Every now and again, an upcoming exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum provides a welcome opportunity to carry out much needed conservation treatment on important works from the Museum’s collection of paintings. While these works may in fact normally be on display in the permanent galleries, and their general state of preservation is stable and acceptable, they have not necessarily received further attention from the Museum’s conservators since they came into the collection many years ago.

Paintings sitting in the same spot on a gallery wall year after year are not usually scrutinised in the same way as works emerging into the light after a long period in storage. It is often a challenge to find the time and opportunity to look at something very familiar with fresh eyes! However, for each of the five paintings that were given a session of careful TLC by staff and students at The Hamilton Kerr Institute before entering this special exhibition, the visual changes resulting from the treatments were more drastic than initially anticipated. While the size, style and colour scheme in these works are in one sense quite different, they are also all depictions of tender moments between the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, painted to serve as devotional pieces for private worshippers in the 15th and 16th centuries. The removal of discoloured varnish layers, mismatched overpaint and centuries of dirt, transformed the images and revealed paintings of even greater colouristic beauty and refinement than could be appreciated previously.

The small Virgin and Child, tentatively attributed to Pietro di Niccolo da Orvieto (c.1430-84) although its iconography and decorative elements could suggest a considerably earlier date, has always been on display showing only its front. When it was recently taken off the wall for a closer assessment however, it became evident that the back is also well worth looking at. Just like the front, the back was originally prepared with a smooth, white gesso ground. A convincing trompe l’oeil frame was then painted to surround an image that was initially very hard to make out through the thick dirt layer that has accumulated through the centuries. As cleaning progressed, a brilliantly colourful, fictive marble slab emerged (figure 1).

