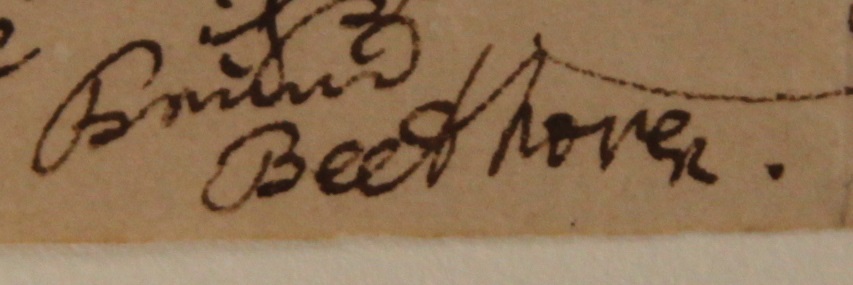

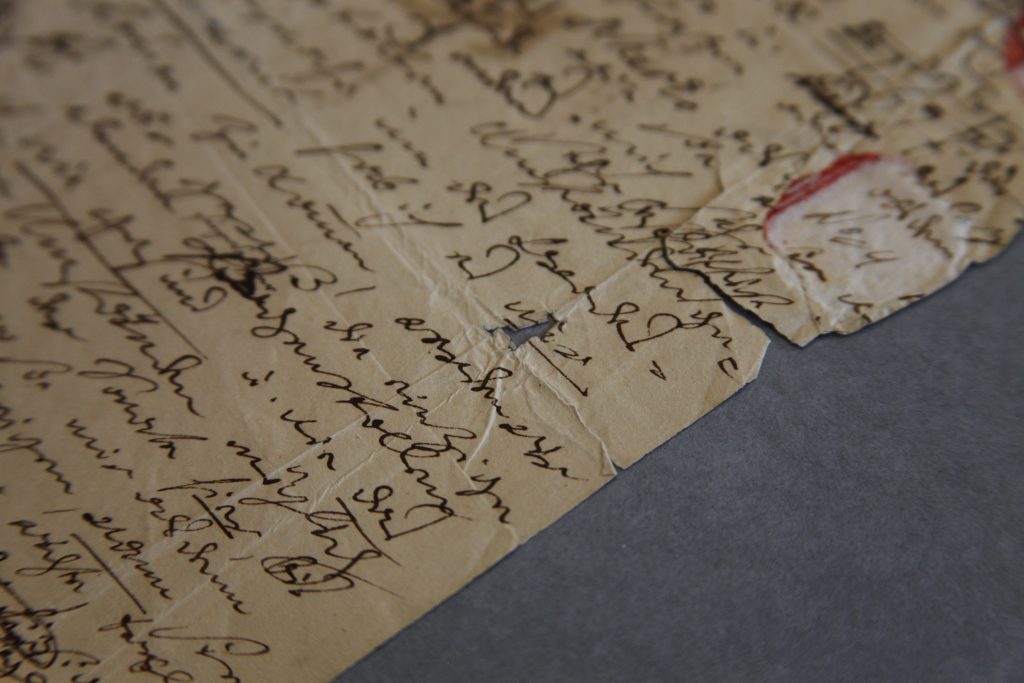

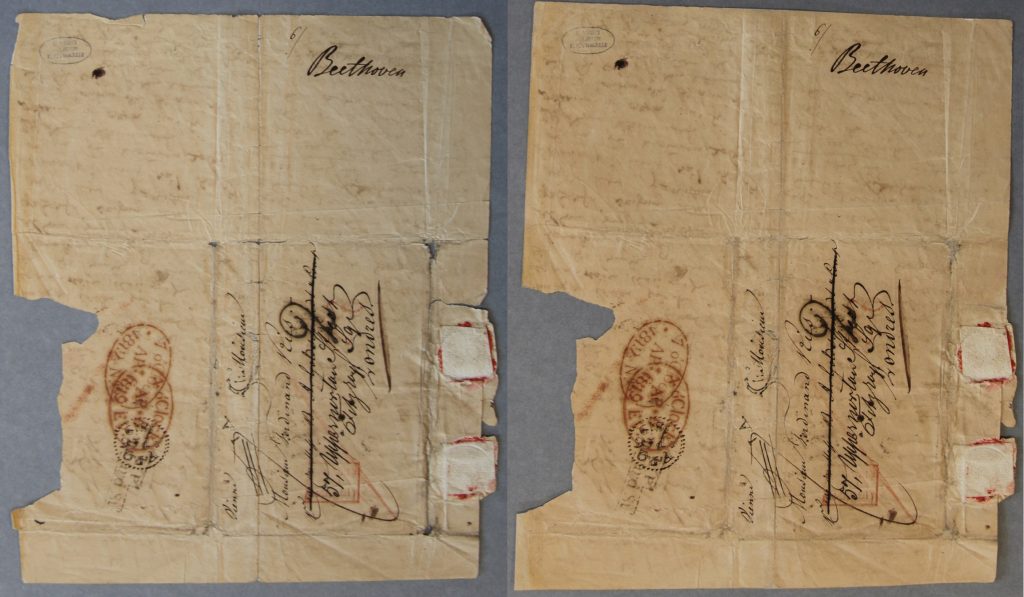

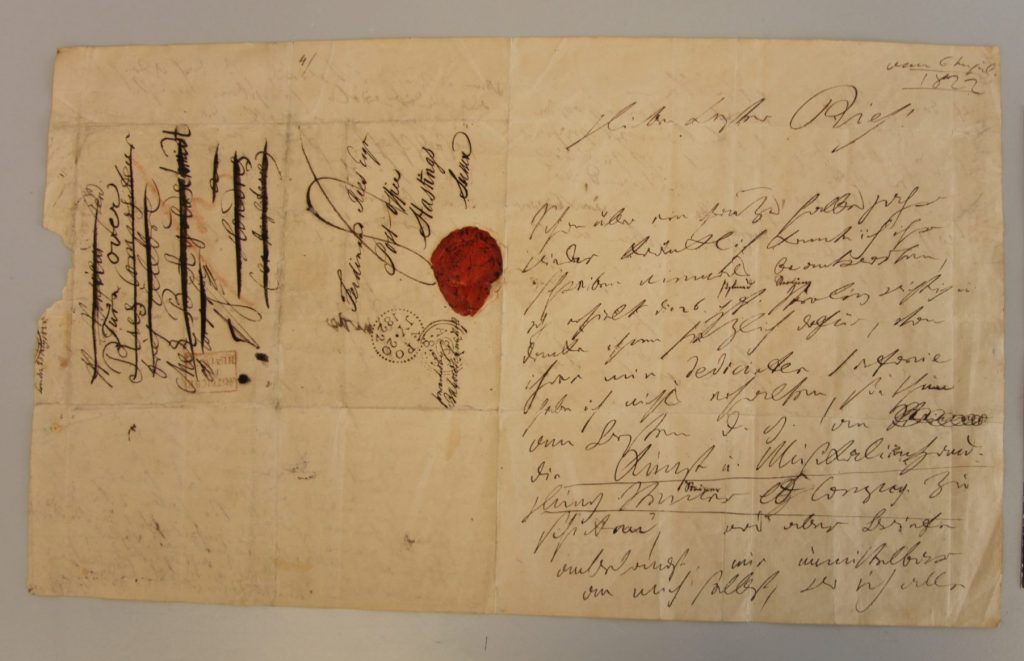

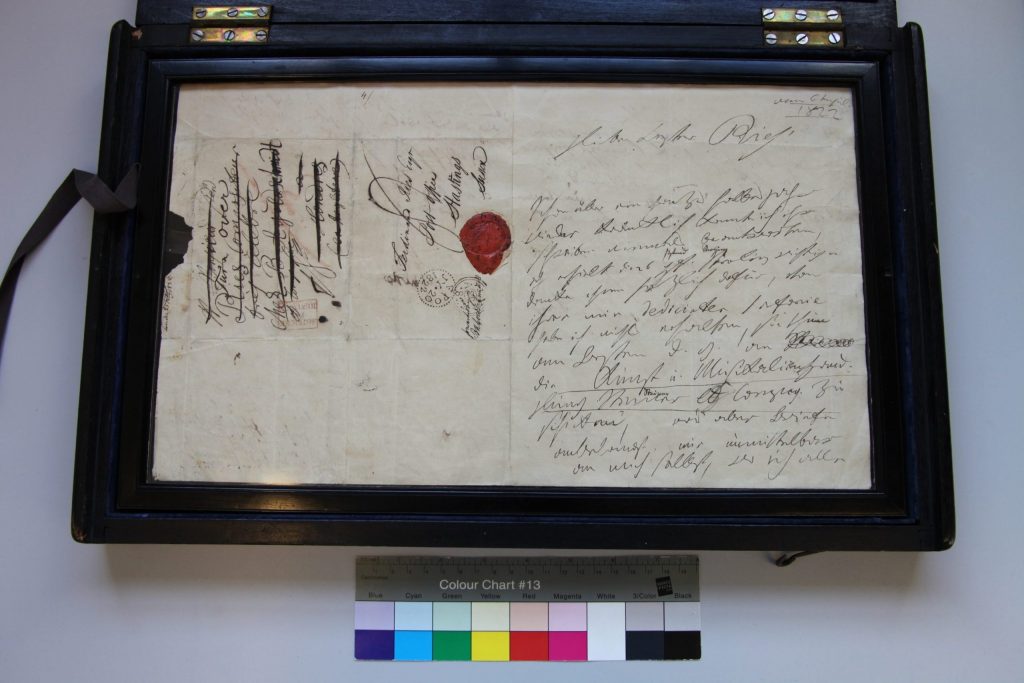

The manuscript conservators have been enjoying the chance to work on two autograph letters (i.e. documents in the composer’s handwriting) from Beethoven to his pupil and friend Ferdinand Ries in this, the 250th anniversary year of the composer’s birth. Both letters, dating from 1819 and 1822 respectively, are written with iron-gall ink on paper, and still show the creases and wax from when they were first folded up and sealed ready to be posted.

Conservation work was required to stabilise damage to the edges of the leaves and areas of loss where the corrosive ink had eaten through the paper support.

Repairs were carried out using tiny supports of fine (4gsm) Japanese paper coated with a remoistenable adhesive. This allowed us to minimise the amount of moisture we used whilst applying the repairs, an important consideration when dealing with manuscripts written in iron-gall ink.

Beethoven was a prolific correspondent and more than one thousand of his letters survive. The two examples to Ries in the Fitzwilliam Museum demonstrate the composer’s concerns around the business aspects of musical life: the need to make a living from publishing his works as widely as possible and the problems in getting them into print accurately. In the letter of March 1819, Beethoven writes that ‘it is hard to compose almost entirely for the sake of earning one’s daily bread.’ The letter of July 1822 demonstrates Beethoven’s concern to sell the Op. 110 and 111 piano sonatas (rather untruthfully described as ‘really not very difficult’!) to a London publisher for £26, but signals his intention to make a deal with a German publisher for the same material. At this time there was no copyright law to prevent the same composition being published simultaneously in different countries by different publishers, and the extra income from multiple sales was attractive.

