How LEDs are now very much earning their keep

Gallery lighting – setting the scene

The best type of gallery lighting should be versatile, easy to calibrate, natural in appearance and ideally, environmentally compliant.

In recent years the advances in Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs)1 have been little short of extraordinary. This is now an established lighting technology and is ‘absolutely where the future lies’, no ifs, no buts.

Here at the Fitzwilliam Museum most of the lighting, along with many other heritage institutions and art galleries, is predominantly by halogen incandescent2 and to a lesser extent, fluorescent lamps. Although well-honed and now quite sophisticated, there are downfalls: significant energy usage, local heat production and certain reliability issues. Furthermore, when compared to LEDs, incandescent lamps have a pitiful lifespan and to compound matters, the sourcing of suitable parts has become increasingly difficult.

Replacing bulbs can be time consuming, disruptive, and in certain situations it is not always easy to undertake without an element of risk.

The average life expectancy of a traditional incandescent bulb will be around 5 years whereas by way of comparison, an LED will be closer to 100. These statistics alone reveal a startling disparity, and one that increasingly just cannot be ignored.

Recent advances in LEDs have seen a broader range of lenses available and perhaps of more significance, a greater accuracy with regard their colour rendition. So, when the cumulative power saving projections alone are taken into consideration, the argument against their implementation falls pretty much at the first hurdle.

Selection of LEDs

When selecting the type of LED for gallery use, four important factors should be considered carefully The colour rendition index, colour temperature, wavelength profile and light output or illuminance.

Diligent research and seeking guidance from an established supplier will pay dividends. See also: ‘LED Decision-Making In a Nutshell’ by James R. Druzik and Stefan W. Michaliski, August 2012, pp. 22, 23.

Colour Rendition Index (CRI)

The effect of a light source on colour appearance is expressed by the CRI index, on a scale of 0-100. Natural outdoor light has a CRI of 100 and is used by way of standard comparison.

CRI 60 – reasonable

CRI 70 – moderate

CRI 80 – good, reflecting colours ‘truly and naturally’

CRI 90 – excellent, a full and vibrant colour range (heritage organisations should be aiming for 90 plus).

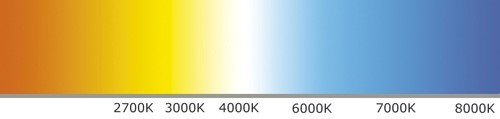

Colour temperature

The colour temperature of a lamp can be used to understand how the light will appear to the human eye. Measured in degrees Kelvin (K).

Both natural and emitted electrical light (various types) will be composed of different wavelengths. Light, from whatever the source, will have a unique profile and in turn a ‘specific colour temperature’.

Warm light 2,700 – 2,800 K

Neutral light 3,500 – 4,000 K

Cooler light 5,000 – 6,500 K (simulates daylight)

Daylight at noon is generally cited as being around 5,600 K. However, in reality this figure will vary according to both the time of day and weather.

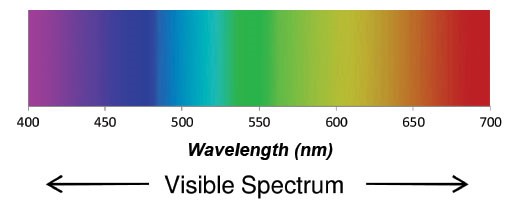

Wavelengths

Measured in nanometres (nm)

Ultra-violet3 (UV) light waves fall below 400 nm and is invisible to the human eye. The lower the wavelength, the higher the frequency and potentially, more damaging to museum collections. UV should be excluded wherever possible.

By contrast, Infrared4 radiation is above around 750 nm at the higher end of the scale and will produce heat. Heat speeds up chemical reactions and this becomes relevant when caring for collections with regard the rates of decay and degradation.

