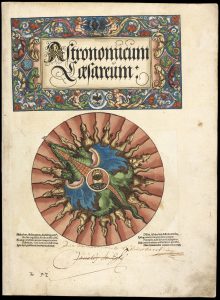

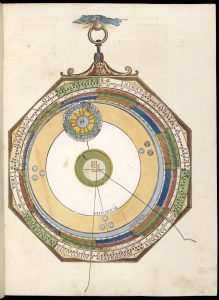

The Founder’s Library at the Fitzwilliam Museum houses an extraordinary collection. It charts the history of the printed book, from the first days of printing in the mid fifteenth century to artists’ books and productions of the private presses today. We are fortunate to have a copy of the Astronomicum Caesareum, one of the high points of sixteenth-century printing, as part of the collection. Printed in 1540 in Ingolstadt at the press of the author, Peter Apian (1495-1552), this magnificent book was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his brother, Ferdinand. It was designed to make astronomy accessible to those who did not have a high level of mathematical education. The reader is provided with volvelles – moving dials of paper attached to the leaves – throughout the book, the paper instruments allowing astronomical phenomena to be calculated.

Apianus’s work is based on the Ptolomaic system of astronomy, where the earth is assumed to be at the centre of the universe. However, within three years of publication, Copernicus (1473-1543) revolutionised thinking about the universe by suggesting that the planets orbit the sun. By the seventeenth century, Kepler (1571-1630) described the Astronomicum Caesareum as an elaborate waste of effort! Although scientific thinking has moved on, the book remains a superb artistic achievement: the typography includes a mirror-image font and decorative lay outs, the volvelles and decorative woodcut initials glow with rich hand colouring, and some of the pastel shades of paint are embellished with tiny golden particles, which sparkle in the light as the leaves are turned.

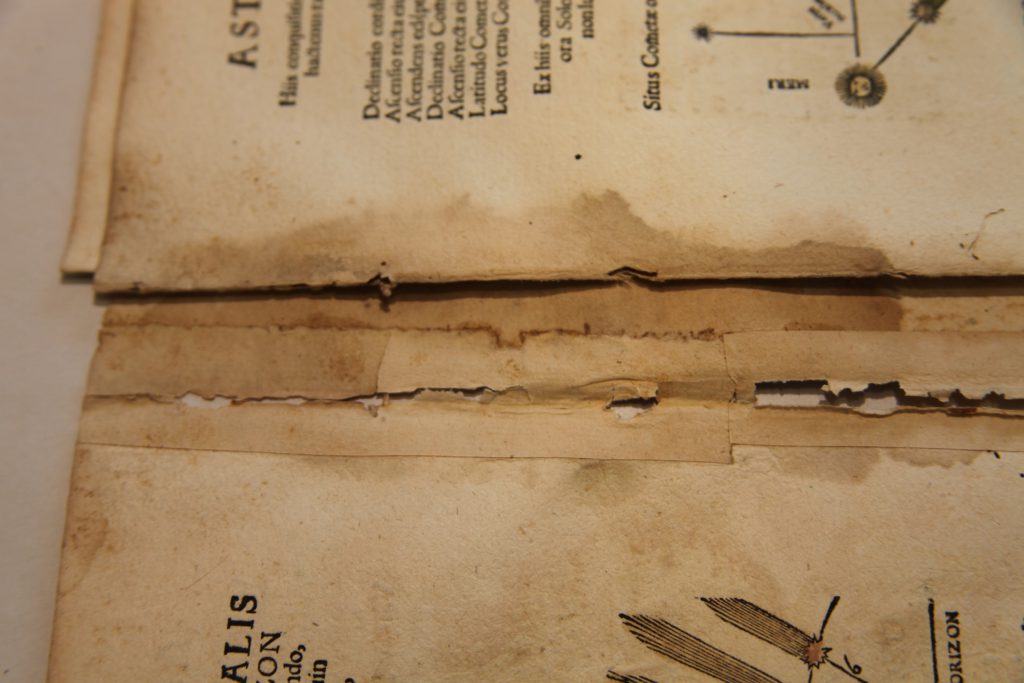

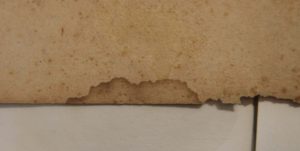

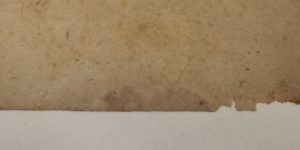

The book had suffered from damp and insect attack in the past and was repaired and rebound, probably in the early nineteenth century. Repair patches added at that time were very stiff and had caused the original leaves to crack along the edges of the old repairs. Over-large patches also obscured text. The binding was also breaking down, with the thin leather on the spine crumbling and the sewing threads either breaking or tearing holes in the spinefolds.

