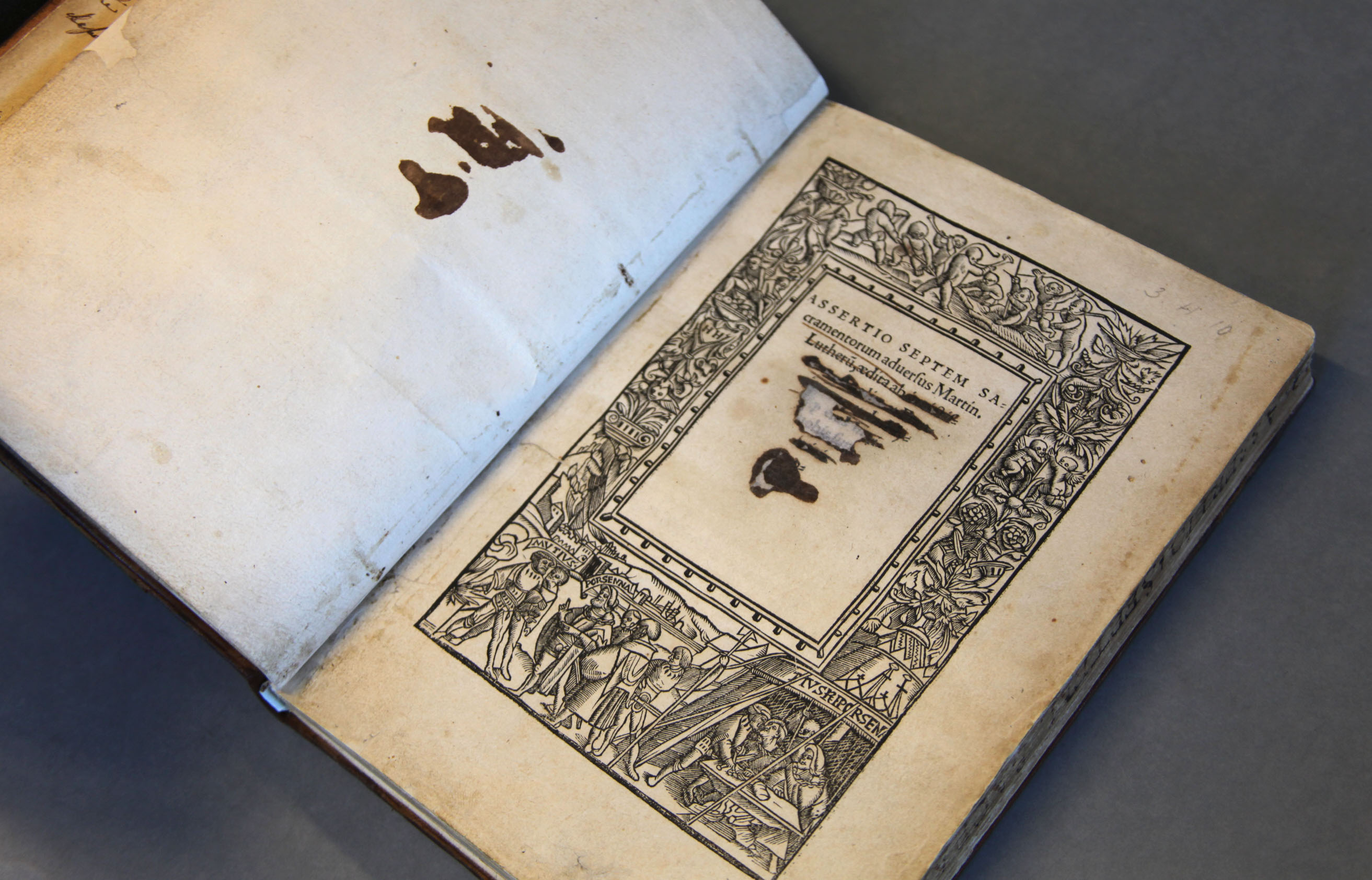

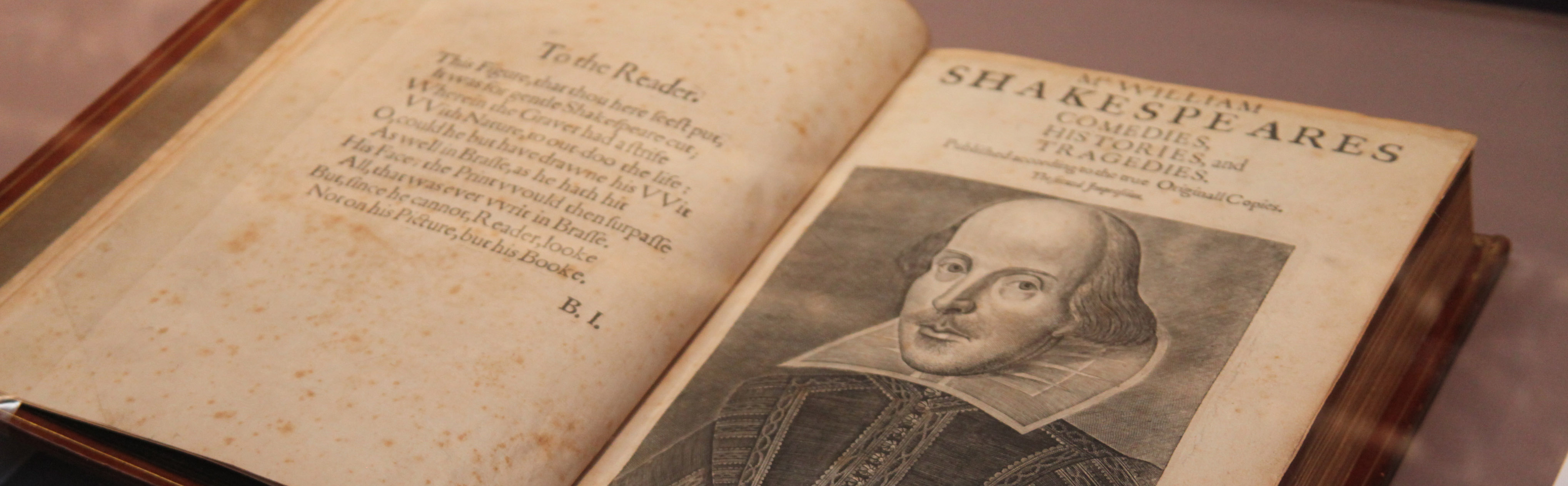

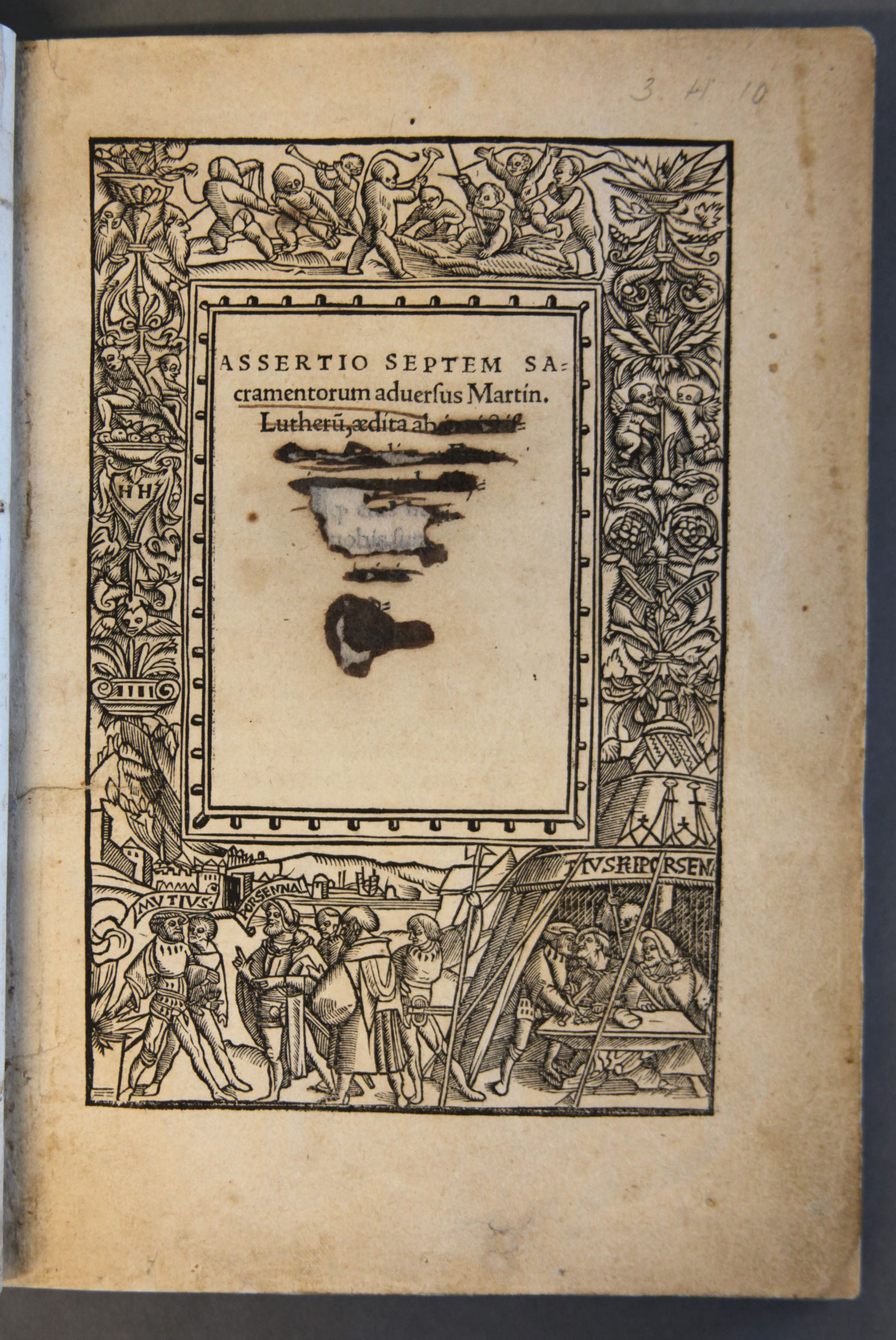

Henry VIII of England continues to attract attention. This time it is not about one of his many wives but about a book he wrote, the very book which granted him the title of Defender of the Faith, a title still assigned to British Sovereigns today. Henry VIII was a highly educated man and in the years before he turned against the Pope and the Church of Rome, he wrote a treatise called The Defence of the Seven Sacraments against Luther. The book is a theological treatise, dedicated to Pope Leo X, defending the Catholic Church against Martin Luther’s attack on Indulgences, and was printed in London in 1521.

