written by Ernest Victor Hareux, artists and teacher in the late 19th century. Since he was close to the artists of the Barbizon school, he had prime information on their practice and painting techniques.

The speakers highlighted the need for finding patterns by collating more information on nineteenth-century paintings. Methods of how conservators could share information, and the importance of funding for research projects were also discussed .

It is very exciting to think of the years to come, as more nineteenth-century paintings will be coming into our conservation studios for treatment, providing a great opportunity for in-depth research. The postprints of this conference are expected to be published during the summer of 2017 and will contain the papers that the researchers presented.

Jae Youn Chung – 1st year Post Graduate Intern at the Hamilton Kerr Institute

Ms Jae Youn Chung recently graduated with a Postgraduate Diploma in Conservation of Easel Paintings at The Courtauld Institute of Art. She moved to London in 2013 after graduating from Ewha Womans University (Seoul, South Korea) the same year, with combined degrees of BFA in Paintings and Ceramic Arts, BA in Art History and Professional English.

To contact Jae Youn Chung: paintingconservator.jyc@gmail.com