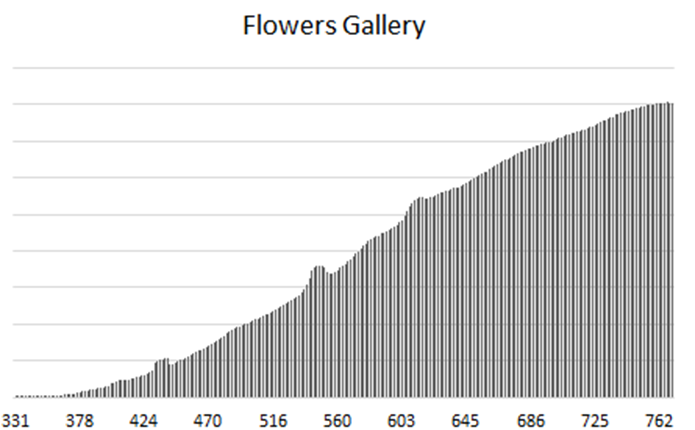

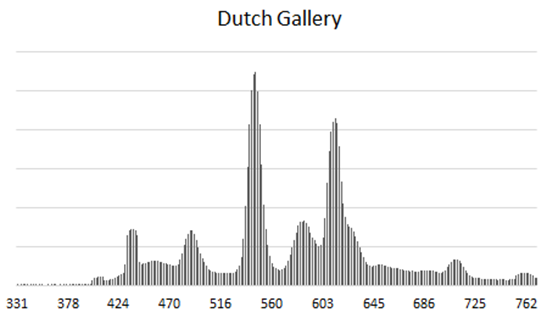

The graphs below compare old incandescent lighting in the Flowers Gallery with newer LED lighting in the recently refurbished Dutch Gallery.

Correlated Colour Temperature: 2750 K

Colour Peak: 766.77 nm

Lighting: Incandescent lamps (Halogen) and some filtered daylight

Correlated Colour Temperature: 3761 K

Colour Peak: 545.82 nm

Lighting: LED (predominant gallery light source)

Skylights: Fluorescent tubes minimal filtered daylight

Wavelength profiles captured with a Spectrometer (GL Optic’s GL SPECTIS 1.0 touch) January 2017.

Light Output – Illuminance

Measured in Lux5

The illuminance considered appropriate for most gallery spaces will be dictated by both addressing audience need and the various sensitivities of the collections displayed (the material type, make-up and overall condition).

Taking a light reading6 in the Dutch Gallery. Oil on panel (detail) by Abraham van Calraet, 1642-1722.

Light levels and exposure should be carefully monitored and ideally logged, since light damage to museum objects is often subtle; the effects are cumulative and crucially, any change inflicted is irreversible.