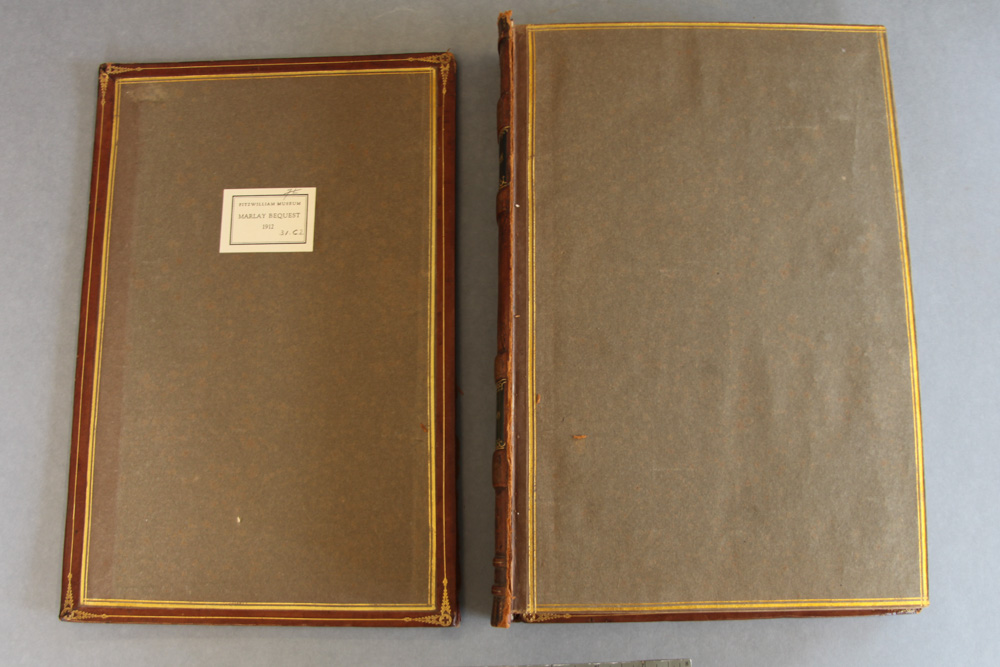

The Fitzwilliam Museum’s copy

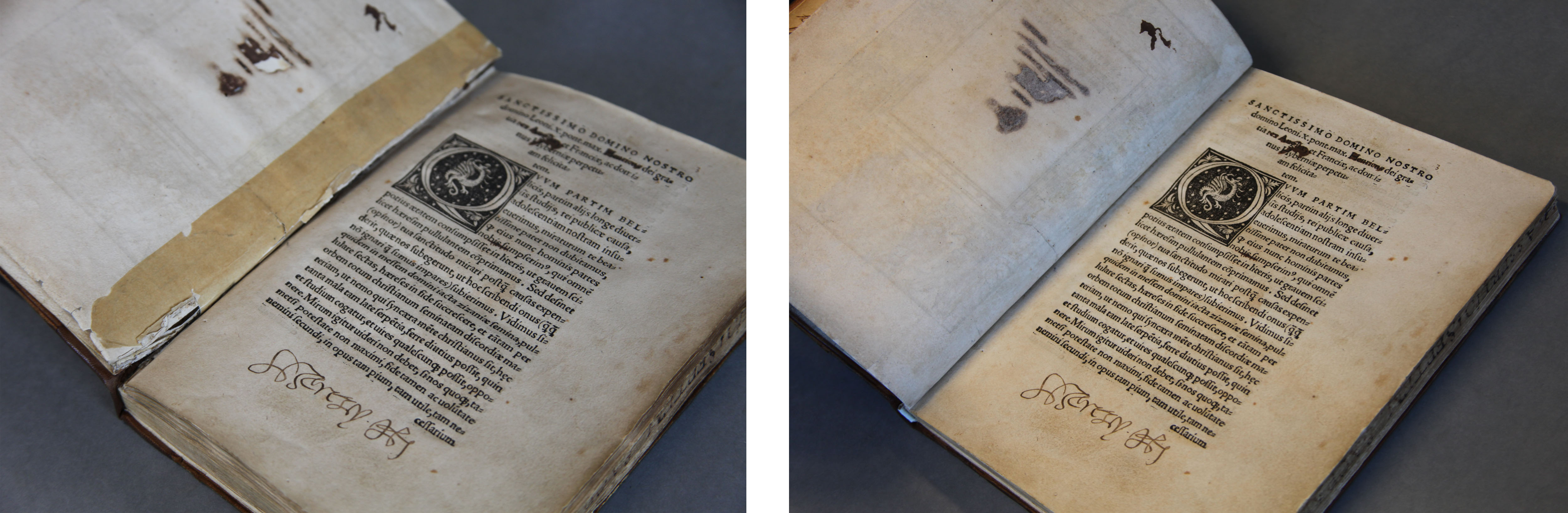

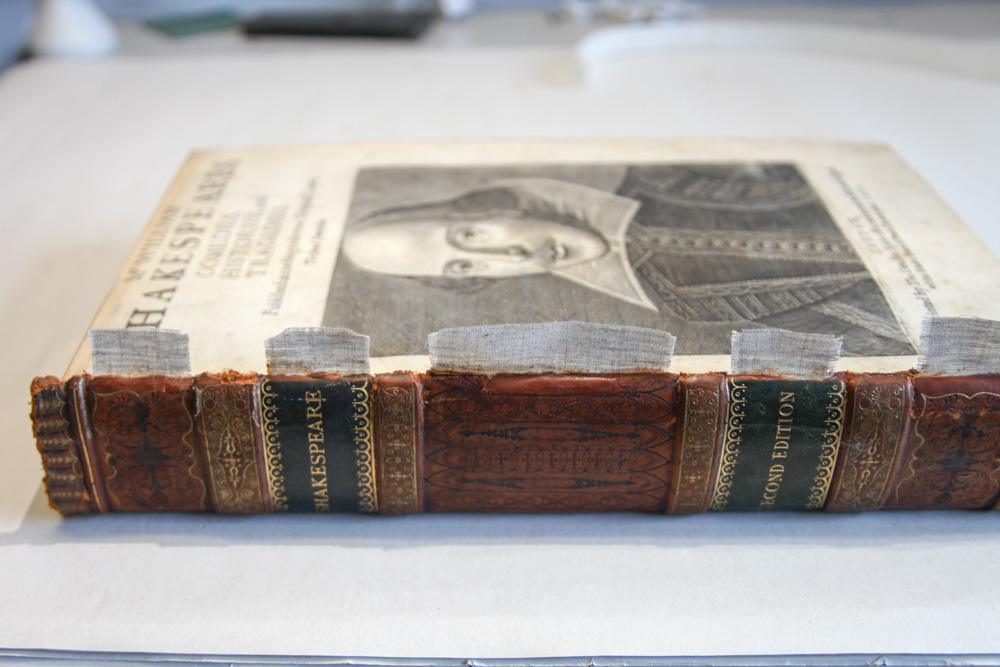

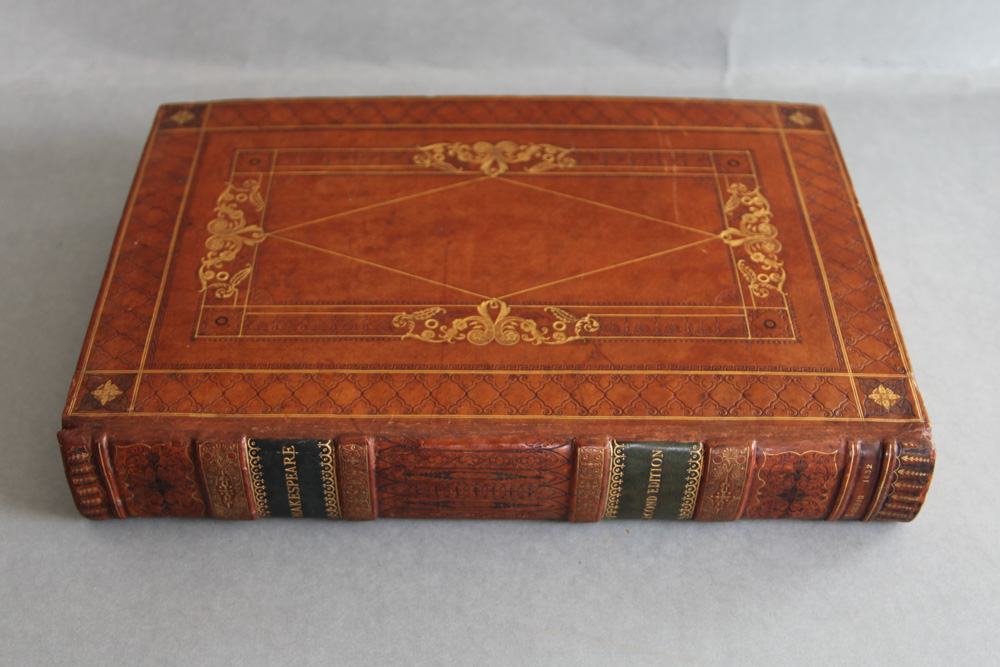

The Fitzwilliam Museum’s copy of the book is one of 27 copies that were sent to Rome by Henry to be distributed among the Cardinals of the Church after approbation by the Pope1. As we are currently working towards an exhibition on Money, Image, and Power in Tudor and Stuart England (spring 2019), the book was brought up to the conservation studio, and this is when the exciting detective work started. In fact, the book has a number of interesting physical features which I tried to unravel, helped by my curatorial and conservation colleagues Suzanne Reynolds and Edward Cheese, in order to choose the most appropriate conservation treatment and extract as much information as possible about its history.

