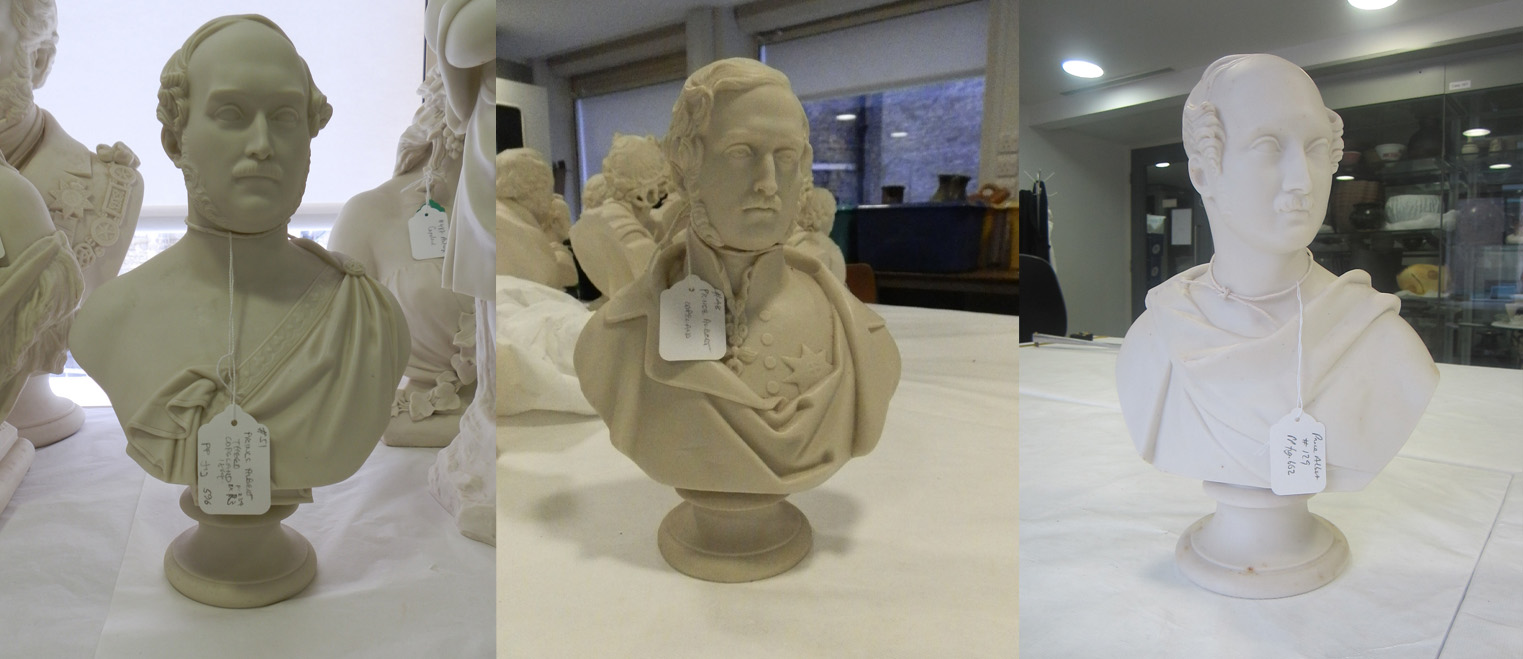

In the past year, the Applied Arts team has faced a monumental task: processing a group of 360 newly acquired pieces of Parian-ware (or Parian) porcelain, predominantly busts, in preparation for an upcoming exhibition. Most were dirty and many were separated from their original bases, which had become jumbled up. The scale of the project required that we think differently about how to care for the objects, finding an efficient way of processing them while respecting individual conservation needs.

The Glynn Collection of Parian-ware was acquired by the Fitzwilliam Museum in 2016 as part of the Acceptance in Lieu of Inheritance Tax scheme. Largely featuring busts of Classical characters and Victorian public figures, it provides an important insight into lives deemed worthy of commemoration in 19th-century England.