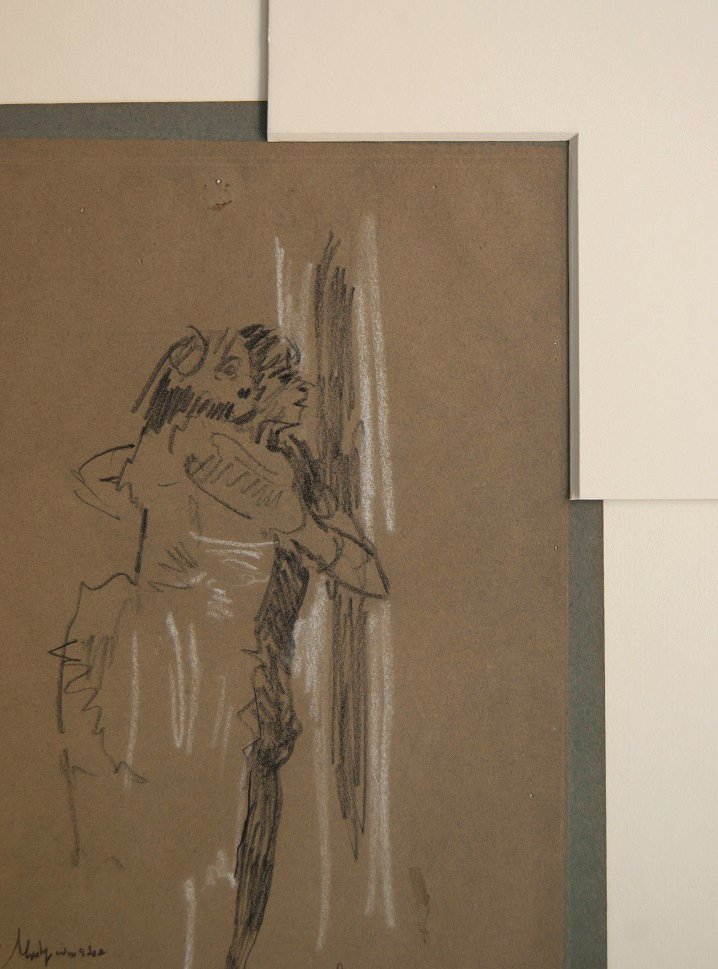

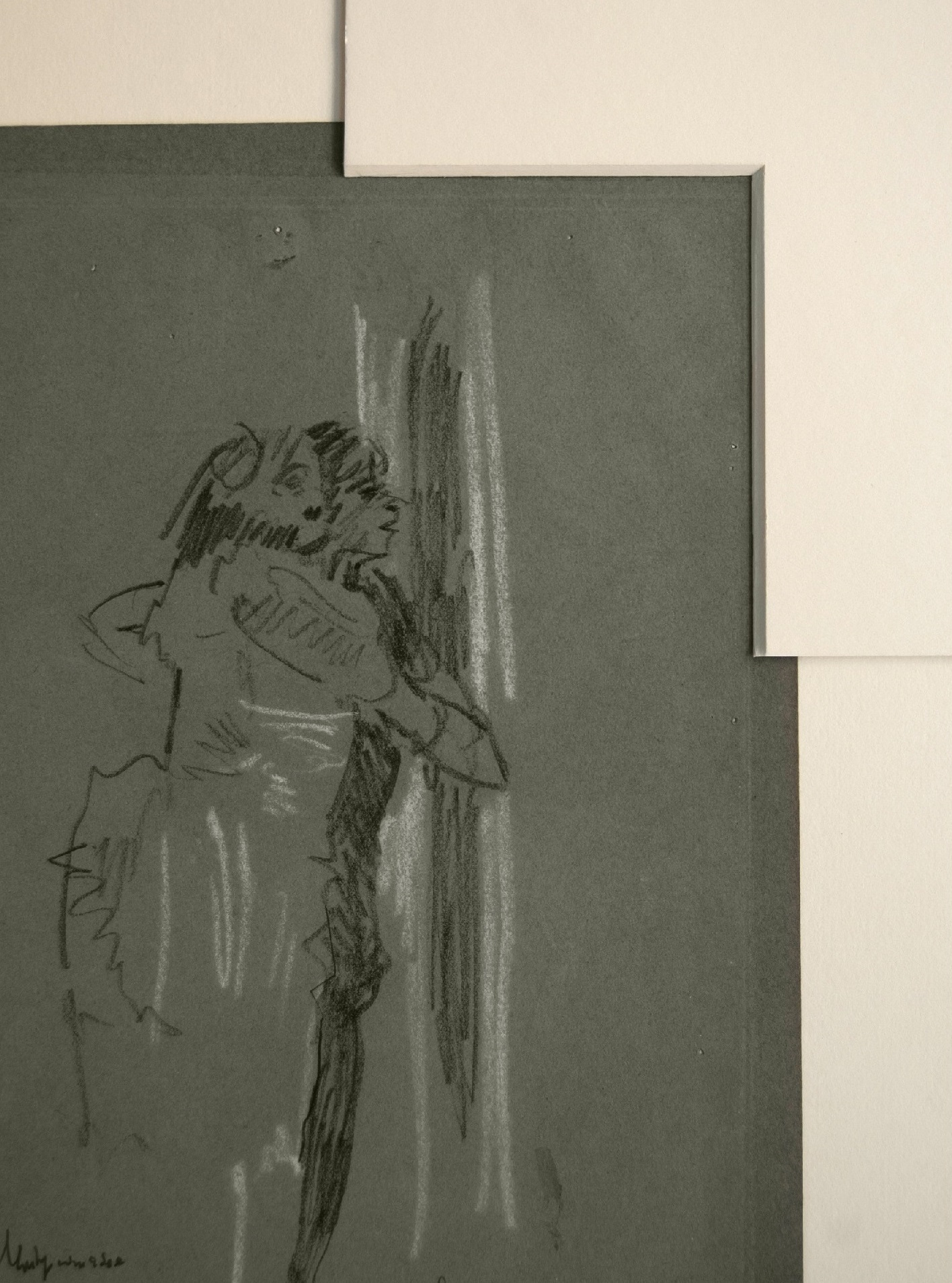

By way of an example see the drawing below where the cut away top mount shows just how drastic the change can be.

Black and white chalk drawing on a coloured paper by Walter Sickert, 1860-1942 (detail).

In this particular case, the coloured paper support was originally and entirely, a greenish blue. The colour shift from green to brown, where the drawing has been exposed to light, alters both the look and quite possibly, the intended context. Fortunately, such extreme examples are rare within museums and as conservators, we always endeavour to keep it this way.

A computer generated overlay gives an impression of how this drawing would have originally looked.

Intelligent lighting design: Creating a sense of theatre

With carefully calibrated light levels, directional beams and consideration to the colour balance (within the range of whites) the impact of intelligent lighting can be little short of ‘transformative’. As such, many of the more informed galleries are now making good use of specialist lighting designers.

