For anyone working on the topic of early modern portrait miniatures, 2019 was an exciting year, seeing the fruition of much new research in exhibitions and publications, including the large exhibition Elizabethan Treasures: Miniatures by Hilliard and Oliver (21 Feb 2019 – 19 May 2019), which introduced a new generation to this art form at the National Portrait Gallery, London; Elizabeth Goldring’s much-awaited biography, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist, (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2019); and Cambridge’s very own focused display, Secrets of a Silent Miniaturist: Technical Analysis of Isaac Oliver’s Miniatures at the Fitzwilliam Museum. In Cambridge, work on miniatures continues with the technical analysis of Oliver’s work and, as part of this project, the digitisation of the hitherto largely unexplored archive of Jim Murrell (1934–1994), housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute (HKI).

Vernon James Murrell, known as Jim, was a conservator of miniatures and wax objects at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (V&A) from 1961 until his retirement in 1994. Murrell worked on the V&A’s National Collection of portrait miniatures as well as examples in private and other public international collections. He wrote and contributed towards a number of key publications, in which he shared his technical knowledge of miniatures. These include John Murdoch et al., The English Miniature (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1981); Roy Strong and V. J. Murrell, Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered, 1520–1620 (London: V&A, 1983); and The Way Howe to Lymne: Tudor Miniatures Observed (London: V&A, 1983). His edition of Edward Norgate’s seventeenth-century treatise Miniatura, or The Art of Limning, co-authored with Jeffrey M. Muller, was published posthumously (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1997). Murrell’s work pioneered the technical study of miniatures and the communication of his findings to non-specialist audiences, and continues to be used today by art historians and new audiences.

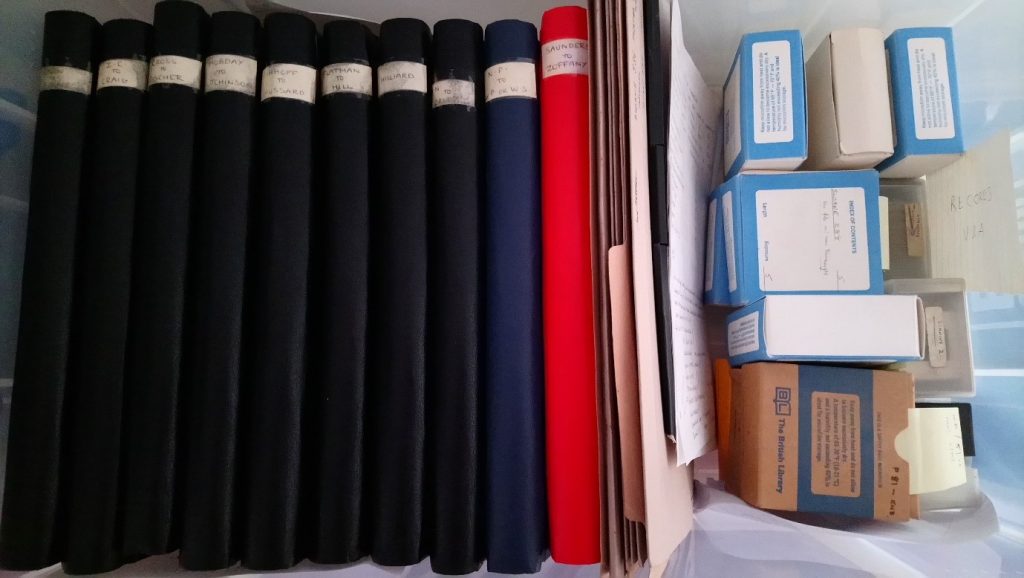

The archive contains Murrell’s notes, sketches, slides, and lectures, most of which have not yet been published, as well as secondary reading materials.It reveals adesire to understand how miniatures were made, the materials and techniques which were used to create them, and Murrell’s curiosity concerning the technical interest in miniatures in early modern Britain. His notes reveal how artists created miniatures, what pigments were employed for the paints, and how the artist applied the paint to the support. Murrell transcribed copies of historical manuscripts and annotated them to indicate where recipes were unique, had been copied from other treatises, and where they offered a variation on existing knowledge. These annotations highlight the ways in which information circulated amongst artists, patrons and other interested readers in early modern England. Information about the painting of portrait miniatures can also be found within a variety of written materials on other topics, including commonplace books, books of coats of arms and heraldry, and books on plants.

The archive was donated to the HKI by Jim’s wife, Ann Murrell Ballantyne, a restorer of medieval wall paintings, in June 1999. Access to the archive is currently greatly limited but plans are afoot to create an archive centre at the HKI. In the meantime, however, and for those who are not able to travel to the HKI, it is hoped that the digitised version will soon be available online, providing access to reproductions of Murrell’s notes and sketches.1

Between April and December 2019, I digitised over five thousand images from the archive. The images were captured using DocScan, a free mobile phone scanning app which was installed on a Sony Xperia XA1. Docscan works with the mobile camera and does not require a flatbed scanner. This would make it a good option for researchers visiting archives where no scanner is available or where scanning may damage the original. Often, the DocScan app could detect the outlines of a page and suggested where to crop and edit the images before saving to the phone. I found that this function worked better with pages of typed text than with notebooks of faint, pencilled sketches or notes. Once the images had been captured and edited, they were saved as PDF files and transferred to a computer. This made it easier to view the image to check for focus and cropping. Sometimes images needed to be taken again to ensure legibility, which was the main priority of this project. Digitising the archive will not only increase accessibility, but also help decipher Murrell’s notes: his script is tidy but sometimes very small, and is therefore easier to read once it has been magnified on the computer. Digitisation will also help to ensure the longevity of Murrell’s knowledge, should anything ever happen to damage the original material.

