How LEDs are now very much earning their keep. Conservation viewing aids and other useful pieces of equipment.

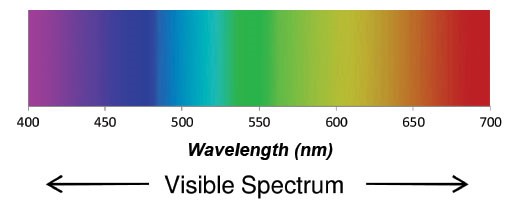

Definition of ‘light’: The natural agent that stimulates sight and makes things visible; the key words here being ‘makes things visible’.

Definition of to ‘illuminate’: to enlighten, as with knowledge, to make lucid or clear.

With such a large, diverse and dynamic collection here at the Fitzwilliam1it is hardly surprising that a lot of time is given over to preparing new displays, reviewing items destined for loan and supporting, at times complex in-house exhibitions.

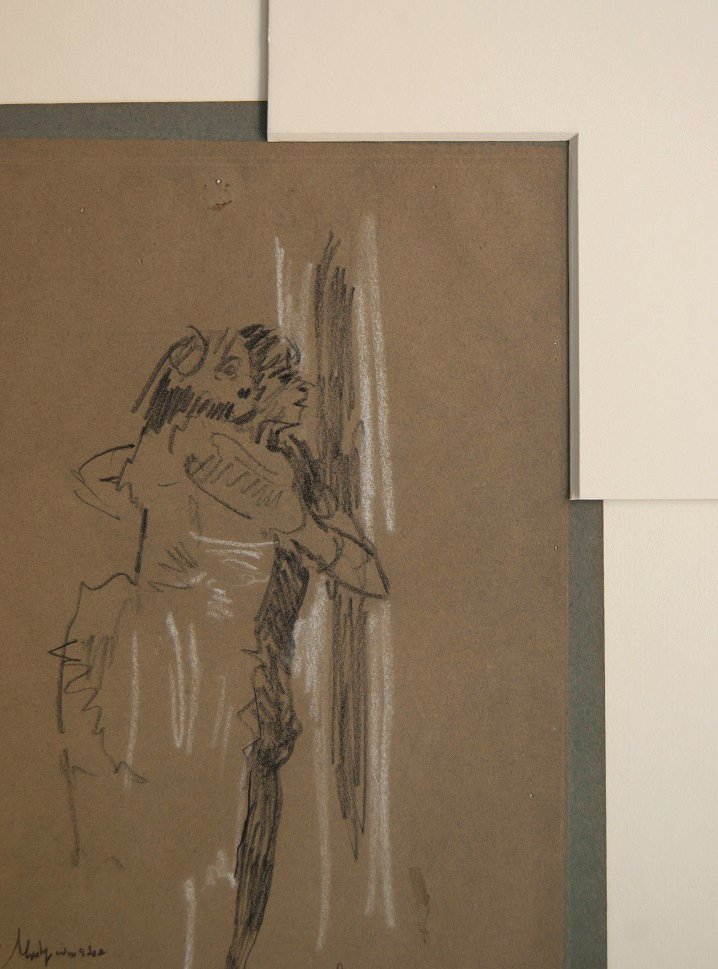

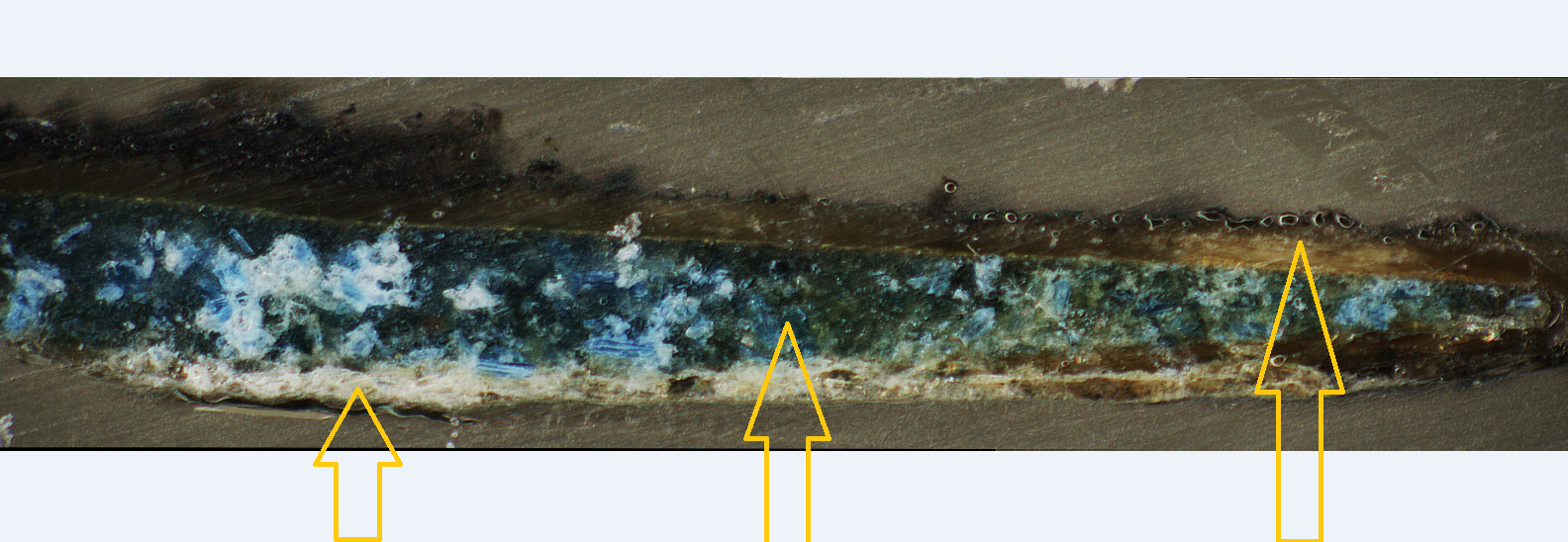

Conservators are required to examine objects extremely closely and quite a lot of their time is spent carefully recording this information. Assessments are made with regard both damage and decay and then to diligently note perceivable change, especially over time. Furthermore, we must be able to establish the construction of an object, the materials that have been used, such as paper and drawing media, and in some instances even the order in which these have been applied.

Although light can be extremely damaging to a wide range of museum objects, its power with regard to illuminating collections can be fascinating and at times, revelatory. As such, both good light and good optics are essential.

Stand alone inspection lamps

To help in these tasks, the museum has recently acquired several stand – alone LED photographic lamps 2. These have replaced older fluorescent lamps which by comparison are somewhat harsh, one directional and at times prone to heating up.

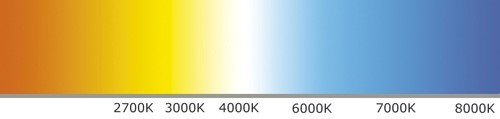

Useful features include: an ability to adjust both the levels of illumination and colour temperature and integrated rechargeable batteries, which offer the unit much greater flexibility of use.

For conservators, the technology is now very much out there and the options available are multiplying all the time. To some extent, the process of selection will be determined by personal preference and in many cases, the cost. Speaking from experience, investing in a good stand (one that is both stable and mobile) will pay dividends. The wheels on ours seem to have a mind of their own and tend to travel in only the one direction!

Hand held LED inspection lamps

The Docter Aspherilux Midi rechargeable LED Torch 3

German-made and the quality really shines through.

German-made and the quality really shines through.

A compact torch which gives bright, directional light of even intensity. The metal casing is robust, the body is well balanced and the unit contains integrated rechargeable batteries. The only problem you may have with this particular torch is ‘holding onto it’. In our museum, at very least, useful things become popular with others!

