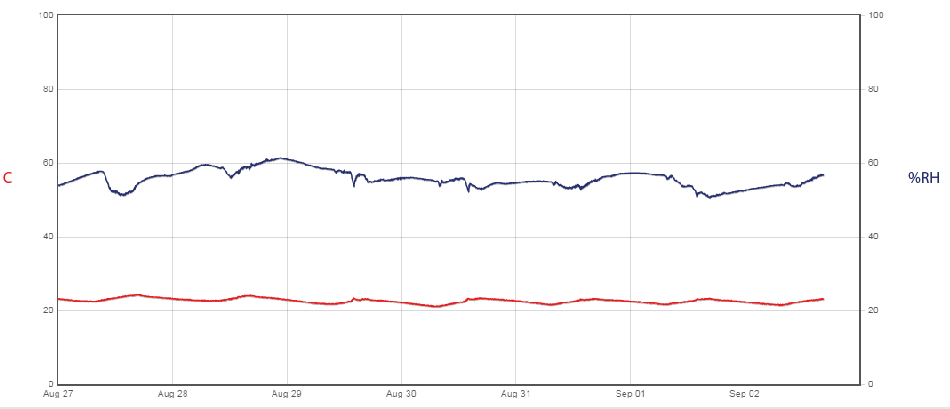

On 6th January, I started in an exciting new role as an Institute of Conservation (ICON) Preventive Conservation Intern at the Fitzwilliam Museum. I quickly became involved with assisting Helena Rodwell, Assistant Conservator (Collections Care), with the regular environmental monitoring in the Museum and have been participating in workshops to improve and update the Museum’s emergency plan documentation and implementation.

It is imperative that museums assess and mitigate risks to their collections and have a clear, concise and useable Emergency Plan for use during emergencies, where there is potential for confusion when normal working patterns are disrupted

Emergency Planning: Risk Management and Threats

Risk Management refers to the practice of identifying potential risks, evaluating them, and establishing measured, precautionary steps to halt or reduce the risk. Risk is an assessment of both the probability or likelihood of a specific event occurring and the magnitude or extent of its impact. Robert Waller states that ‘the estimation of the magnitude of… [a] risk is highly dependent on statistical information regarding the probability of the event.’

Unfortunately, there have been many high-profile museum disasters recently, from fire at the Glasgow School of Art to flooding at Pontypridd Museum in South Wales. As institutions that safeguard collections for future generations, museums have to be prepared for potentially serious occurrences.

Potential threats take many forms, but include:

- Pest Infestation – the inundation by pests, such as the organic-object-consuming Vodka beetle, within a gallery or museum store

- Fire – a minor or major ignition affecting museum collections or buildings

- Flooding/Abnormally High Relative Humidity – water-damage or dampness caused by natural (e.g. overflowing rivers), mechanical (e.g. leaking pipework) or incidental (e.g. water-damage from a fire hose) factors

- Theft/vandalism – the premeditated taking of or damage to museum collections

- Terrorism and intentional violence for political or religious reasons

Emergency Plans and Staff Development

Emergency plans vary based on the size and complexity of the individual museum. Staff are well-suited to develop an emergency planning document, as they have intimate knowledge of the buildings and collections and are acutely aware of potential risks.

One of the benefits of staff being the primary drivers in the production of an emergency planning manual is that the documentation can be continuously reviewed to reflect changing exhibition spaces, new collection objects, loans, or major building redevelopments.

Emergency Planning Workshop: Objectives

To assist with an emergency situation and to enable staff to act swiftly to minimize damage to buildings and collections, the Fitzwilliam Museum is holding a series of workshops to review and update the emergency manual and to ensure a large group of museum staff shares the responsibility of the manual’s execution. The workshops also aim to build the confidence and knowledge of the emergency team through continual training and exercises.