Acquiring such a significant collection opened up exciting possibilities for interpretation and display. The exhibition Flux (opens March 2018 in the Octagon gallery) is guest-curated by the artist and historian Matt Smith. As well as producing his own art, predominantly in clay, Matt has extensive experience of curating museum collections, often re-interpreting them from the view of an outsider. Flux will make use of his own unconventional Parian-ware (most fascinatingly produced in black Parian!) highlighting the Fitzwilliam’s historic collection and making it more relevant to a contemporary audience. The Flux display will accompany a major exhibition of studio pottery, Things of Beauty Growing, which will showcase ceramics sourced by the Yale Center for British Art, in New Haven, USA.

Parian-ware is named after the Greek Island Paros, known for its white statuary marble that was popular in the Classical world, which the porcelain imitates in appearance. Parian was a development of the biscuit (or bisque) porcelain used primarily by factories in France, such as Sèvres, to produce small-scale statue-like figures. This was developed further by porcelain manufacturers in Staffordshire, Britain, in the mid-19th century in order to give the surface a more reflective, marble-like finish. The slip-casting method, where liquid porcelain is poured into a detailed mould, allowed mass-production; making affordable, marble-like statues and busts available to middle-class Victorian homes. Parian was popularised by many British factories, right through to its decline in the early twentieth century. It was produced by many famous names such as Coalport, Wedgwood and Copeland. Factories competed with one another to obtain the finest Parian ‘recipe’. This has resulted in the many pieces within our collection having very different finishes, textures and weights. They vary greatly in density, porosity and colour: there are many shades of white and a few are tinted with coloured slips. Several busts are mounted on separate Parian bases, attached with threaded metal dowels. All these aspects need to be taken into account when treating each object.

The considerable size of the Glynn Parian-ware Collection made it necessary to develop a methodology that would allow streamlining the process of accessioning and conserving the porcelain in preparation for the Flux exhibition. The collection has occupied most of the available work surfaces in the department for much of the year, and clearing space was a priority. The first step required the combined effort of Departmental Technician Timothy Matthews and Research Assistant Helen Ritchie, who examined, photographed, measured and described the objects one by one, recording all information on a spreadsheet and eventually assigning each a museum accession number.

The condition was assessed by Penny Bendall, an independent ceramics conservator, who identified which objects required more complex conservation treatments, such as the reattachment of broken parts, removal of old repairs and re-mounting on bases. The vast majority just needed cleaning in order for them to be appreciated properly and to be made suitable for public display. The porcelain had more than likely been stored in different conditions and cared for in different ways by different owners. While many of the larger busts appeared to have been kept outside, their surface weathered and discoloured by accumulated dirt, smaller statues were far cleaner. Timothy Matthews and Assistant Conservator Flavia Ravaioli removed surface deposits using an enzyme-based detergent that activates in warm water. You will see from the photographs that a small amount of detergent was initially applied by brush and left on the objects’ surface for a few minutes to allow the enzymes to work. The detergent was then worked over the surface with the brush, taking care not to scratch the surface, until all the dirt had lifted. This was followed by thorough rinsing with specially-filtered water to remove all residues of the detergent. Finally, the porcelain was dried with soft cloths, then left in a warm place until completely dry.

When cleaning Parian-ware, we are very mindful of areas of restoration, the porosity of the surface, the presence of metal elements and old labels. When encountering a restored piece of Parian, we do nothing more than dust it with a dry brush, as using detergent and water could weaken or remove previous joins or restorations. A small handful of restored pieces were cleaned with acetone on small cotton wool swabs to allow more localised application.

Once clean, the objects were labelled with their accession number, photographed, and stored away to await display in the spring. So far 260 pieces have been completed. Only 100 more to go!

Timothy Matthews, Departmental Technician

Flavia Ravaioli, Assistant Conservator