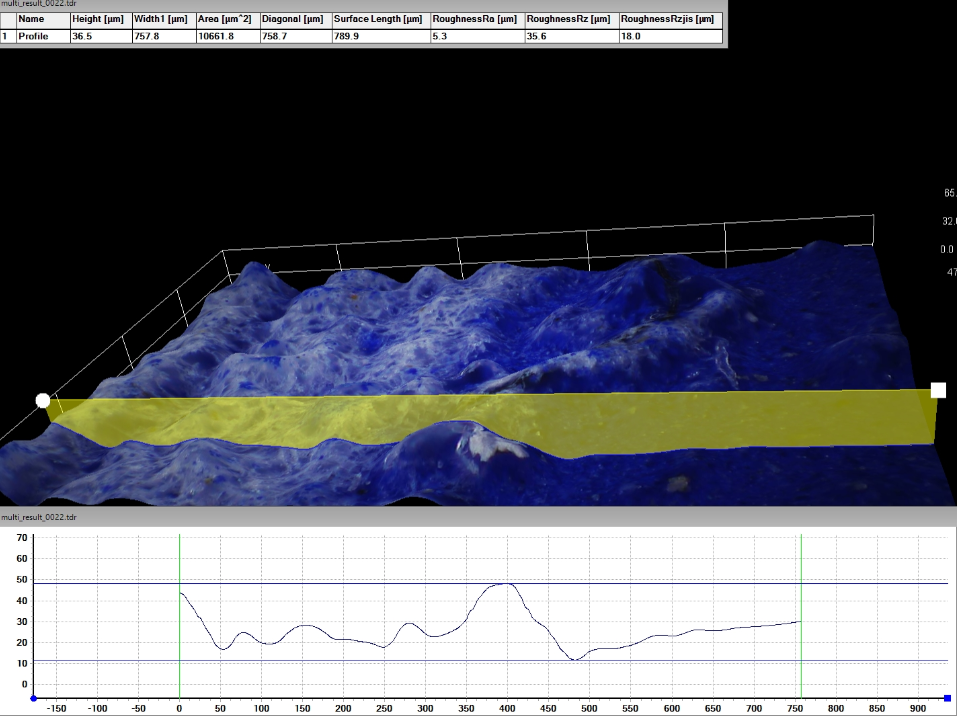

This clearly shows the power of ‘raking light’ in revealing the paper undulations, embedded creases, ingrained dirt and other interesting surface textures. Invaluable!

Shown below is a portrait miniature of Charles, 1st Marquis Cornwallis (1738-1805), No 3922. Watercolour on ivory, by John Smart (British artist, 1741-1811) within a decorative gold locket, glazed. Dimensions: 67 x 52 mm.

The black arrow above shows a passage of glass clouding and although subtle, this is important, being indicative of the onset of glass disease4. If this condition is left indefinitely, especially in a poor environment, the sequence of deterioration would become very much more dramatic. As such, by having noticed the change and ideally acting accordingly, this is an important first step in any good preservation plan.

Ultra Violet LED lamp5

On occasion, examining an object under Ultra Violet light can be extremely rewarding as illustrated by the 16th century portrait miniature, shown below. In this case the yellowy – green fluorescence indicates passages of loss, earlier damage and discrete later additions. This particular ‘visual marker’ is indicative of a 19th century pigment, Chinese White (zinc oxide)6.

Portrait miniature of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales by Isaac Oliver (British artist, 1556(?)-1617) 3903. Watercolour on vellum laid to card. Dimensions: 52 x 40 mm.

Magnifiers

An Optivisor is a useful and inexpensive viewing aid, costing approximately £30-50. This is the sort of thing that one often reaches for whilst inspecting an object at close quarters and is commonly used by paintings conservators engaged in detailed image reintegration -restorations.

Various lenses are available offering different powers of magnification and are easily interchanged. Personally, I have found x 4 most helpful for some of the more detailed conservation tasks.