The authentic features

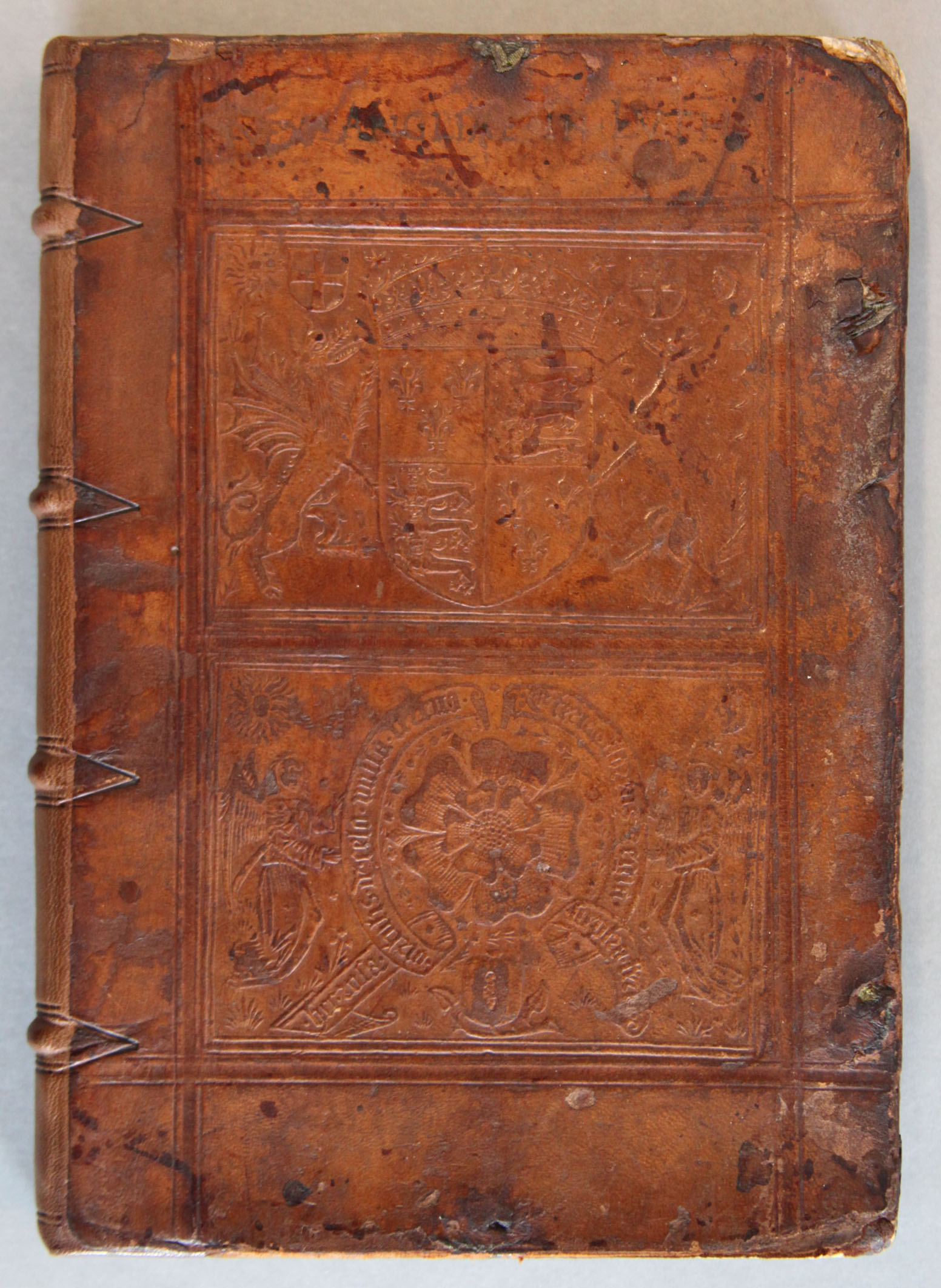

I was able to validate several authentic features of our copy, the large signature of Henry VIII at the beginning and end of the text being the most obvious evidence. The sixteenth-century full leather binding is blind-stamped with the Royal arms and the Tudor rose in a double panel. These stamps are attributed to the London binder John Reynes2 and prove the authenticity of the binding. The title page is decorated with an elaborate woodcut border designed by Hans Holbein (1497-1543) which has been recorded by Gordon as part of the original features of the first edition of the treatise3.

Other features

Other features bear witness of the life of this copy and tell us about its owners, its condition and its uses.