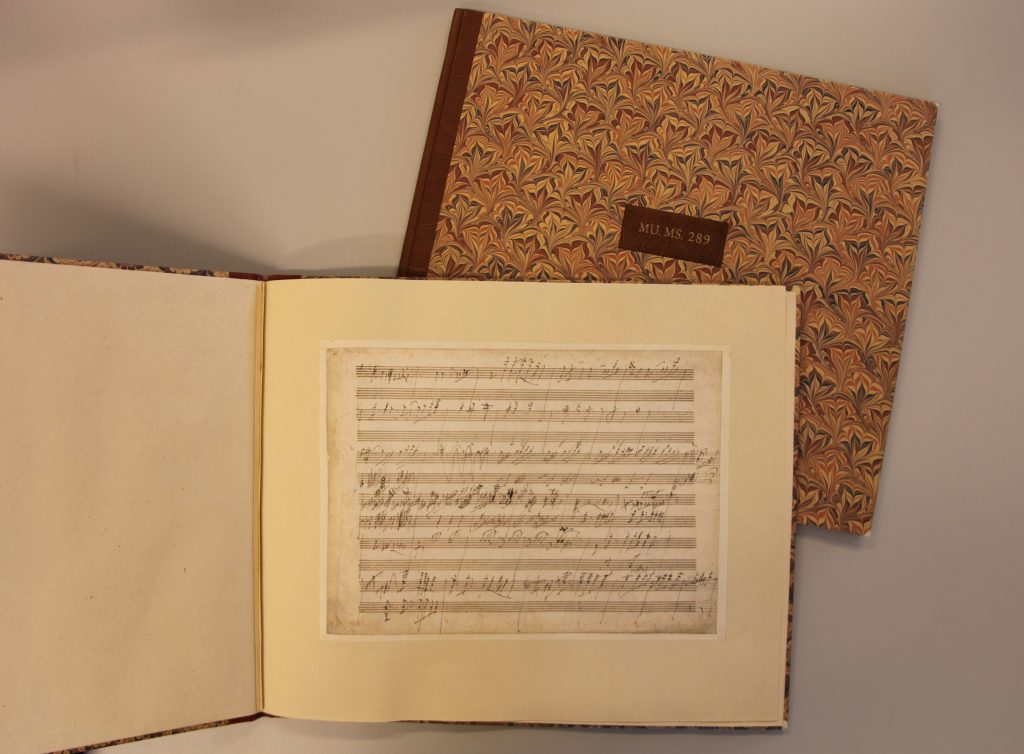

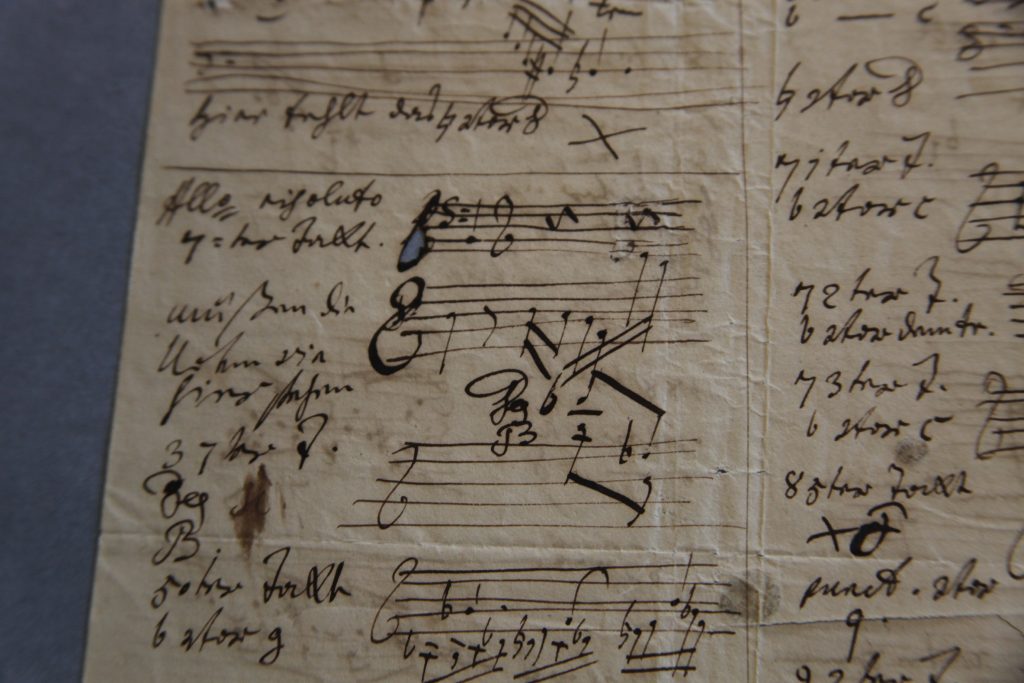

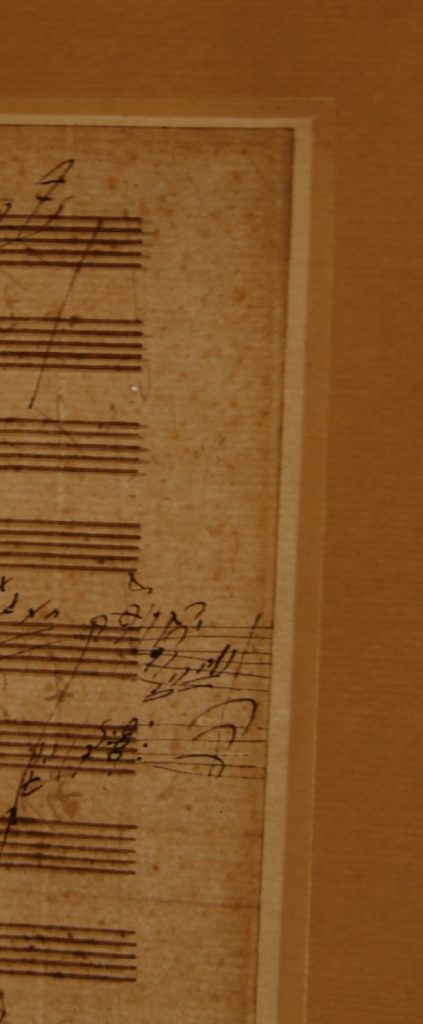

Beethoven autographs were sold off after the composer’s death and collected as souvenirs. Our collection also contains two leaves of autograph music manuscript by Beethoven, which were once part of the sketchbooks he kept to record his musical ideas. It is interesting to see how all these documents have been treated after Beethoven’s death, when they changed from being working texts or scores to mementos. The letter of 1822 was mounted between glass and framed, while the 1819 letter is only part of a much longer list of corrections Beethoven needed to have made to the London edition of the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata. (The other leaves are now in a collection in Germany.)

In more recent times, the music autographs were conserved by the famous Cockerell Bindery in Grantchester. The single leaves which were removed from the original sketchbooks soon after Beethoven’s death were mounted in larger sheets of paper to protect them from direct handling during use, then bound in two slim volumes covered with the instantly recognisable Cockerell marbled paper.

During our treatment, we were keen to maintain the ephemeral nature of the letters by making subtle repairs and providing good-quality archival folders for them, rather than mounting them permanently as leaves of a book.

Two of the autograph sketches, for the ‘Moonlight’ and ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonatas respectively, the two letters described here, and Beethoven’s life mask and pocket watch have just gone on display in Gallery 3 as part of the 250th anniversary celebrations.