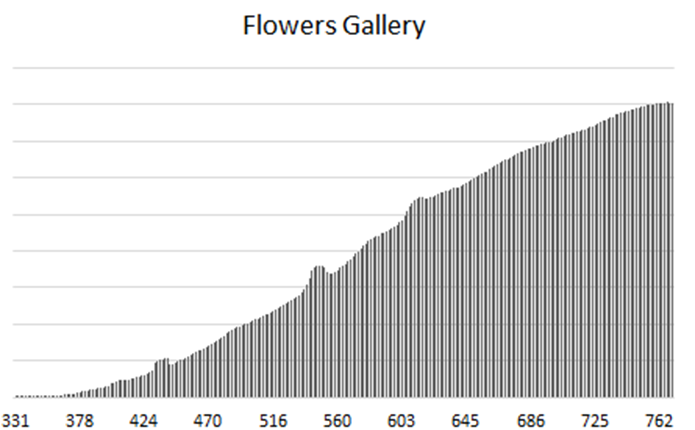

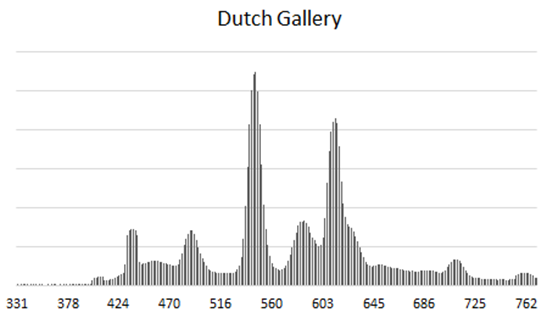

In recent months here at the Fitzwilliam we have been taking a closer look at many of our miniature paintings7and for this task, I have found a small hand-held magnifier especially useful8.

Portrait miniature of an unknown man, PD.958-1963. Watercolour on ivory by John Smart (British artist, 1741-1811) within a decorative gold locket, glazed. Dimensions: 38 x 32 mm.

