International courier trips are often seen as one of the benefits of a museum career. When objects are lent to museums overseas, they are usually accompanied by a member of the collections team to oversee their safe transport, handling, and installation at the venue. It’s an amazing chance to go behind the scenes at some fantastic museums in lovely locations, and you might just squeeze in a few hours’ sightseeing somewhere exotic… Of course, it’s not all glamour! You can just as easily be spending long hours in a cargo shed at an airport, driving long distances in a lorry, or get stuck in customs, without many opportunities for a break or a meal, while making sure your precious artefacts are supervised at all times. But COVID has changed all that; and that is why in June I completed my first ever ‘virtual courier trip’, to the Kunstmuseum in The Hague.

The Fitzwilliam has loaned 15 pieces of English Delftware pottery to the Kunstmuseum for a show called ‘Royal Blue: William and Mary’s Finest Delftware’. The objects were sent out to The Hague in early March, accompanied by Tim Matthews from the Applied Arts department at the Fitz. They had just arrived at the museum when the whole of the Netherlands went into lockdown and Tim had to rush back to the UK to avoid becoming stranded. All plans to install the exhibition were abandoned and the ceramics were placed in store in their travelling crates without being unpacked.

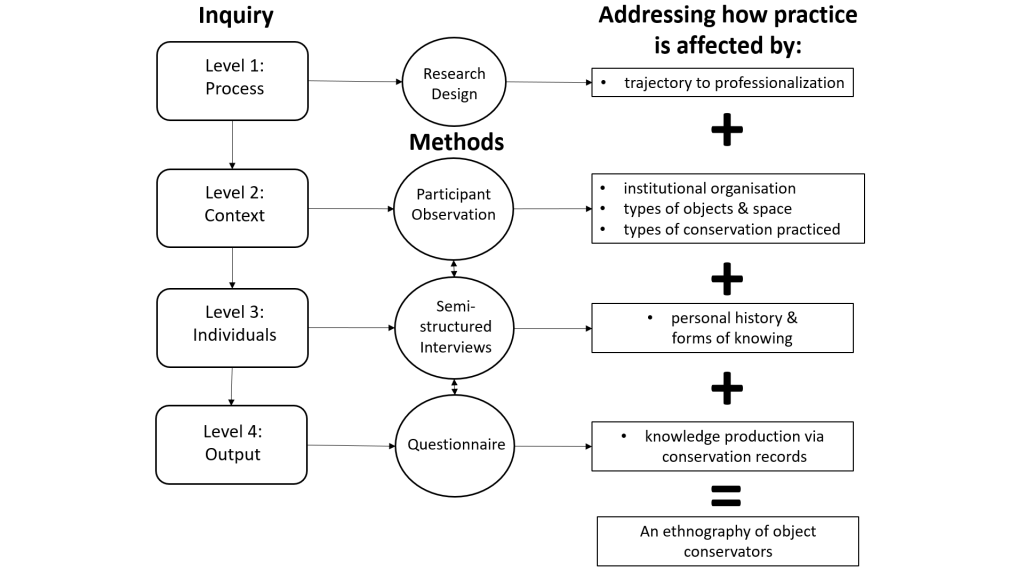

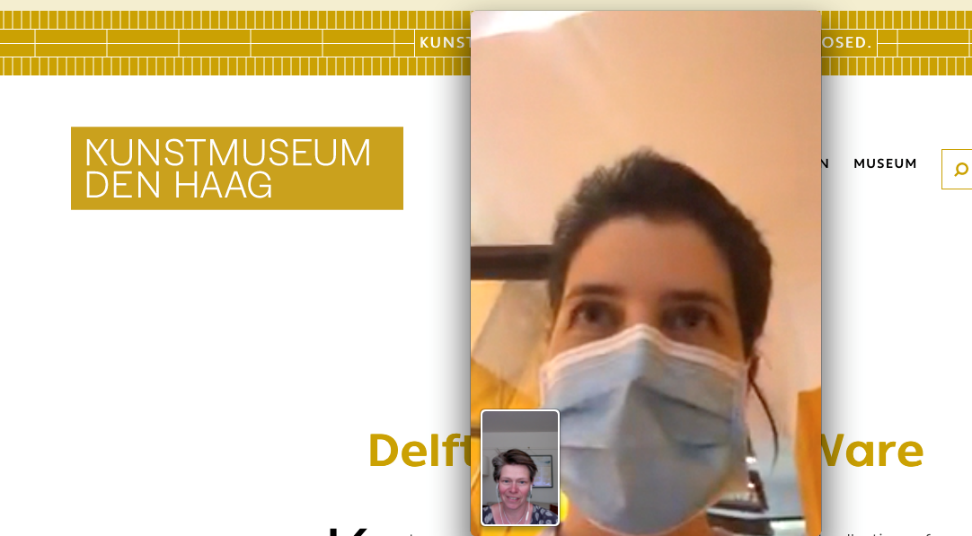

Ten weeks later, the Kunstmuseum was planning to reopen and install the exhibition. But many institutions have lent objects for the display, sometimes from countries which, like the UK, were still in lockdown, and sometimes from museums with staff on furlough. For the exhibition to be possible, we all had to adapt our usual procedures. In this case, we decided to do the courier trip via a video call.

We used FaceTime, which meant I could follow what was happening in The Hague and also look at the loan documents I needed on the computer. (Other platforms could have worked in the same way for a PC.) At the other end, curator Suzanne Lambooy, conservator-restorer Maud Schermer, and the conservation assistant team used phones to video every moment of the process in a live session.