An example of exhibition lighting here at the Fitzwilliam Museum:

Degas: A Passion for perfection (2017).

Wall mounted art works and a cased table top display, carefully lit.

Wall mounted art works and a cased table top display, carefully lit.

Bronze Spanish Dancer (foreground), posthumous cast, by Edgar Degas.

Bronze Spanish Dancer (foreground), posthumous cast, by Edgar Degas.

In the above two examples both the needs of the museum objects and the overall gallery lighting has been planned.

The recently refurbished Dutch Gallery (2014)

As part of a recent refurbishment project in one of the galleries here at the Fitzwilliam Museum, various lighting modifications were considered. The museum adapted – it embraced change and now this particular gallery is predominantly LED lit.

The Dutch Gallery with a c1690-1700 Flower Vase (foreground) hosting, in this case, some convincing silk flowers. 7

Displaying a mixture of museum items within the same gallery space can present certain challenges since each item type will have a different tolerance.

As such, the most sensitive object will tend to dictate the parameters. In this particular gallery the light levels falling on the displays range between 80 – 130 Lux (UV excluded) and are fully compliant with current standards.

The Dutch Gallery (above) is a wonderful example of just how beautiful a space can become with careful consideration and resourcefulness. LED’s are now very much part of the conversation and with regard to a transition, it is not a question of if but when. For my money – the sooner the better.

Seeing things in a new light – how LEDs are now very much earning their keep. Part 2 will follow in the coming months. Various pieces of studio equipment making use of LEDs will be further investigated and discussed.

Further reading

The Museum Environment, (second edition), Gary Thomson, ISBN 978-0-7506-2041-3 Butterworth-Heinemann

Lighting for the built environment LG8: Lighting for museums and art galleries (The Society of Light and Lighting) ISBN 978-1-906846-7

Guidelines for Selecting Solid-State Lighting for Museums, James R. Druzik and Stefan W. Michalski, August 2012 (Canadian Conservation Institute & The Getty Conservation Institute) pp 22, 23 ‘LED Decision-Making In a Nutshell’

Lighting Industry Liaison Group, A guide to the specification of LED lighting products, 2012

Thanks go to my many kind colleagues, including the photographic team here at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Helena Rodwell in Collections Care and to Richard Carpenter, our PDP Technician, for quite literally giving me a hand (his right hand in ‘taking a light reading’). Lastly, to Gwendoline Lemée, for her invaluable guidance and ever cheerful encouragement.

- Light Emitting Diode (LED) a semiconductor crystal that emits light when a voltage is applied. Solid State Lighting is a more general term for both LED and OLED (organic flexible) technology. The majority of LEDs do not emit heat.

- Incandescent lamps, in a variety of forms, halogen, tungsten and so forth work by the process of incandescence. Light is emitted as a result of an electrical current heating a metal filament. Incandescent lamps are now considered to be among the least energy efficient of all forms of electric lighting.

- Ultraviolet (UV): wave lengths of 10- 400 nm (below the visible spectrum). The Ultraviolet element of light is measured in microwatts of UV radiation per lumen. As a general rule, any source light emitting more than 75 microwatts per lumen should be filtered. Filters can be applied at source (light lenses or applied films) or locally, by way of specialist picture glazing.

- Infrared radiation is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with longer wavelengths than those of visible light, and is therefore invisible to the human eye.

- Lux (lx) the ‘standard international’ unit of illuminance, equal to one lumen per square metre. This figure is used to rate light output.

Lux levels, within a museum context, is the brightness of light or more specifically, the actual amount falling on a specific surface.

Light levels below 50 lux are generally recommended for objects sensitive to light such as textiles, watercolours (including coloured papers), manuscripts and most natural history exhibits. 200 lux is considered acceptable for most oil paintings. - Using an Elsec 764 UV + Monitor (one of several types currently used at the Fitzwilliam Museum). It is important to have light meters regularly re calibrated and perhaps, helpful to occasionally compare different light meters against the same light source, by way of comparison. Although some light meters are believed to be less reliable whilst taking Lux readings from LEDs the various product manufacturers should be able to give the reassurance required or otherwise.

- Fresh flowers can bring in a wide variety of unwanted pests and insects and as such, they are not generally recommended within museum or heritage settings. Supplier of silk flowers: Fake Landscapes (the artificial plant company), Fulham Road, London.

Tagged: Gallery Lighting, LED, Light Damage, Light Levels