Signs on the binding

The front board shows an inscription that has been scratched in the leather. We can read REX ANGLIAE IN LVTH meaning “The King of England against Luther”. The foredge has been inscribed with the title, along with an intriguing sign. This symbol is hard to identify and we came up with two suggestions of what it could be: a cross-bearing orb or a pomegranate. Please get in touch if you have seen this sign used on other books – there are possible links to Queen Catherine of Aragon.

Inside the book

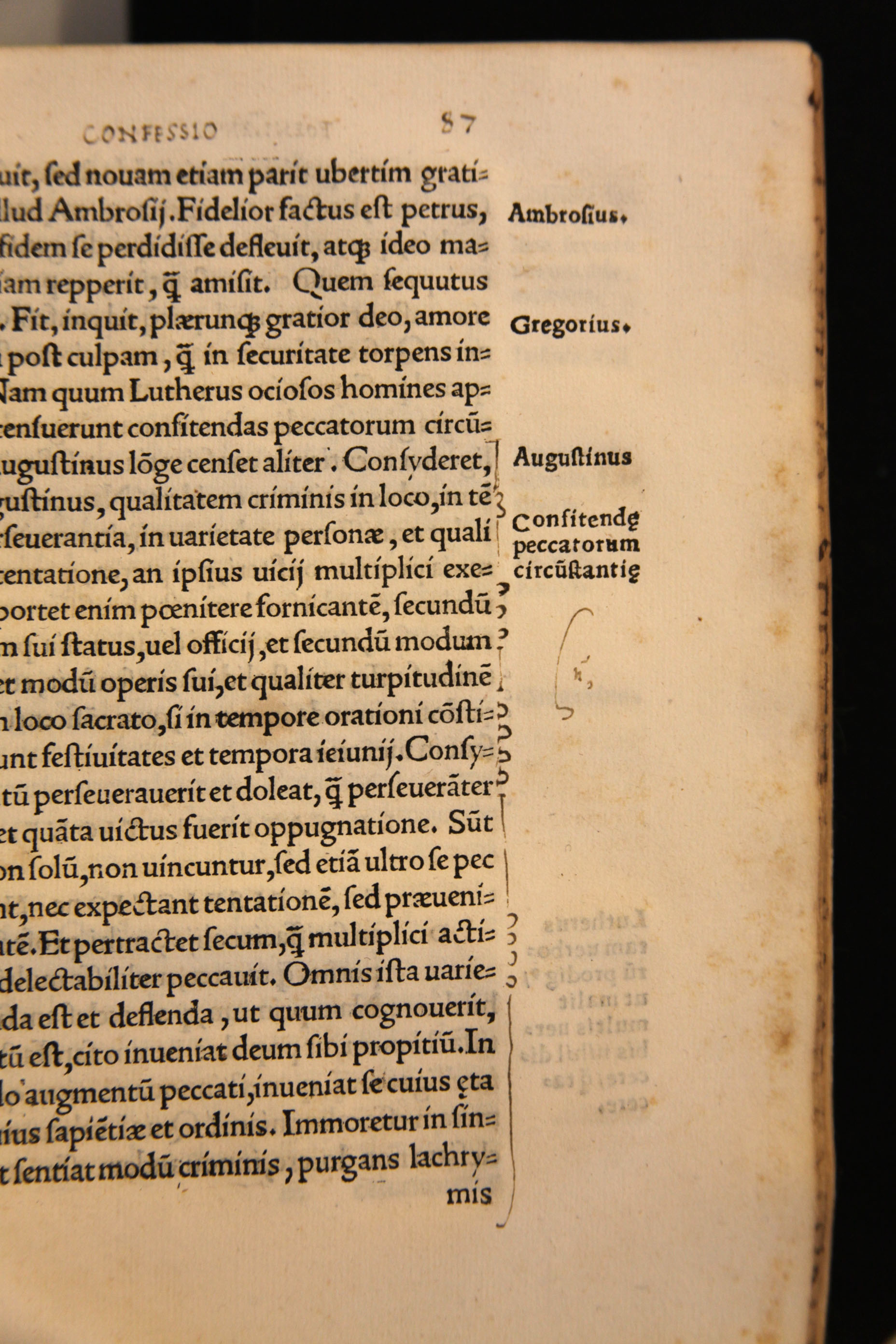

The pages have been numbered by hand, and the running titles have also been added by hand by a reader comfortable with the Latin of the text, using an elegant humanistic script. This reader also annotated the text extensively.

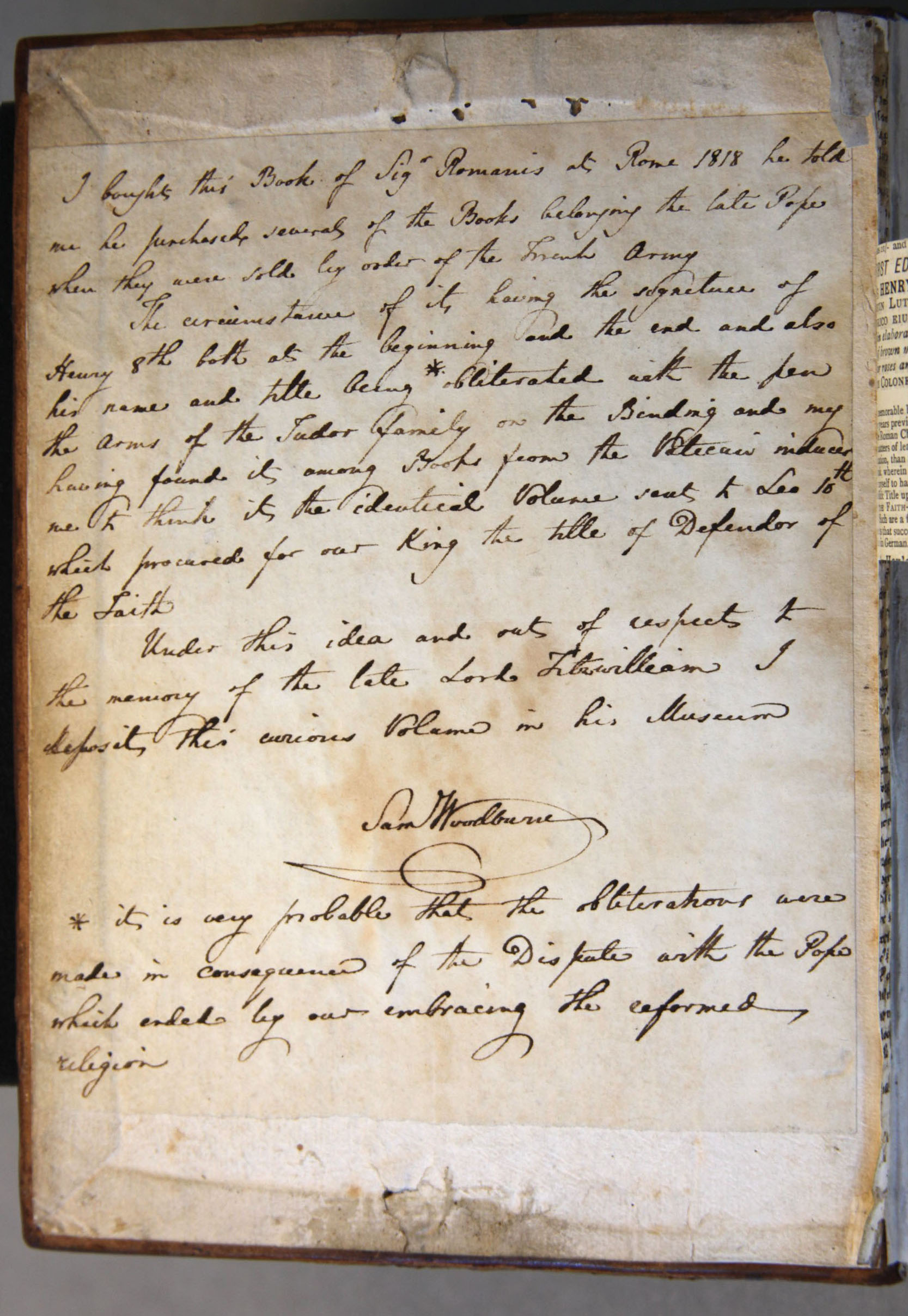

The front pastedown

A nineteenth-century manuscript note on paper is adhered to the front pastedown. It is signed by Samuel Woodburn (1780/5-1853, art dealer and expert on Old Master Drawings) who explains that he bought the book from Signor Romanis at Rome in 1818. Napoleon’s invasion of Rome (1798) had a powerful impact on the Vatican Library as well as its manuscripts. Book dealers coming from England and other countries followed the army and acquired many books and illuminated cuttings. If Samuel Woodburn’s note is true, the book was purchased by Signor Romanis when several of the books belonging to the late Pope were sold by order of the French Army.