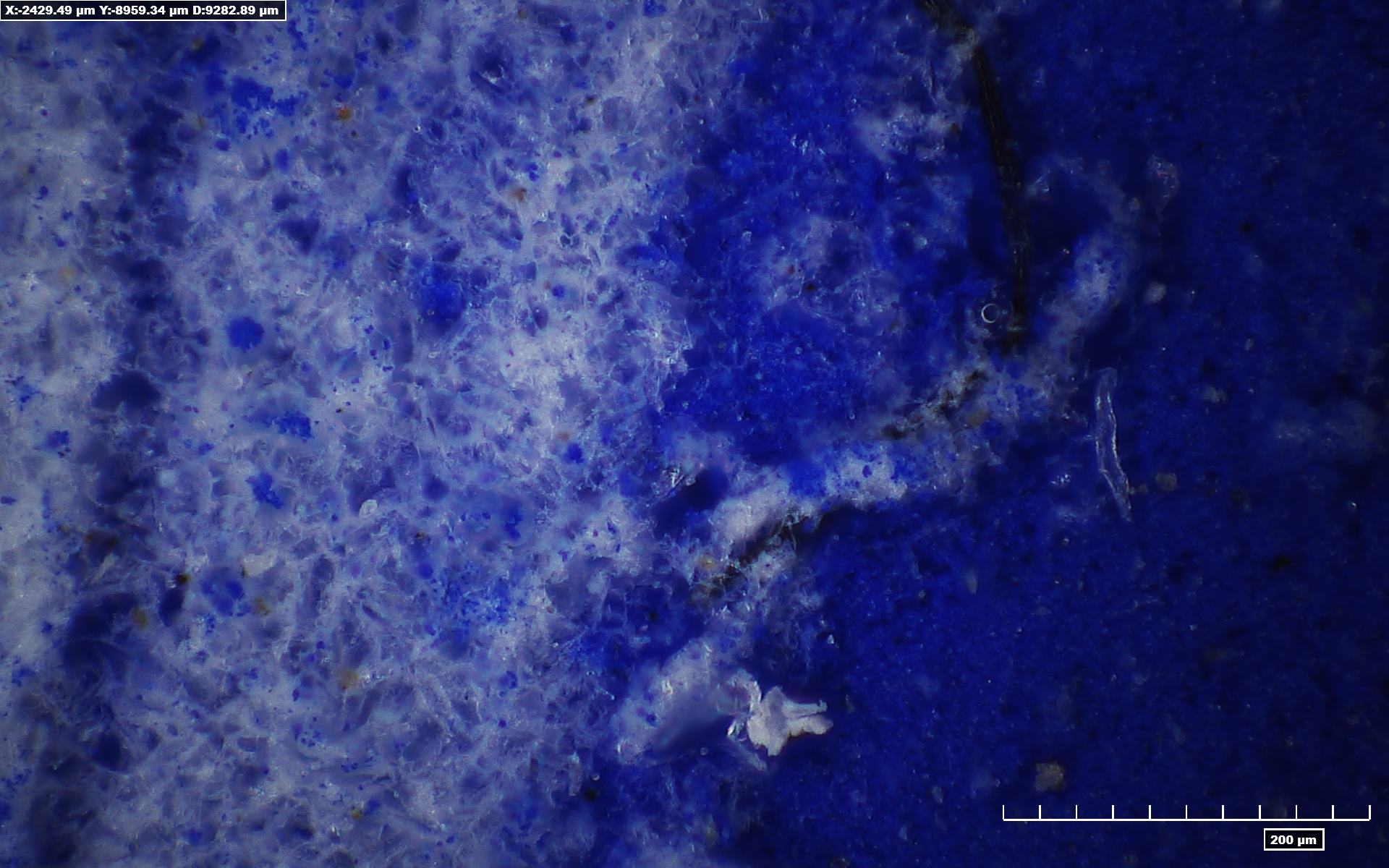

Examining such small works as these under magnification and in good light, helps enormously in their interpretation. Close inspection is invaluable and may reveal all sorts of ‘collection care issues’; such as friable media and/or loss, the onset of glass disease or perhaps even, invasive mould growth (see the detailed image shown below).

Portrait Miniature of Sir Joshua Reynolds by James Nixon, British artist, c.1741(?)-1812, No 3800. Watercolour on ivory, within a locket, glazed. Dimensions: 80 x 64 mm.

Scale in life: 40 x 60 mm (detail)

Under closer scrutiny, surface mould growth is clearly visible. Spotting this type of damage and taking the necessary action (ideally addressing the mould and being especially vigilant with regard ‘storage conditions’) is important, in any progressive collections care plan .

Conservators are naturally inquisitive creatures and often, through necessity, have had to evolve and adapt. The profession is relatively small and sadly, all too often poorly resourced. As such, borrowing ideas from others is especially satisfying and all the more so when this saves a little money.

LED Light panel – light box

By way of example our studio recently purchased an LED ceiling light panel9,a chance find at a local electrical outlet. Although most frequently used in schools and hospitals, this even light source has now become our ‘go to’ studio light box.

Transmitted light (light shone through a surface, such as a paper) is especially helpful in revealing certain characteristics that otherwise may remained hidden, such as a maker’s watermark or perhaps even, the date of manufacture.

M.219-2015: 18th century Italian chinoiserie fan. One of 600 or so, rich and varied fans recently acquired by the Fitzwilliam (2015)10.

As conservators we look for clues with regard the paper type, the process of manufacture, the probable age and perhaps even, a place of origin. This not only helps in our better understanding an object it may sometimes lead to more precise authentication.

Below is a watercolour by JMW Turner, photographed in day light.

When viewed in transmitted light the paper shown above is clearly wove11 and looking more closely, a maker’s watermark ‘J Whatman 1834’ can be seen, which is both of help and significance. Turner is known to have visited Venice on at least three occasions, in 1819, 1833 and 1840, although recent research has suggested that he was also there between 1835 and 1839. The light shining through the paper reveals an extensive inscription written on the back of the watercolour (possibly in Ruskin’s hand) and also gives useful insight into Turner’s working methods where he has scratched back the paper, creating highlights of both the Venice skyline and turbulence seen in in the sky and breaking waves.

Dated watermarks do not prove the date of production but do provide a reference point of sorts, and it would be reasonable to assume that the work by Turner shown above could not have been produced any earlier. It could, however, have been produced several years later. Some artists are known to have preferred using a seasoned or aged paper, whereas others may have returned some years later to work up an incomplete sketch.

I hope that some of the illustrations presented above are of help and may stimulate others to look more closely and with that all-important ‘questioning eye’.

Acknowledgement: My thanks go to several kind colleagues for reading the text, helping with IT issues and for gently nudging me back on course.