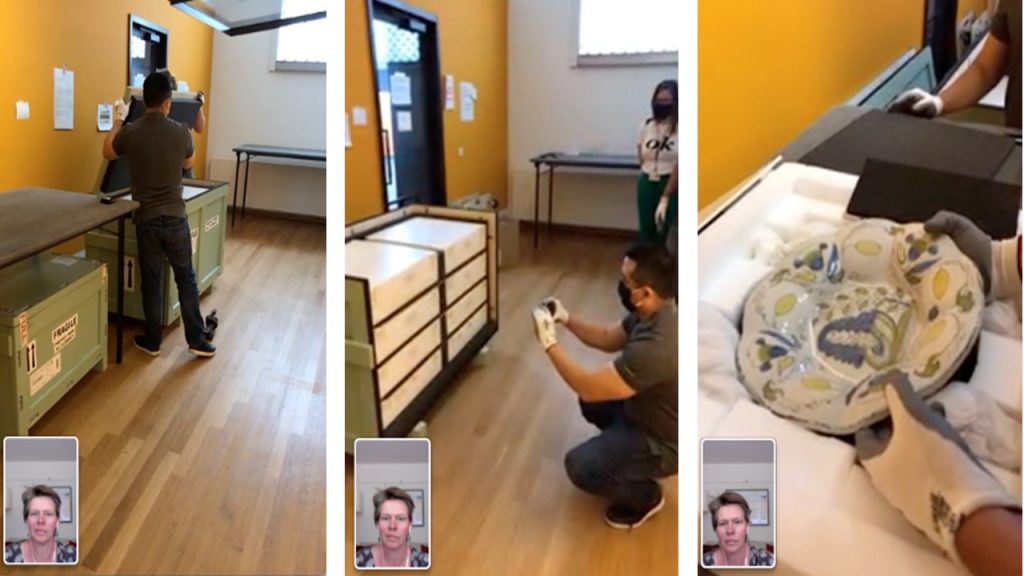

After introducing ourselves, we got on with unpacking the objects. The conservation assistants opened the crates and started to unpack, photographing every stage to make repacking easier at the end of the exhibition, and to have a record of anything untoward that might have happened during the journey. Luckily everything was in perfect order.

All the ceramics were laid out on padded tables next to the display cases and Maud started to check them over. The condition of objects when they leave the Fitzwilliam is documented thoroughly in condition reports and photographs, so Maud and I checked each piece carefully against the records to make sure that there was no new damage. Delftware is very fragile and even well-preserved examples almost always have lots of cracks and chips. Delftware needs to be handled very carefully because it is so easy to damage. Happily, all the staff at the Kunstmuseum are very familiar with this material, and everything they did was exemplary! Maud is a specialist ceramics conservator so was also the ideal person to be doing the real-life condition checking.

Looking at the objects in detail was one of the highlights of the experience for me. All of them are decorated with images of William and Mary, who ruled both England and Holland from 1689 to 1702. The pieces are hand-painted and have quite stylised motifs – for example, the things which to me look a bit like lemons are actually intended to be tulips:

Similarly, the heavy blue clusters of circles topped with birds on this plate are actually a very stylised version of the rock-and-bird motifs found on some Chinese ceramics which were popular in the same period.

It was also fun to compare the images of the king and queen, which varied from the frankly jaded…

to the quite frisky…

and, in this case, reminded us rather unfortunately of Jabba the Hutt!

All the designs are unique and quirky, and I could have spent a lot longer enjoying their different characters; but we had to get on with installing the objects in the displays. Curator Suzanne and conservation assistant Bao worked on arranging the dishes and jugs in the display cases, which were painted in William and Mary’s signature orange colour. The blue-and-white ceramics, with their dashes of yellow, really sing out against this background.

Soon the displays were finished and the cases could be closed down and locked: they won’t be reopened now until the exhibition closes and it is time to pack everything for transport home.

This adventure in ‘video-couriering’ went amazingly well, not least because the members of the Kunstmuseum team were very experienced and professional, and also lovely people to work with. We had a few challenges with the signal dropping out and batteries going flat – video calls use masses of power so the phone used for the session needed to be on charge for quite a lot of the time. (A portable battery charger would be a big help here!) The video quality is never brilliant so it is also crucial to have good photos of the objects when doing the condition assessments: the main benefit of the video at the condition-checking stage is to help make sure we are all talking about the same thing.

Typically, exhibition installations can get pretty hectic, with precision timing needed to install pieces from multiple lenders in a short space of time. The scene at the Kunstmuseum was almost eerily quiet by comparison. This was partly because only about 15% of their staff were on site, to maintain social distancing as the museum gradually returned to work. Naturally everyone was also wearing a mask and gloves at all times. I asked how they were finding using video to work with ‘couriers’. On the plus side, the exhibition space itself does not get too crowded, and if more than one lender needs to supervise a particular display case being closed for the exhibition, they can attend virtually at a time to suit all. This makes some of the logistics easier to arrange, and reduces time pressure. The logistics of organising even virtual installations were tricky at the time because so many museums were closed and had their staff on furlough, but this has now eased.

This experience has challenged my assumptions about couriering objects on loan in a very positive way. It is encouraging to realise that by being flexible we can develop safer (at the moment) and also more environmentally and financially sustainable procedures, without compromising the safety of objects travelling on loan. And collaborating with the lovely Kunstmuseum team online was almost as refreshing as actually going to The Hague after so many weeks of working from home!

Sophie Rowe, ACR

Conservator of Applied Arts

Fitzwilliam Museum