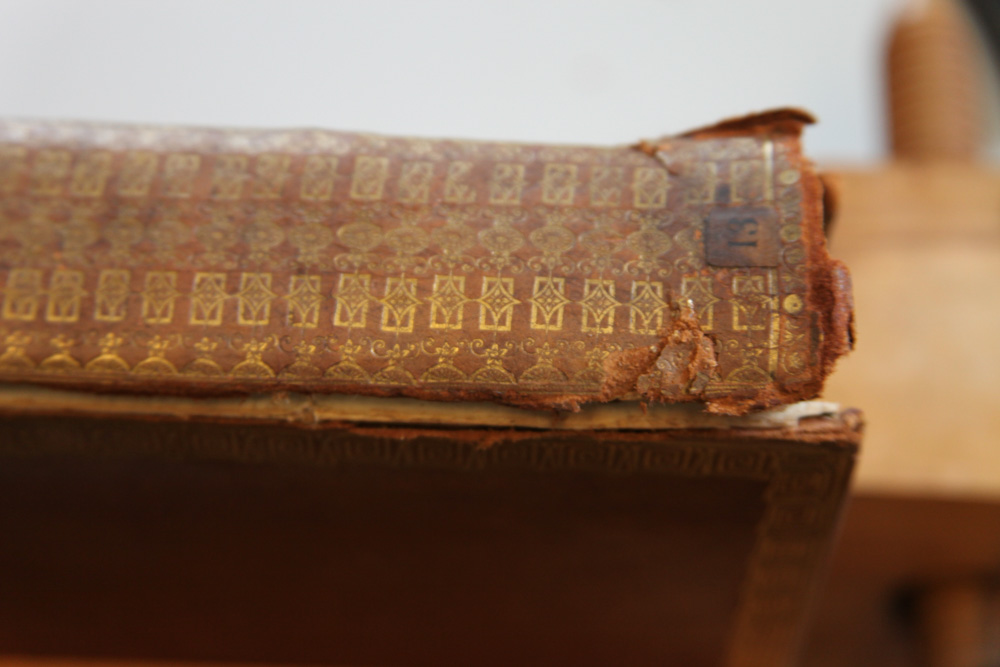

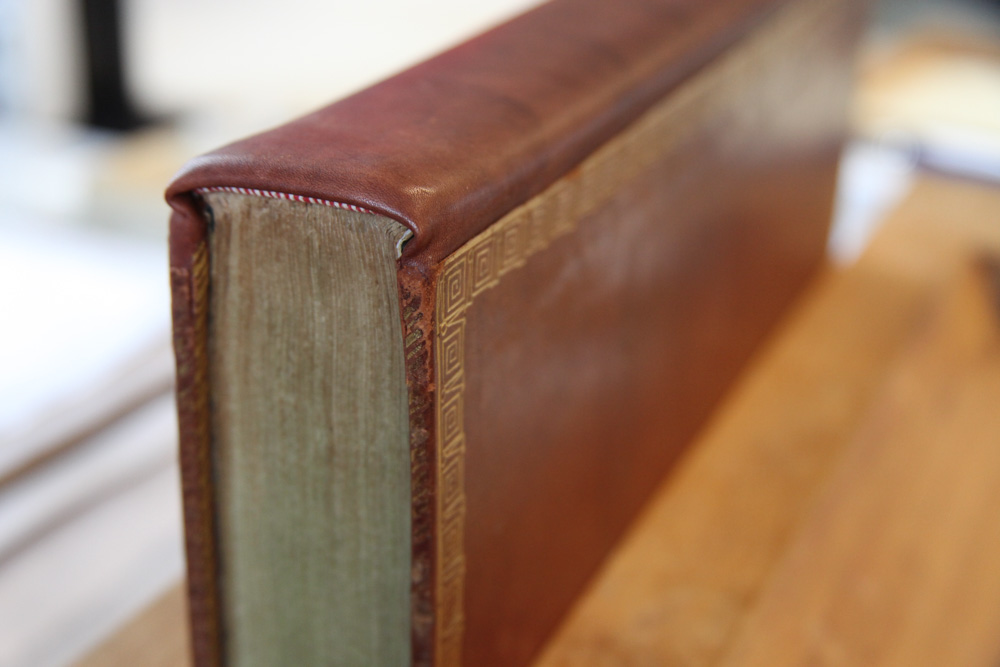

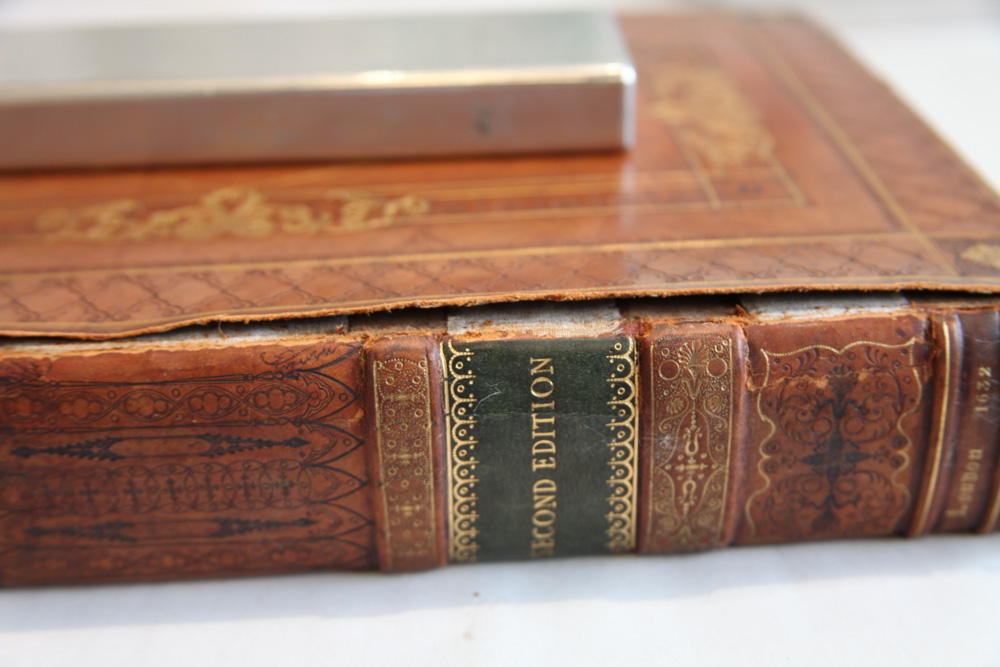

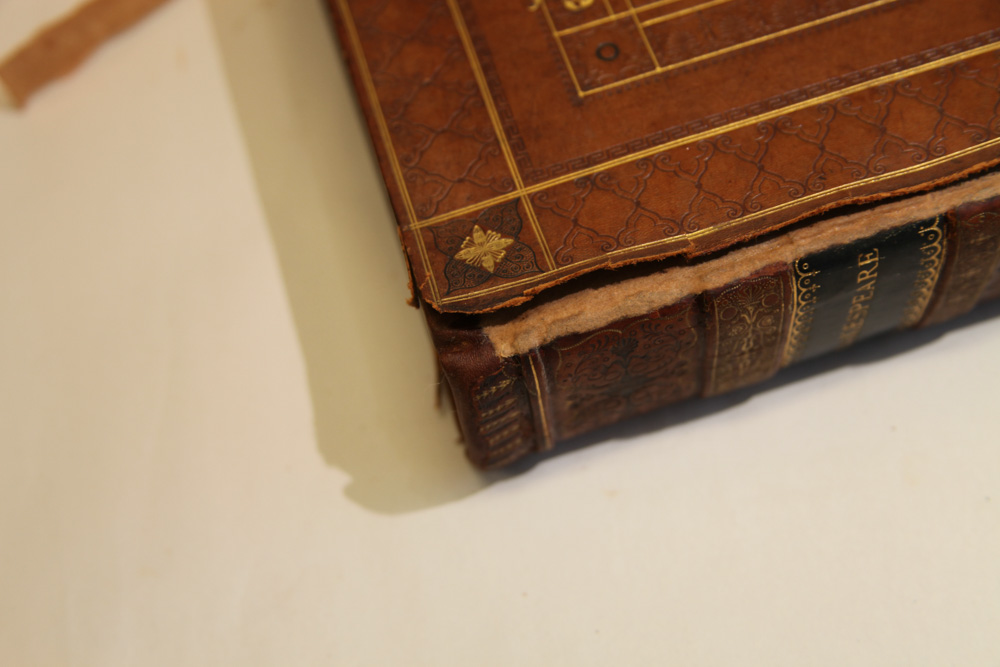

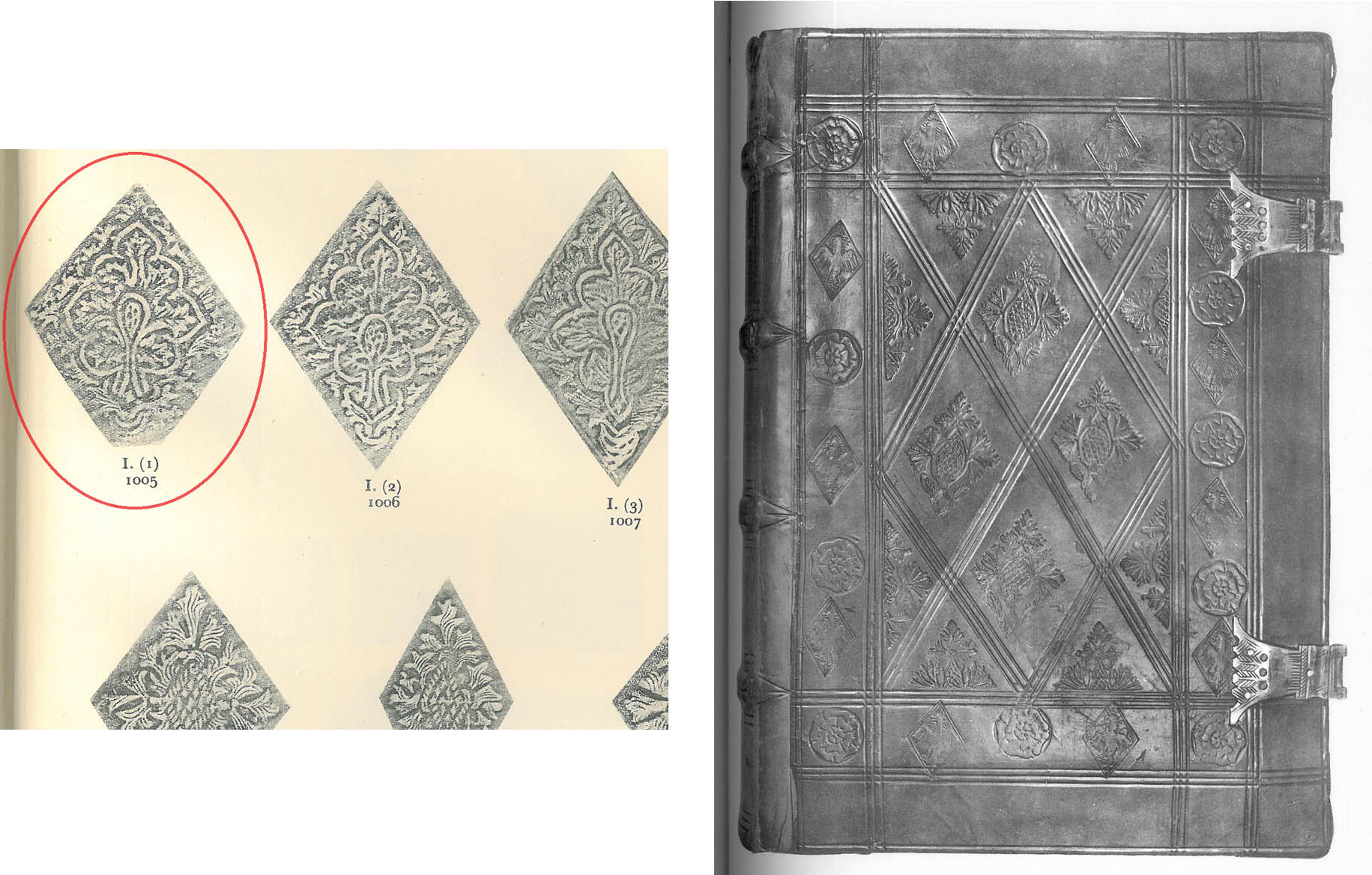

Remains of a former reback

One final feature. When removing the existing leather spine repair, blind-tooled brown leather remains were found underneath the original leather along the joints, suggesting a former reback. The patterns that are still visible indicate that the leather came from a fairly large late fifteenth – or early sixteenth-century binding with a central panel of triple-lined lozenges framed by foliate ornaments. The stamp used for these ornaments and the style of the layout is very similar to one recorded by Basil Oldham in English Blind-Stamped Bindings4, confirming the date of the re-used leather.

Conservation treatment

Let’s get on with some conservation treatment now!