Over the course of the last year, the leaves of our copy of the Astronomicum have undergone extensive conservation work. This involved the careful removal of the old binding and heavy repair patches, the reduction of disfiguring water stains, and the repair of damage using Japanese handmade papers to make sympathetic infills.

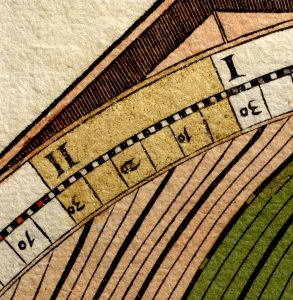

Our copy is one of the deluxe versions printed on very high quality paper made from rags and is remarkably well preserved. It is still possible to see the marks of the rope over which the wet paper was hung to dry, as well as blind impressions of type in blank areas, added to control pressure on the paper during the printing process. These un-inked letters are known as ‘bearer’ type.

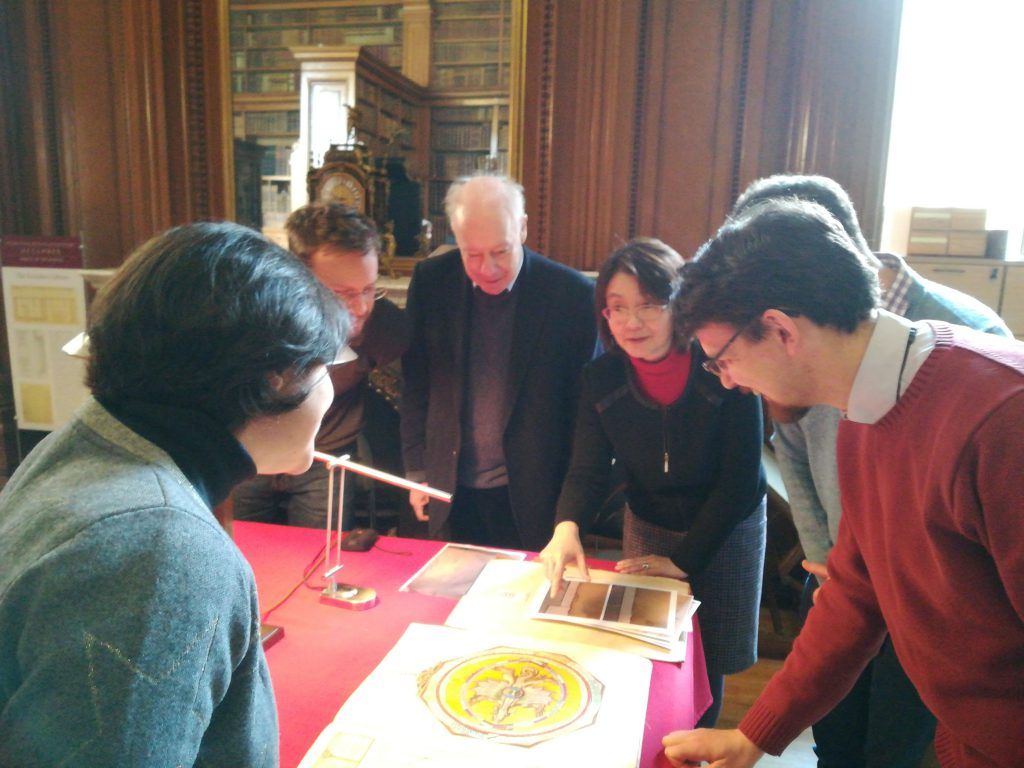

Recently, a team of historians of science joined us in the library to examine and discuss the book, as well as future possibilities for interpretation and digital access. Our scientists are also analysing the pigments in the colouring, and we hope to build up a more detailed picture of the materials and techniques used to make an extraordinary book.

Each leaf has now been digitised and we hope to be able to present the book and our research work on it in digital form in the future for new audiences to enjoy. The next stage of the project is to make a new binding for the book – keep a look out for a further blog post when the work is finished.

Edward Cheese

Conservator of Manuscripts and Printed Books

Fitzwilliam Museum