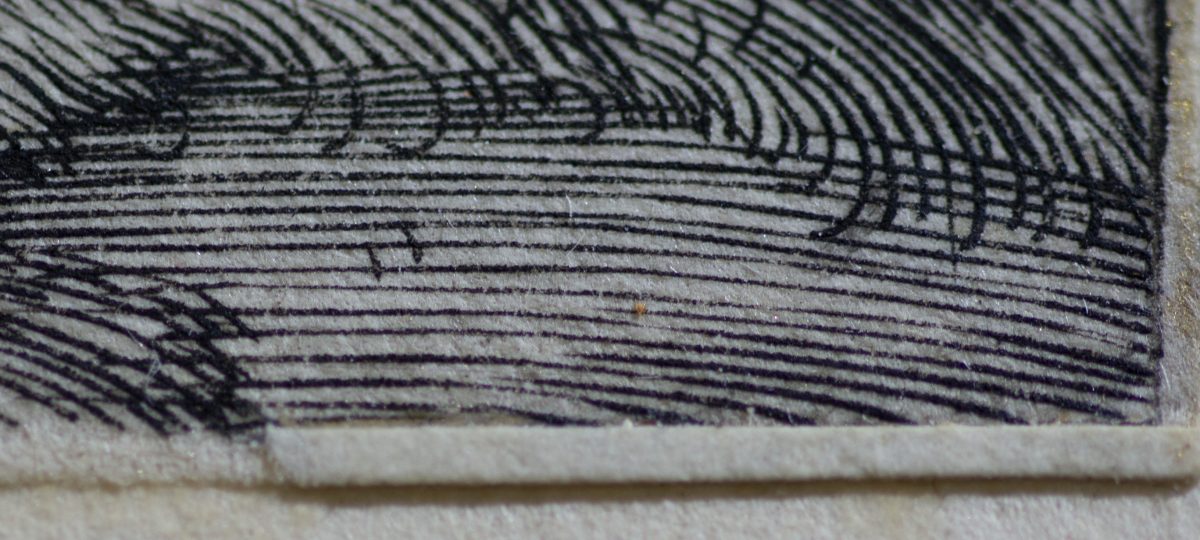

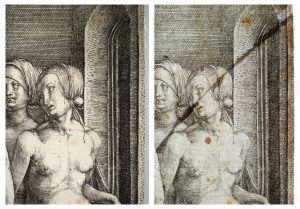

In a previous blog-post about the work I am undertaking on the collection of Dürer engravings at the Fitzwilliam Museum, I discussed the benefits of being able to compare a number of impressions of the same print. I also mentioned the historical practice of trimming sheets along, and sometimes within, the plate-mark. The latest batch of prints I have been working on contains two impressions of the print St Jerome in Penitence in the Wilderness (Fig. 1), which demonstrate this point.

Click on the image to enlarge.

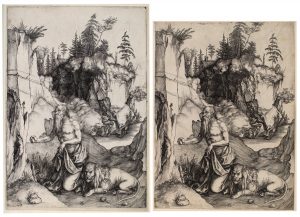

Both are rich, well-inked impressions of the same state1 of the print. When compared it becomes obvious that 22.I.3-65 has had a strip of approximately 15mm cut from the top edge, probably to remove an area of damage. This impression is also interesting because it has a number of tight, diagonal creases in the sheet, extending from the top right corner deep into the printed image (Fig.2). We can’t be certain what the cause was: it is possible that they occurred when the sheet of paper was formed, but I think they are more likely to be printer’s creases2. They have disrupted the printed image, and at some point, a rather crude attempt has been made to disguise them by retouching the areas that didn’t print properly with black ink.

Click on the image to enlarge.

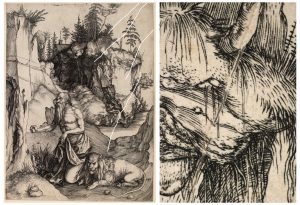

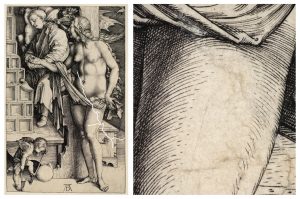

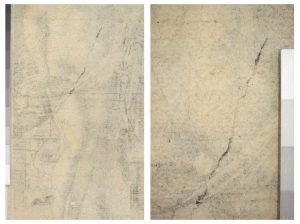

More care was taken to obscure a similar crease in the engraving The Four Witches (22.I.3-94). It is almost invisible to the naked eye, and was only revealed on the back of the sheet once it had been lifted from the mount (Fig.3). A restorer has applied very fine patches of paper to the front of the sheet, covering the area along the crease where the printing has been disrupted. The design was then carefully drawn in ink over the patches to match the surrounding image. This restoration becomes apparent when the sheet is viewed in transmitted light (Fig.4).

Click on the image to enlarge.

Click on the image to enlarge.

In this latest group of engravings there is another example of a very skilful repair which is really only visible under magnification. There is a complex tear to an impression of the print The Temptation of the Idler, also known as The Dream of the Doctor (22.I.3-103). The damage extends from the lower right edge of the sheet to the centre, through the standing figure of Venus at the right. It looks as though the restorer has had to pare the edge of the tear in places in order to achieve this near-invisible mend. When viewed from the back, these areas appear slightly darker as the printing ink is visible through the thinned paper fibres (Fig. 6).

Attitudes have changed and removal of original material, even very small amounts such as this, is not considered permissible in conservation today. But it is difficult not to marvel at these restorations: they clearly required huge skill and expertise.

During my treatment, I removed the lining paper from the print, and it was possible to wash the sheet carefully in order to reduce the discolouration without disturbing the tear. The print was then pressed, inlaid, and hinged into a new museum-board mount.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Another impression of this print (P.3104-R) was given to the Museum by Arthur W. Young in 1934. The old mount carries some more fascinating and revealing inscriptions from scholars that I described in my previous post. In this instance, the notes suggest that both Thomas Barlow and Campbell Dodgson considered this impression inferior to the ‘existing’ one discussed above, and it was therefore a possible candidate for disposal. But there is also a comment from J.W. Goodison who spotted the disguised tear, and this might be the reason that both impressions were fortunately kept3:

‘? Reject. This is a very fine, but your existing impression is also brilliant & I don’t think you need keep both. Existing impn. is clearer & this one has staining top corner v. on the other hand it has a much better margin than existing impn. T[homas] B[arlow] Aug 35’

‘I think this is hardly wanted C[ampbell] D[odgson]’

‘Wd suggest keeping this as existing impn. has a bad damage J.W.G[oodison]’

In Barlow and Dodgson’s defence, some of the tell-tale discolouration along the tear may not have been visible when they inspected it.

Looking closely at these very beautiful prints during the conservation process continues to reveal fascinating aspects of their history.

- In printmaking, a state is a different form of the image resulting from a deliberate and permanent change to the printing matrix – in the case of this engraving, a copper plate. Both of these impressions are the second (and final) state of the print. However, we know that 22.I.3-65 was printed slightly later as it has a small scratch to the mountains in the distance at the far-right edge of the image. This is not considered a different state as the mark is thought to be accidental.

- ‘[I]f the paper is too wet, it would distort, causing it to crease under the pressure in the printing press, forming a pleat, known as a ”printer’s crease”.’ Baynton-Williams (2009) The Art of the Printmaker: 1500-1860. London: A&C Black

- Jack Weatherburn Goodison (1903-1993), Assistant Keeper, Senior Keeper, then Deputy Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum until 1968

Tagged: Art on Paper, Conservation