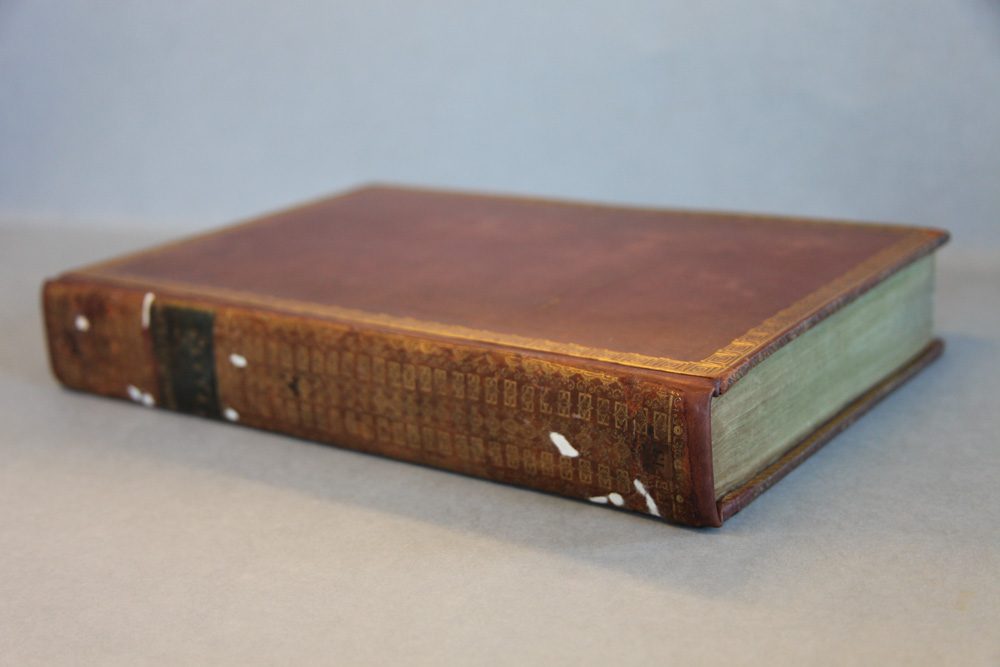

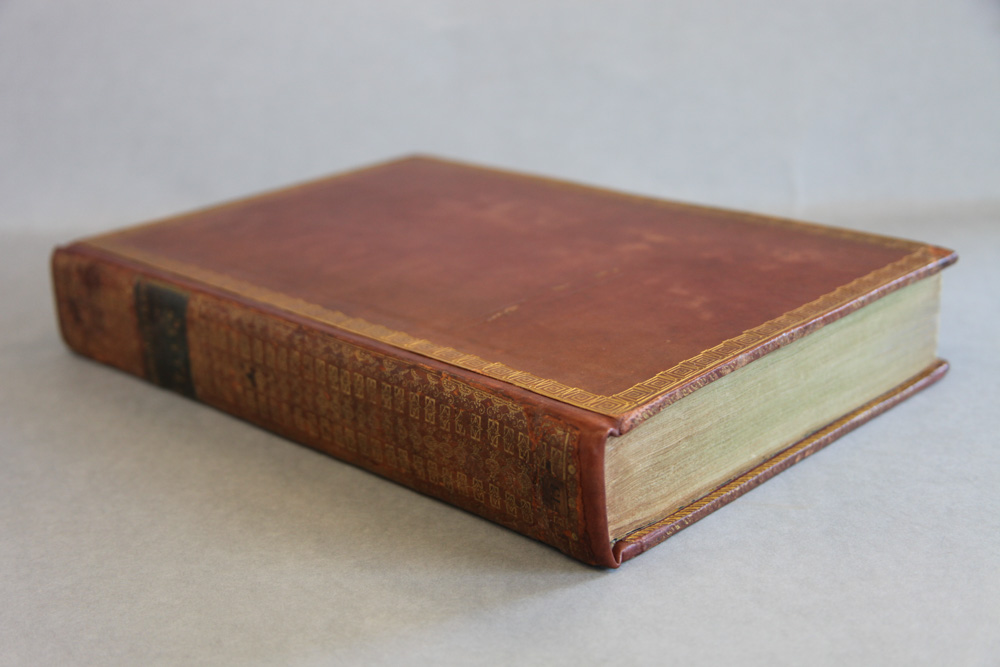

The book was in fairly poor condition. It had been rebacked at least twice and the last reback was creating tensions to the book. Boards were distorted, corners were worn, the front endleaves were detaching, the large strip of glassine paper supposed to support the title page was falling off and the pages were dirty and torn around the edges. There was definitely room for improvement!

Here are the illustrated stages of the conservation treatment:

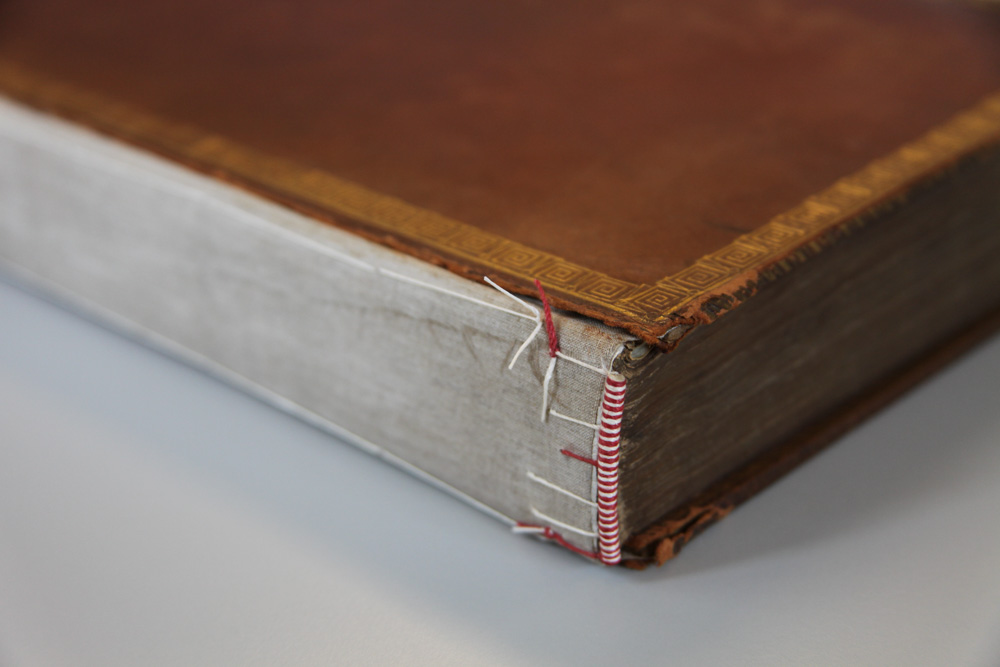

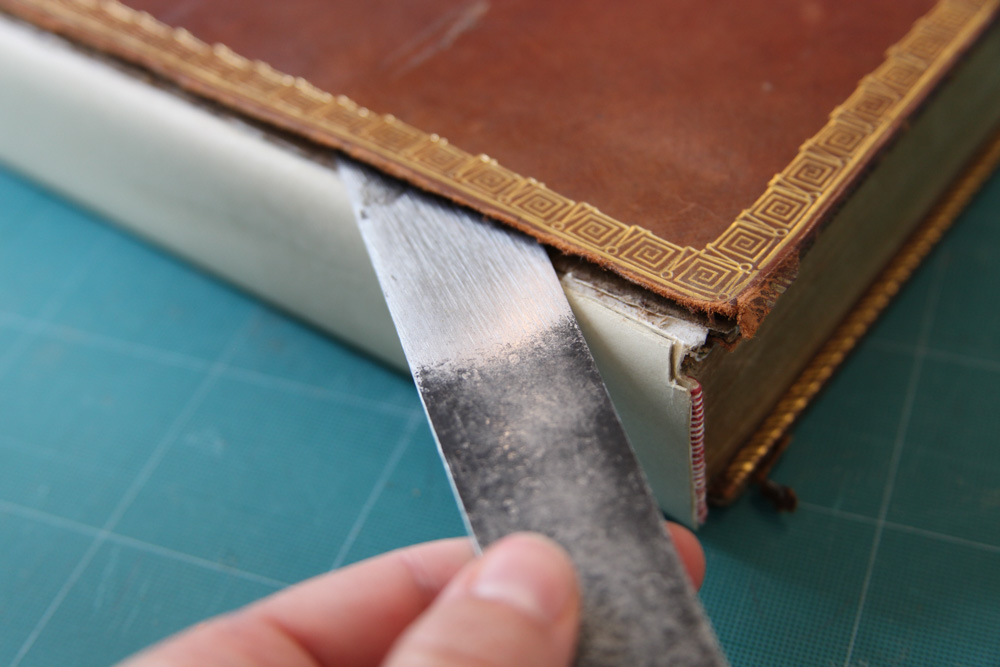

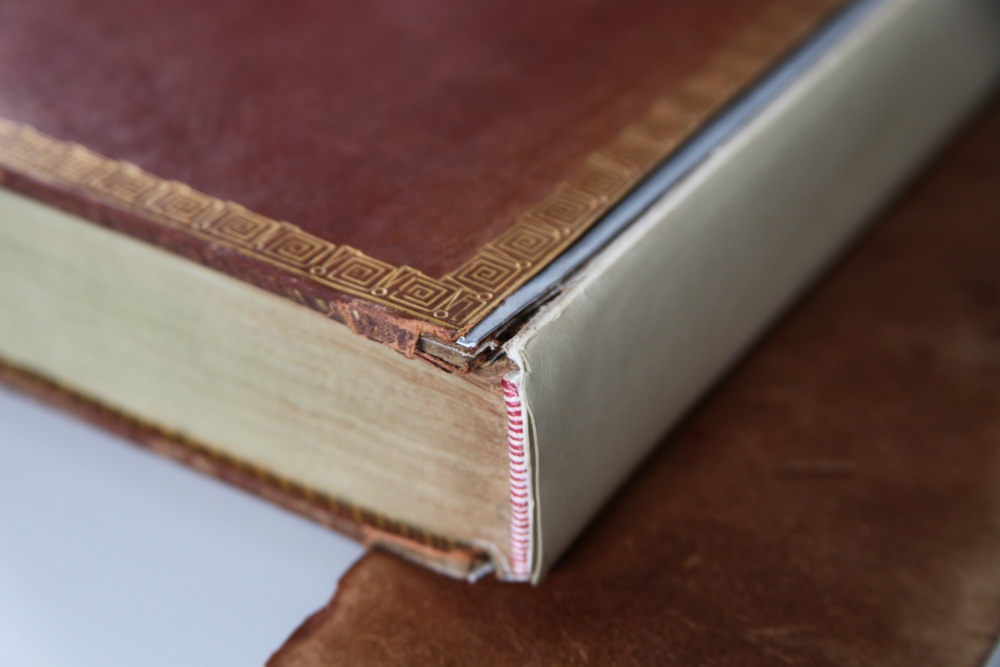

Removing the current reback, removing the thick layer of hard animal glue from the spine, and reinforcing the sewing with Japanese paper linings in the panels and linen braids over the sewing supports.

