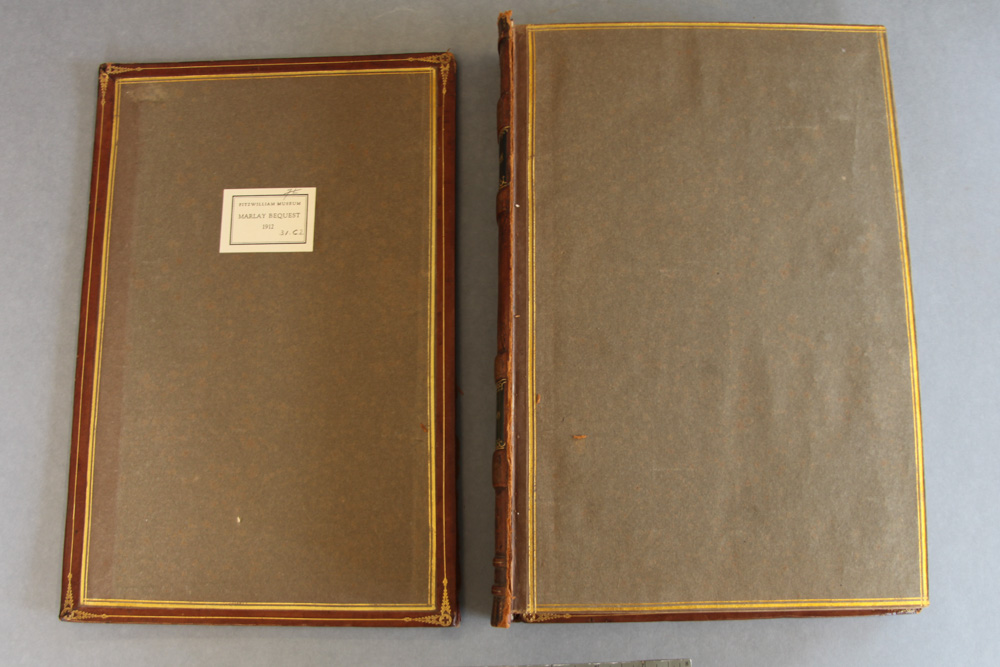

This June I was lucky enough to spend two weeks working with Richard Farleigh, Conservator of Works of Art on Paper, as I undertook my training placement at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. I have been living and training in Cornwall as a Books and Archives Conservator for just over a year now, having left my posts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in June 2017. It was a real joy to be able to return to the museum this year in a new guise, with new skills and a fresh perspective.

Carrying out my placement in the Paintings, Drawings and Prints Department (PDP) over a two-week period provided a unique opportunity for me to work alongside the Fitzwilliam’s paper conservators whilst also assisting the Department’s technicians with the installation of a new temporary exhibition. Whilst I cannot include in this blog post all that I have learnt, below I have picked out a few highlights from my time at the Museum. Before I tell my little story, I would like to thank the team for making me feel so welcome. It was a real pleasure to work with colleagues, old and new, and to gain such a breadth of experience through doing so.

My first week was largely spent assisting the Department’s technician team with the exhibition ‘Floral Fantasies’, now on display in the Shiba Gallery until 9th September 2018.