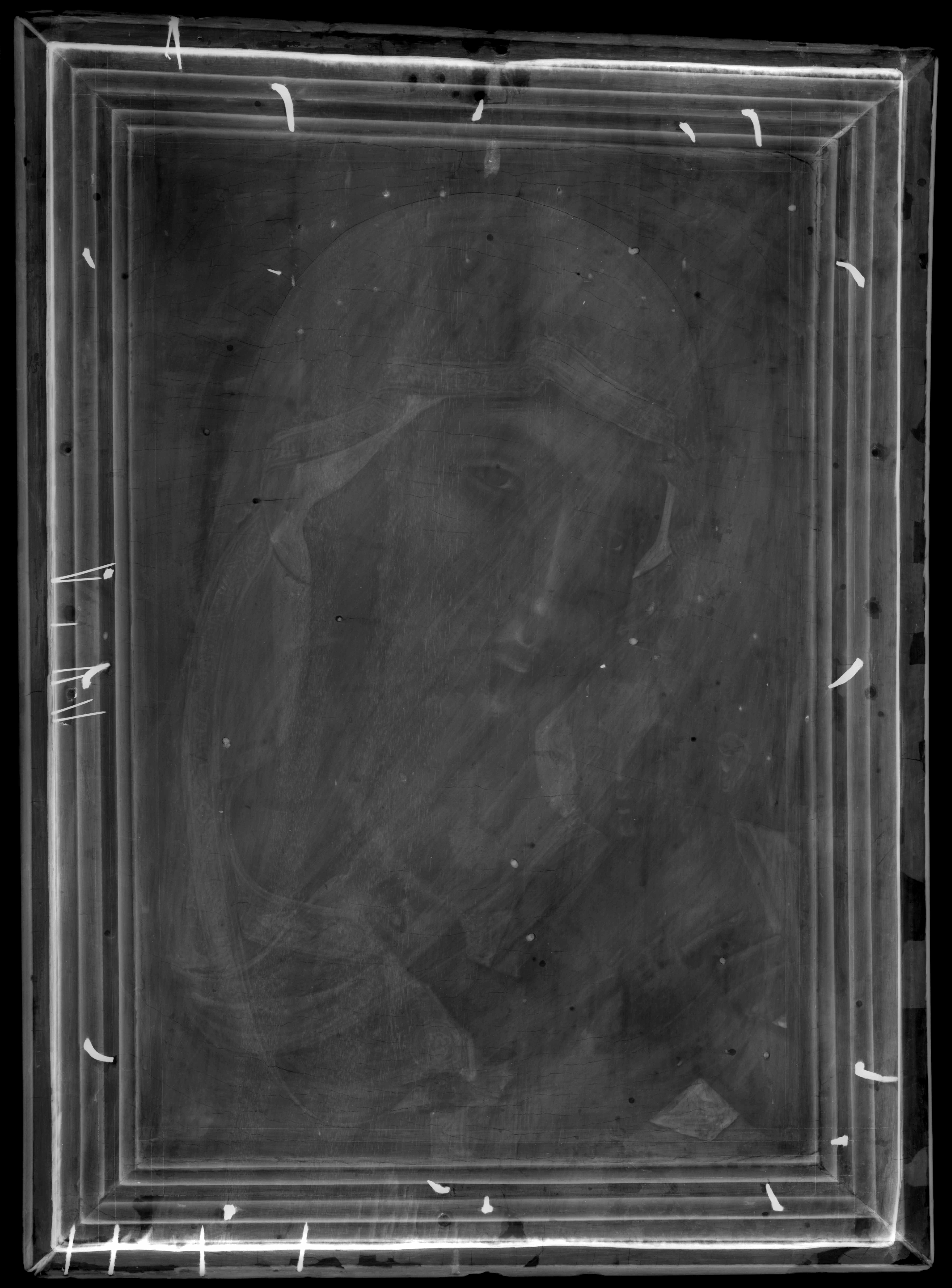

The panel was subjected to x-radiography, which revealed how the timber structure was put together prior to the gesso application (figure 2). Four individual moulding profiles were nailed to the face of the panel with three to four nails along each side, which were bent to lie flush with the back prior to the gesso application, thus sealing them within the structure.

Although the front of the panel was also somewhat obscured by dirt and varnish, it had clearly been cleaned at least once in the past. Remarkably, most of the decorative scheme is still in rather good condition.