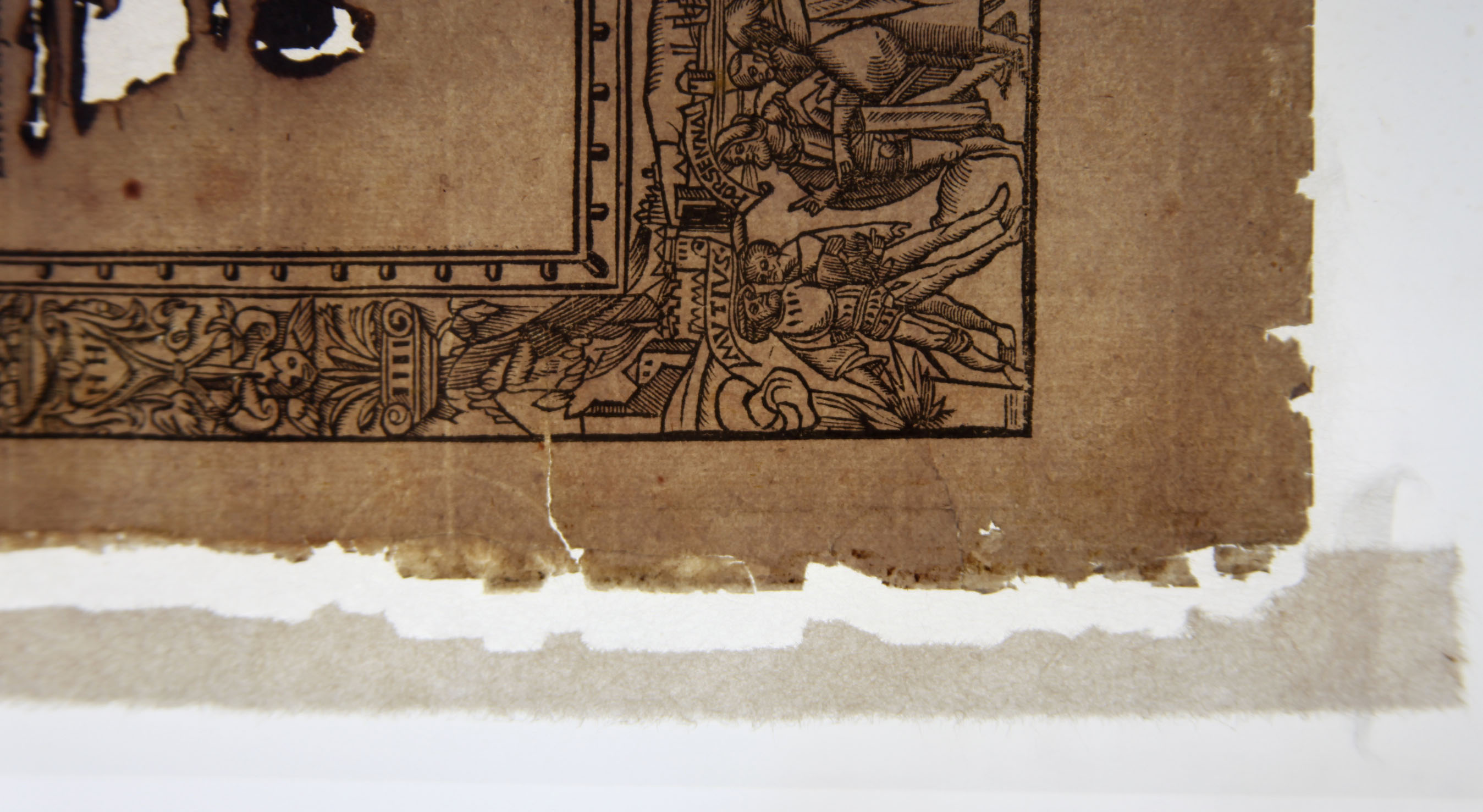

The glassine paper was removed mechanically.

Tears were repaired and losses filled with toned Western and Japanese papers.

Corners were reinforced and reconstructed. They were then covered with toned archival leather.

The waste parchment guard hooked around the front endpapers was cleaned so that the thirteenth-century manuscript writing could be revealed.

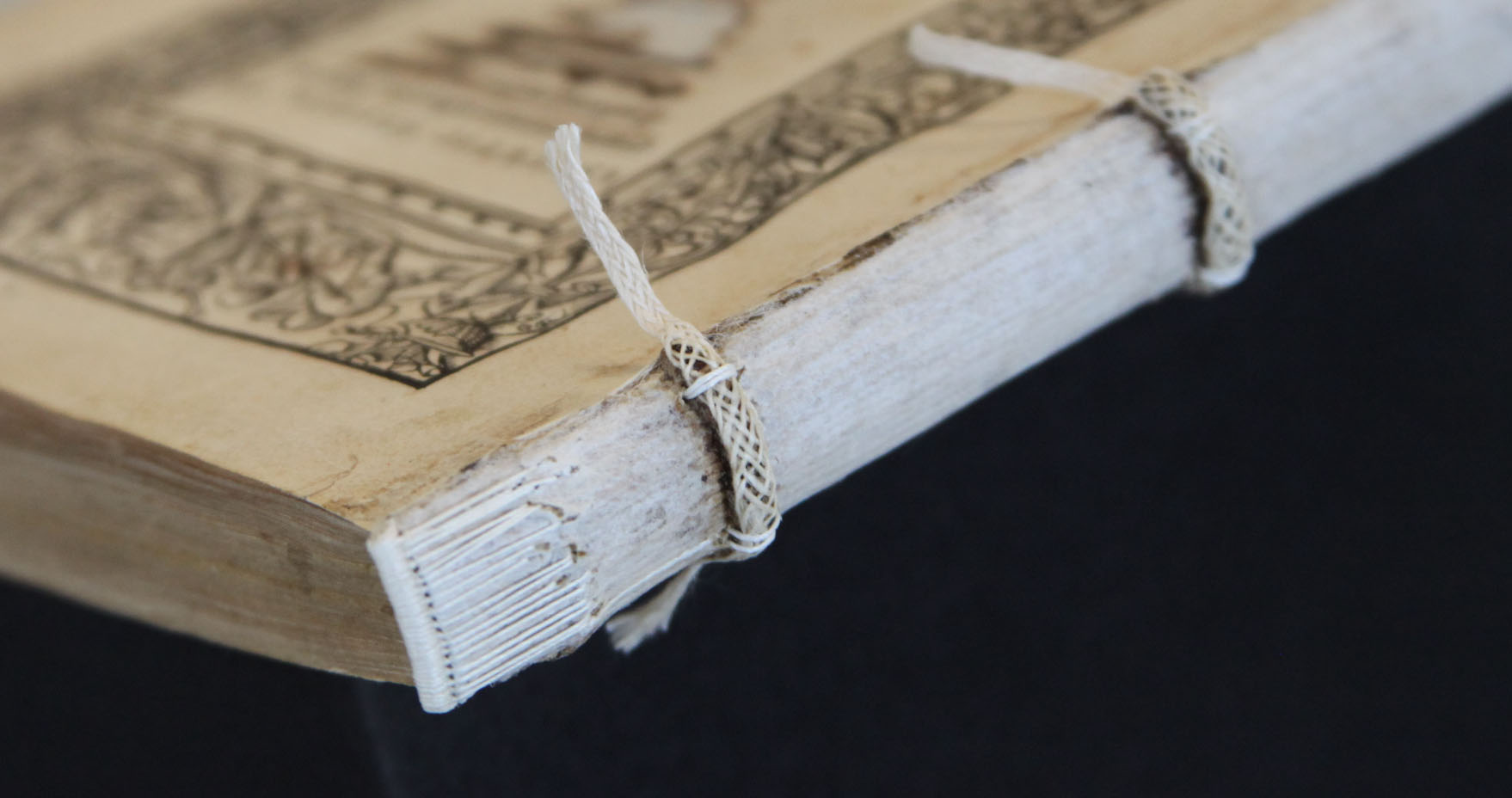

Margins were cleaned with a smoke-sponge. New back-bead endbands were sewn to reinforce the sewing. The detached leaves were guarded with Japanese paper strips and sewn back on to the textblock over the extended sewing supports using linen thread.

Boards were re-attached using the extended sewing supports. Finally, the book was rebacked with toned archival leather and housed in a bespoke drop-spine box.

Thanks to this collaborative detective work and the conservation treatment that followed, the book is now stable and well documented, available to researchers and ready to go on display!

Special thanks to Assistant Keeper Suzanne Reynolds for all her help in untangling the many mysteries of the book and bringing academic support to the project.