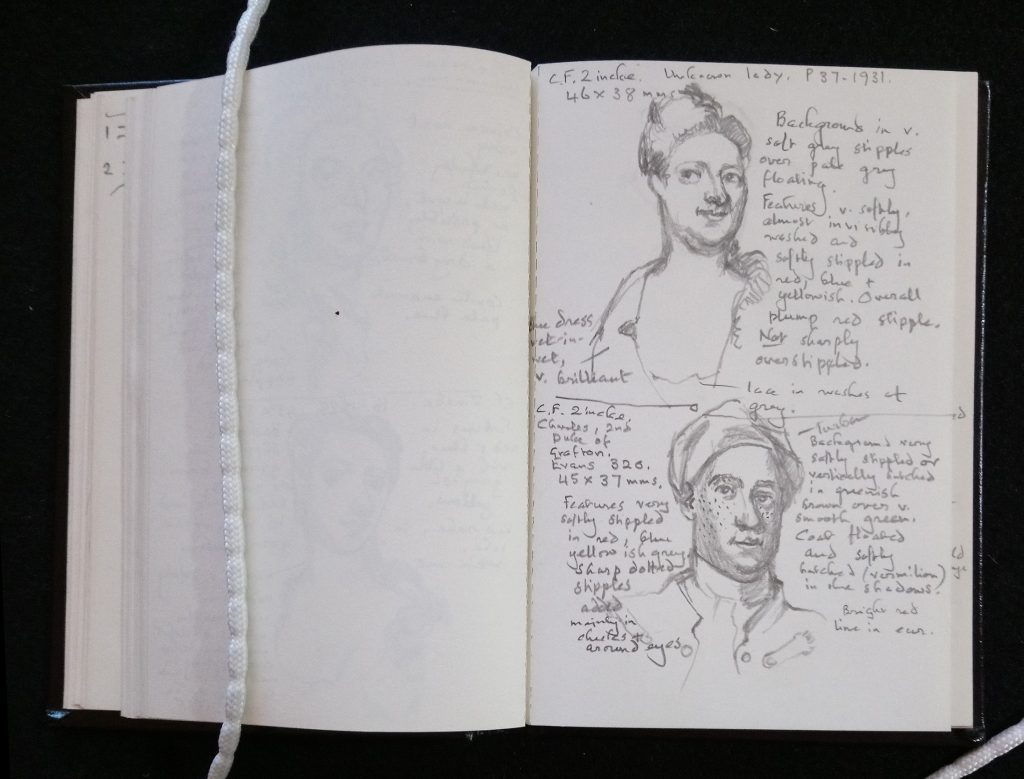

The image above shows a digitised page from one of Murrell’s notebooks in which he has included notes and sketches from the V&A collection of portrait miniatures. The upper image shows Murrell’s sketch of an unknown lady painted by the enamel miniature artist, Christian Friedrich Zincke, c. 1705–1745, 46 mm x 38 mm (P.37-1931). With the benefit of viewing the original painting under magnification combined with his technical knowledge of how these works were created, Murrell has noted that the sitter’s blue dress was painted ‘wet-in-wet’, a painting technique in which paint layers are applied one after the other, before the previous layerhas dried. This technique is used to create a very smooth appearance with no visible brushstrokes. Murrell also noted this highly finished effect in the pale grey ‘floating’ background of the miniature, and the almost invisible washes laid down to create the features of the figure. Below this in Murrell’s notebook is a sketch of a second miniature by Zincke: Charles, 2nd Duke of Grafton, c. 1730, enamel on metal, 45 mm x 37 mm (Evans 320). Again, Murrell’s close observation of the work reveals the techniques whereby Zincke achieved his smooth effects. The background is noted as ‘very softly stippled’,a technique of using small dots or short strokes of the paintbrushwhereas vertical hatching (closely drawn lines) and ‘sharp dotted stipples’ are used by the painter to model the sitter’s face. The different sorts of marks are clearly represented in Murrell’s sketch. The notebook contains further sketches and notes on miniatures by Zincke and his contemporaries.

The archive now exists in its original state and, largely, as a series of digitised files. With further funding, it will be possible to make these digitised files available for public viewing online. It is hoped that providing the Murrell archive with an online presence will provide an ongoing legacy and foster the revival of interest in miniatures. The funding for the digitisation work undertaken so far was granted by the British Academy Small Research Grant scheme and the Fitzwilliam Museum’s Marlay Group, as part of an ongoing technical research project on Isaac Oliver.

If you want to know more or contribute to the project, please get in touch by emailing portraitminiatures@fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk.

Bibliography

DocScan http://docscan.ifunplay.com/

Elizabeth Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist, (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2019)

Jeffrey M. Muller and Jim Murrell, Edward Norgate: Miniatura, or, the Art of Limning (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1997)

Jim Murrell, The Way Howe to Lymne: Tudor Miniatures Observed (London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983)

Roy Strong and V. J. Murrell, Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered, 1520–1620 (London: V&A, 1983)

John Murdoch, Jim Murrell, Patrick J. Noon and Roy Strong, The English Miniature (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1981)