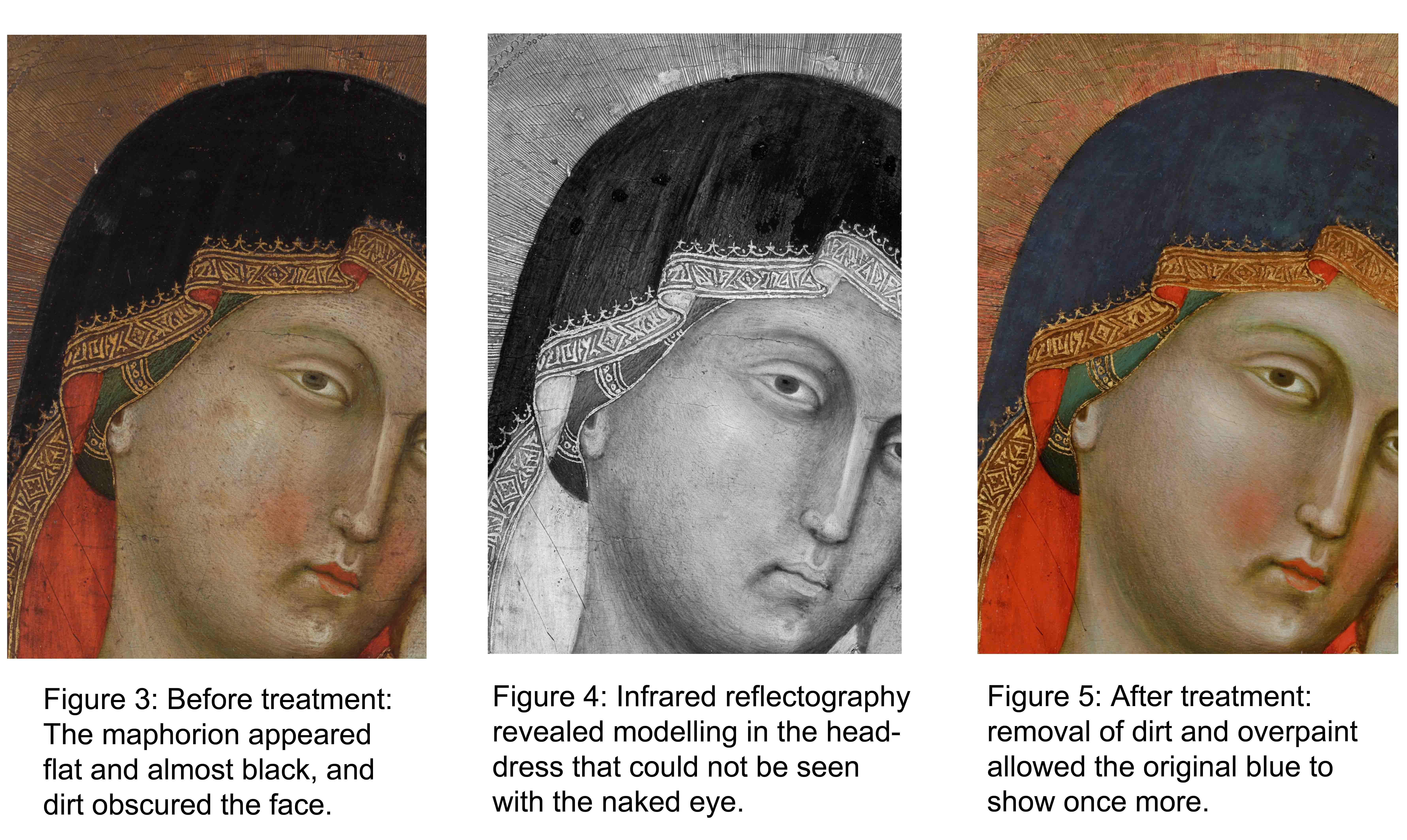

Even though the painting’s style owes much to the stylised and somewhat flattened depictions of the Madonna and Child in the Byzantine icon tradition, the Virgin’s outer garment, the maphorion, was still surprisingly dark and flat compared to the other passages in the painting (figure 3). However, infrared reflectography showed how folds were in fact present in the maphorion (figure 4). Dark overpaint obscured these folds to the naked eye, and careful removal of this non-original layer revealed the original, but worn, blue colour of the garment, painted with two paint layers containing the blue mineral pigment, azurite (figure 5). The top layer has rather large pigment particles, which would have resulted in a rich, velvety surface. Good quality azurite was deliberately employed coarsely ground, because with further grinding, it loses its intensity of colour and turns increasingly grey. The gritty surface resulting from the use of a coarse pigment would have rendered it vulnerable to wear and absorbent to later applications of medium and overpaint, leading to the darkening effect that gives the misleading impression of a black paint passage.

As a result of careful cleaning and a changed approach to display, the beauty of both front and back of this small, devotional object can once again be appreciated in the current exhibition, where it sits in a vitrine allowing both sides to be seen.

Seven painting conservators spent nearly 600 hours on careful conservation and restoration work up to the ‘Madonnas and Miracles: Private Devotion in Renaissance Italy’ exhibition, and if these madonnas have indeed become familiar faces on the walls of the Museum’s permanent collection, they are certainly well worth a second glance, restaged alongside other devotional objects for the duration of the show, which runs from March 7th to June 4th.

To read about the conservation work and painting techniques of the School of Botticelli tondo and of the Joos van Cleve Virgin and Child, follow this link to the Hamilton Kerr Institute Student and Intern Conservation Blog, where you can also read about the challenging process of creating a reconstruction of the Virgin and Child discussed above, using traditional artists’ materials and techniques: https://hamiltonkerrinstitute.wordpress.com/

All images in this post are the copyright of The Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge

Save

Tagged: Conservation, Madonna and Child, Madonnas and Miracles, Paintings, Restoration