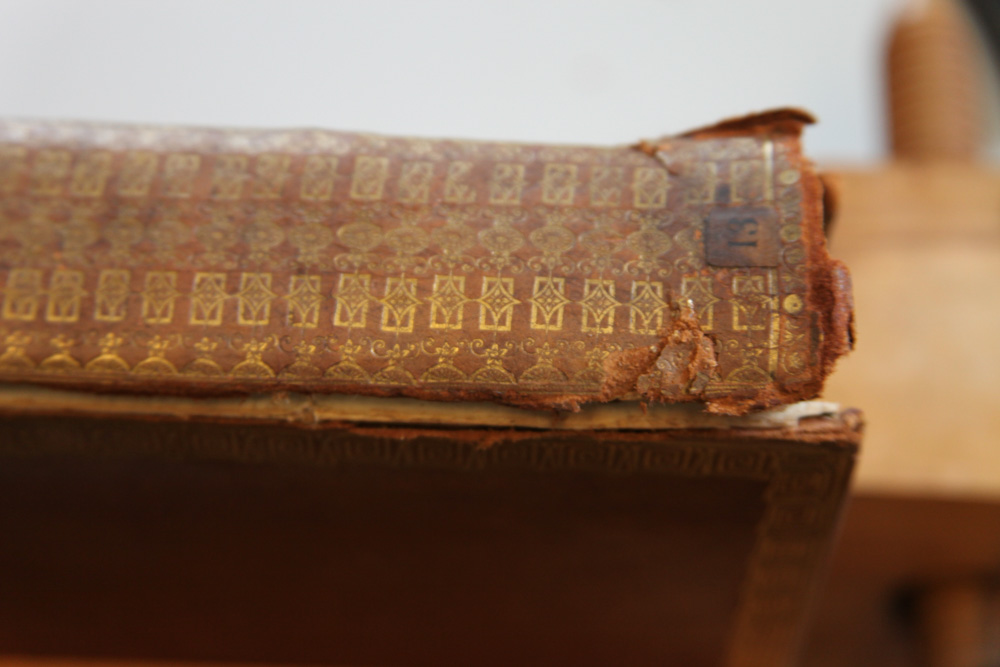

It was hugely valuable for me to work on this installation due to the range of objects and materials involved, each presenting its own challenges for mounting and display. It was exciting to see innovation at work in the Museum, particularly in terms of new mounting techniques and the use of acrylic to create bespoke cradles for the paper-based collection and the museum’s precious miniatures.

Coincidentally, my placement fell just at the moment a large consignment of some 80 art works, a loan show, Degas: A Passion for Perfection returned from the Denver Art Museum, USA. I assisted with the unloading and then helped the technician team return the full transit crates to one of the Museum’s picture stores.

The Museum had used a number of shock loggers, packed inside selected crates which monitored shock magnitude in real time.

Some of the works, be they pastel drawings or three dimensional sculptures, are inherently fragile. Information from the Shock loggers was relayed to designated recipients who were then able to monitor levels of shock and/or excessive vibration during the long journey.

I also assisted the conservators and technicians in unpacking several of the crates and then helped to condition check a number of Degas drawings.

It was interesting for me to understand how the Museum manages its various loans and to work through the procedures for condition checking. Later in the year in Cornwall I will be delivering a training session regarding best practice for display and will certainly be able to include many of the tips that I picked up whilst working in the PDP Department.