The most recent workshop (fig. 1), facilitated by Rosie Forrest, Documentation Coordinator, Sophie Rowe, UCM Conservator, and Helena Rodwell, had the aims of:

- Understanding each individual’s role in an emergency situation in relation to other emergency team roles

- Refining the Emergency Plan checklists

- And identifying and assigning outstanding tasks

Emergency Planning Workshop: Teams and Roles

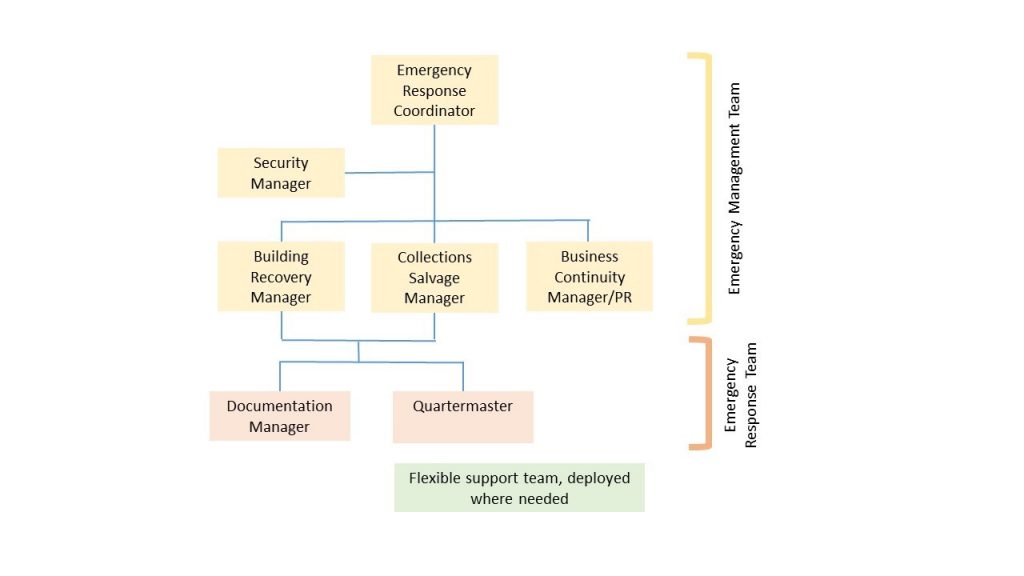

Our first task was to divide into our designated emergency team groups (I was part of the Collections Salvage Group). During an emergency, a wider Emergency Team with clear, designated roles will be activated and manage the incident (fig. 2). These sub-groups include the Emergency Management Team composed of the Emergency Response Coordinator, Security Manager, Building Recovery Manager, Collections Salvage Manager, and Business Continuity Manager/PR; and the Emergency Response Team, composed of the Documentation Manager and Quartermaster, with the addition of a Flexible Support team.

Provided with a series of paper slips with various tasks written on them, each team was instructed to gather the tasks of which their team had ownership and to clarify if others were required. For example, the Collections Salvage Manager’s main tasks are the protection and avoidance of damage to unaffected collections, the minimisation of future deterioration to the damaged material, and the prioritisation of damaged items for recovery. This was a beneficial and enlightening exercise as it clarified:

- What the central tasks within each team are

- Where tasks could either be shared between groups or where a single group should have ownership of a task

- Where teams could go to for support if a task is too large to tackle alone

Emergency Planning Workshop: Scenario

We were then presented with an emergency scenario (fig. 3). We needed to decide our actions and priorities, the equipment and resources required to enable us to perform our tasks effectively, how best to communicate and coordinate with other teams, and assess any requirements for specialist skills and training.

My group decided that the Collections Salvage Manager would:

- Manage the decant of objects to a safe location within a reasonable distance of the incident, but far enough away to ensure the safety of people and objects

- Assess the condition of collections and determine quickly which objects are damaged and those that should be prioritized

- Determine what sorts of salvage procedures are suitable

- Communicate regularly with curatorial and conservation advisors, and present clear instructions to the salvage teams

Emergency Planning Workshop: Outstanding Tasks

We concluded the meeting by discussing issues brought up during the course of the workshop, recorded by Rosie and Helena on sticky notes, and assigned to individual group members to examine further (fig. 4).

The workshop was beneficial in highlighting the importance of teamwork and shared responsibilities during a potentially chaotic situation. Emergency Planning manuals are not static: they are living documents, which are constantly revised. Continual re-evaluation ensures staff remain involved and have confidence in the Museum’s emergency procedures.

I enjoyed taking part in this workshop immensely and, thanks to the Fitzwilliam Museum staff’s passion and enthusiasm, the day was productive and inspiring.

Bibliography

Waller, R. (1994) ‘Conservation risk assessment: a strategy for managing resources for preventive conservation’, in Studies in Conservation, vol. 39, sup. 2, pg. 13.