There are 374 prints by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) in the Fitzwilliam Museum, many of which are fine and rich impressions, and a further 251 sheets attributed to followers of Dürer. I have recently enjoyed the opportunity to look closely at some of these prints as part of an ongoing project to conserve and remount them.

The prints come from a number of sources, including a core group of 127 engravings owned by Lord Fitzwilliam. These were bound together in an album (22.I.3) by Henry Woodburn in 1811, with Lord Fitzwilliam’s inscription on the fly-leaf title sheet, ‘Oeuvres / d’Albert Durer’. In 1876 the prints from this album, along with etchings, engravings and woodcuts from five others including Rembrandt and Martin Schöngauer, were sent to the British Museum for conservation and re-mounting. The sheets were mounted individually in ‘sunk mounts’ of a standard Royal size (559mm 406mm), with gilded edges, and stamped with the lettering ‘Albrecht Dürer’ and a number corresponding to catalogue raisonnés of Dürer’s prints (Ottley and Bartsch) (Fig. 1). This type of mount was devised by the Department of Prints & Drawings at the British Museum around the middle of the 19th century in an effort to limit unnecessary handling of the sheets and reduce abrasion to the surface of works of art on paper that were previously stored loose in portfolios. A bevelled opening was cut in a piece of cardboard slightly larger than the print, a second ‘backboard’ was pasted to it and the print mounted in the aperture. The surface of the print sits below the surrounding board thus protecting it from wear.

‘Today, the availability of paper board is taken for granted, but until the beginning of the 19th century it had been neither a widely used nor a readily procurable commodity […] In the British Museum, pure quality, stiff rag cream-coloured board from J M Whatman had been utilized from the 1840s. The high quality of this board is certainly a major factor in the fine condition of the Museum’s collections today.’1

The opportunity to look very closely at these prints has revealed other work that appears to have been undertaken at the British Museum during remounting. It was common practice to adhere the prints to a thin machine-made paper; this lining supported torn or weak areas of the print and made it easier to attach the print to the mount without causing distortion. I have discovered examples where small losses to the original engravings have been very skilfully recreated, hand-drawn in ink on the lining paper (Fig. 2).

It is not uncommon for intaglio prints such as etchings and engravings, especially those by Old Masters, to be trimmed to the plate-mark (the indentation around the image created by the metal plate being pressed into the dampened paper as it moves through the press). There is often a printed ink line along this indentation created either by the artist as a drawn border to the image, or a result of ink residue not wiped from the extreme edge of the plate. Trimming of the sheets was often surprisingly haphazard with the very edge of the printed image sometimes being removed in the process. As a result, prints with a complete margin, even when very narrow, are highly prized. The recent study of the Fitzwilliam’s Dürers has revealed some instances where missing sections of platemarks have been re-touched in ink, either on the primary support or the lining paper. We can be fairly confident that this was carried out when the objects were re-mounted as there is an example where the line has slipped slightly onto the mount (Fig. 3).

There are also examples of prints that have a curious pink line at the plate-mark (Fig. 4). It is thought that these marks were made with a copying pencil.2 When dry, the marks of a copying pencil resemble graphite, but they contain an aniline dye that is soluble in water and permanently changes colour if it becomes wet. While purple/violet is most common, a range of colours has been noted.3 It is possible that the colour-change occurred due to moisture from the mounting adhesive.

Not all the prints are in good condition. For example, when viewed in transmitted light it becomes apparent that the impression of St Thomas (AD.5.22-201) is only a fragment of the original sheet and very thin in places (Fig. 5). It would have certainly sustained more damage without the support of the lining paper carefully applied at the British Museum.

There are fascinating inscriptions on some mounts where scholars have noted the merits or flaws of various impressions. Describing an impression of the engraving Virgin and child with the pear (P.3092-R), given to the Museum by Arthur W. Young in 1934, Thomas Barlow writes, ‘It seems to me an unusually brilliant impression with this mark (anchor in a circle watermark). It is more like a Bull’s Head impression. Your existing impression is excellent and a more pleasing impression, this is rather over inked on the right side. But a very interesting impression. I should be very chary of disposing of it.’4 Campbell Dodgson added his agreement below: ‘It is very fine, shows platemark more completely, and ought to be kept.’5

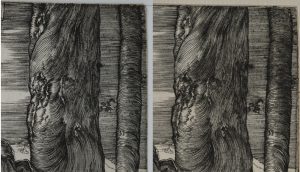

Subtle differences between impressions can be noted within the collection. The ink is a little blurred in places on the impression of the Virgin and Child with the Pear on the right, where the plate was less thoroughly wiped (Fig. 6). The dramatic loss of richness and detail, the result of a worn printing plate, becomes apparent when comparing two impressions of St. George on Foot (Fig. 7).

The mounts are now nearly 150 years old and, while the materials used were the best available at the time, they are showing their age. There are handling marks which would be distracting if the works were displayed, and the mounts are also generally much thinner than those we would use today. The linings make the prints look unnaturally flat and prevent access to the back of the sheets, which can often provide valuable information to researchers. A number of pale brown/orange spots have also developed over time. They occur on both the prints and mounts which suggests they are a result of either impurity in the board or in the adhesive used to attach the prints (Fig. 8).

Inevitably with a collection of this size, the documentation and conservation project will take some time to complete and I hope to update this blog with further observations as the work continues. The approach to treatment is dictated by the condition of each print, but in many cases they are being lifted from the old mounts once all the original inscriptions have been recorded.

Where possible, the linings are being removed (Fig. 9) and the adhesive used to attach them is reduced or removed. This process has already revealed some interesting inscriptions and collector’s stamps. The papers used to make these prints are beautiful and very good quality: they have responded well to washing treatments and the spotty discolouration has reduced to a point where it is no longer distracting (Fig.10).

Tears and losses are repaired and the original British Museum retouched fills are being retained in-situ where appropriate. Once the prints have been lightly pressed they are inlaid into a slightly larger sheet of paper, a technique that allows access to the back of the sheet, and remounted in 100% cotton Museum-board mounts.

I am hopeful that this work will continue to protect these beautiful prints for another 150 years.