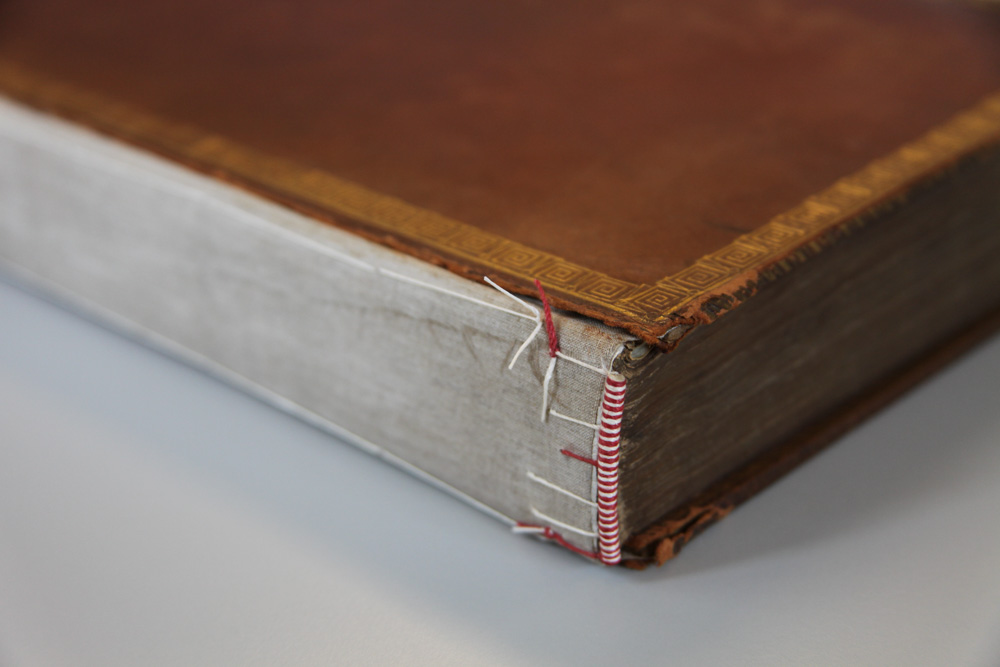

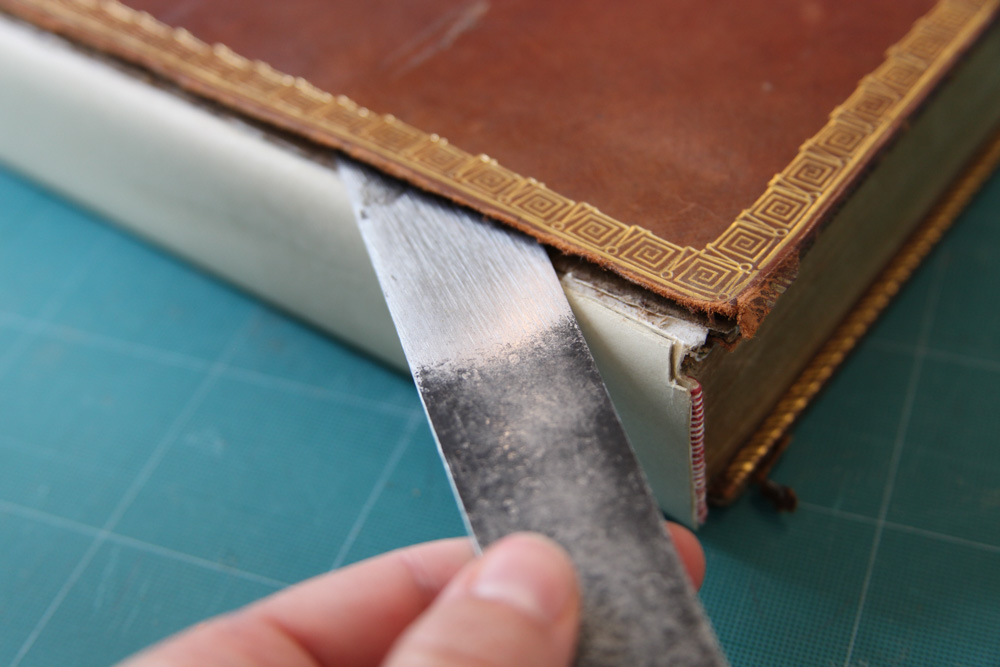

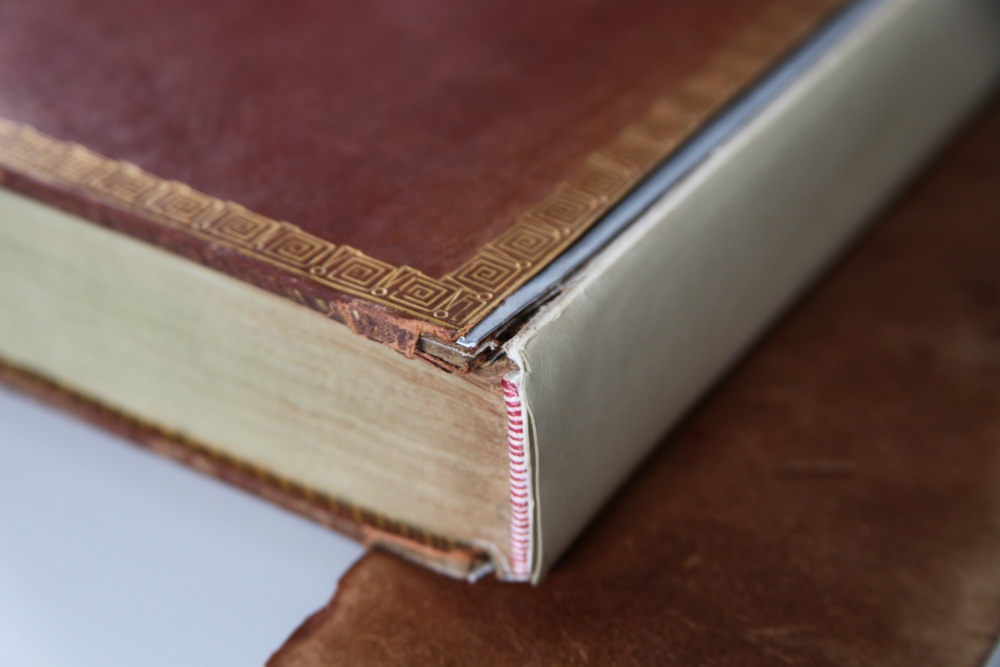

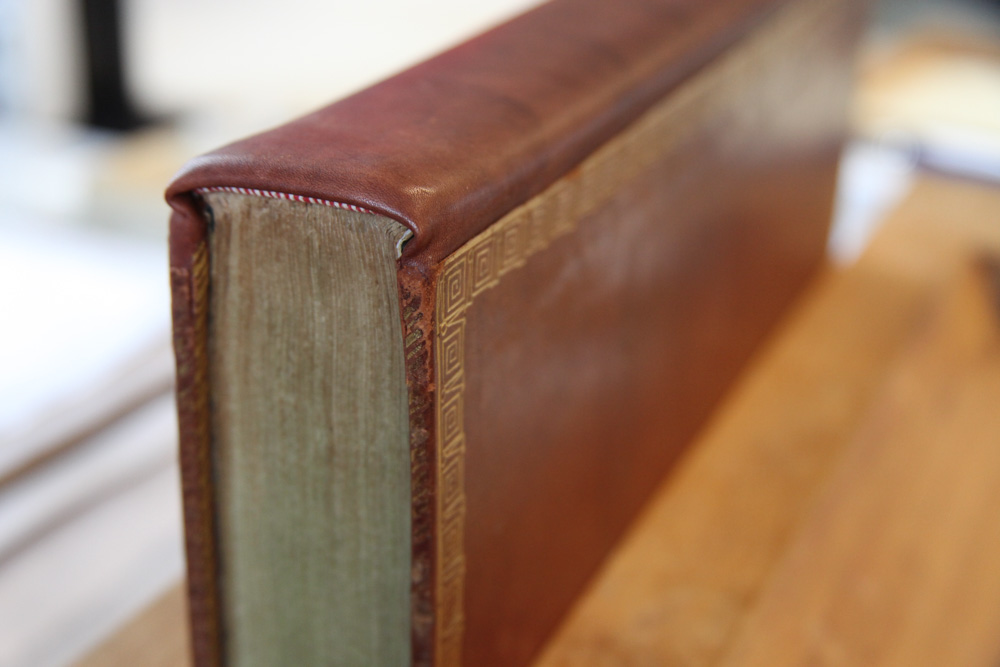

During my second week I was able to spend time at the bench in the conservation studio with both of the PDP paper conservators. With the Conservator of Prints, Harry Metcalf, I tried my hand at inlaying prints from parts of the collection currently not on display.

I also worked with Richard Farleigh on the mount cutter to learn more about the various house-styles for mounting up drawings. I made a mock-up of a mount for my own print and practiced other techniques using Japanese paper hinges. As exhibition preparation falls outside the remit of our conservation studio in Penzance, it was extremely useful for me to exercise my mounting skills. I now understand how to provide safe and lasting housing for paper-based collections, and how to select the most appropriate display methods.

As I came to the end of my placement, it was a real joy to work in the studio with Rosie Macdonald, a contract paper conservator. In collaboration with the Applied Arts conservators, Rosie is conducting a survey of the condition and the conservation needs of the Lennox-Boyd collection of fans, a recent bequest of 435 folding fans, 10 screen fans and 178 single leaf fan designs. I helped with the survey and the cleaning and packing programme. Fans are complex objects often made from a variety of materials including paper, bone, gems, metal leaf and textile. Their conservation and storage needs are challenging, as Rosie explained.

Careful thought has also been given to the method of packing. Each item is wrapped in acid-free tissue, folded (importantly not rolled) in such a way that the fans are still partially visible through a layer of tissue, whilst also being supported by multiple layers of folded tissue underneath, forming a cushion.

My return to the Fitzwilliam, albeit brief, has really allowed me to supplement my training in Cornwall by broadening my skills in both paper conservation and exhibition planning and preparation. I would like to give special and sincere thanks to Richard Farleigh for organising my placement and for taking time out of his busy schedule to pass on his skills and provide opportunities for me to collaborate with colleagues.

Until next time Cambridge….

Hollie Drinkwater

New Starter Trainee

PZ Conservation C.I.C.